Political discussion should never come down to ‘owning the libs’

We are a people increasingly unlikely to extend the assumption of good faith to anyone across from us on the political divide.

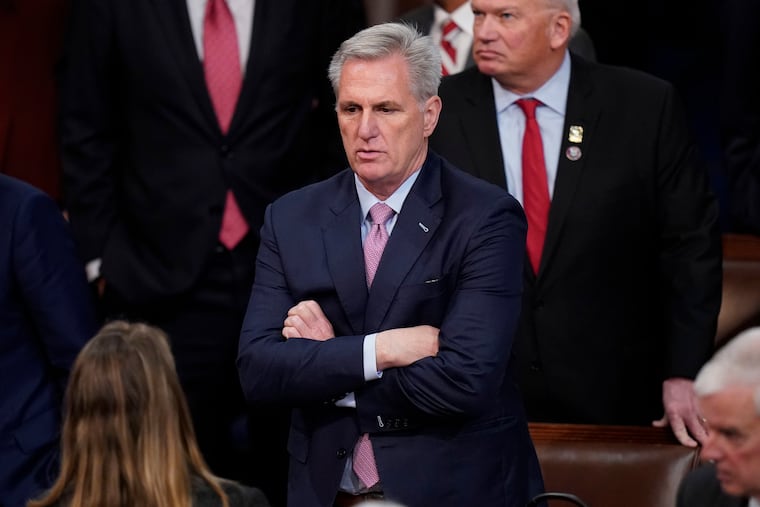

The fight for the speaker’s gavel in the U.S. House of Representatives has captured the nation’s attention as yet another example of politicians who refuse to bend an inch or trust the “other side” one bit. Contrast that with what happened in Harrisburg.

Facing an even more closely divided chamber and a majority sure to shift at least once in the next session, a few Republicans joined Democrats in electing Mark Rozzi, a Berks County Democrat-turned-independent, as speaker. The compromise settled several brewing fights and may lead to more stability over the next two years — along with the possibility of actually passing some legislation.

This is worthy of praise, especially since reaching across the aisle — or even meeting in the middle — is more and more rare in our modern politics. The blame for this, however, does not lie only with the professional politicians: Their values and practices reflect the voters’ own habits. And we are a people increasingly unlikely to extend the assumption of good faith to anyone across from us on the political divide.

» READ MORE: America is over: Let’s just split into different countries | Opinion

The habit arises from tribalism and is an easy one to fall into. When someone you already disagree with does something you think is underhanded or dishonest, it is simple — and correct — to condemn it. But after a while, our minds unconsciously start to make the leap from “there are some bad folks on the other side” to “all the folks on the other side are bad.” We know (or should know) that doing this along the lines of religion, race, or national origin is bad. But when it comes to political partisanship, we fail to avoid that age-old trap.

Social media adds to the problem by awarding likes and shares to posts that pillory the opposition with savage one-liners. Rage begets clicks, while nuance and thoughtfulness are ignored.

That deep distrust can come to replace actual ideas in our discourse, making “owning the libs” (or its left-wing equivalent) into the highest good in partisans’ minds. That’s not good for America, and it’s not going to help anyone get anything done. Assuming bad faith from someone you disagree with is poisonous to conversation and kills the chance of finding a solution to any issue on which people are closely divided.

A fairly minor example: In my last column, I suggested that Philadelphia use ranked choice voting in the next Democratic mayoral primary. Ranked choice voting is not an explicitly left- or right-wing position, though it is more popular on the left. So, a conservative columnist suggesting a left-coded idea should seem like a centrist view people would like, right?

Of course not. Instead, some partisans assumed I proposed this to somehow advantage Republicans (although how exactly that would work in a Democratic primary is still unclear to me). Now, I don’t mind letters from readers criticizing me — it is a part of the job and a part of healthy public discourse — but this kind of criticism makes no sense except to someone who always assumes bad faith by “the opposition.” It advances no goal or principle — it only says, “If someone from that faction is for it, I must be against it.”

To be clear, there is a set of galaxy-brained political pundits who will always talk about compromise first, as though the median, moderate position is not only possible but is also the best and highest good. That is not what I’m saying. It’s good to have principles and to stick to them.

» READ MORE: Josh Shapiro ran like a moderate. He should govern like one, too.

But it’s also good for your opponents to have principles, and we should not assume that them sticking to their principles is evidence of an evil, underhanded plot to destroy America. Sometimes, people have good-faith disagreements. Differences of opinion are not necessarily cause for all-out partisan warfare.

We used to hear this sort of sentiment all the time from people such as George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and John McCain. We rarely (if ever) hear it from Donald Trump or Joe Biden, nor from Doug Mastriano or John Fetterman.

Can we disagree without assuming bad faith? Even online? Rebuilding trust requires the radical departure of assuming people act in good faith until they prove otherwise. One place on the internet that practices this is Wikipedia. Editors on that site get into serious disputes over the most minor details of an article, but the principle “assume good faith” is one of the site’s core tenets.

That does not mean you have to agree with other editors there, only that you should go into a dispute thinking that “people are not deliberately trying to hurt Wikipedia, even when their actions are harmful. Most people try to help the project, not hurt it.” We should extend that assumption to our state legislature: Most legislators want to help Pennsylvania, not hurt it. The same goes for Congress.

That may sound hopelessly naive, but assuming the best does not mean closing one’s eyes to manifest crookedness. Some politicians are on ego trips, some are endless showboats, and some are just looking for bribes. But most want to make the city, state, or country a better place — even if their ideas on how to do so may not match up to our own.

Believing that can be hard, but it is a habit we should all cultivate — and demand of our elected representatives.