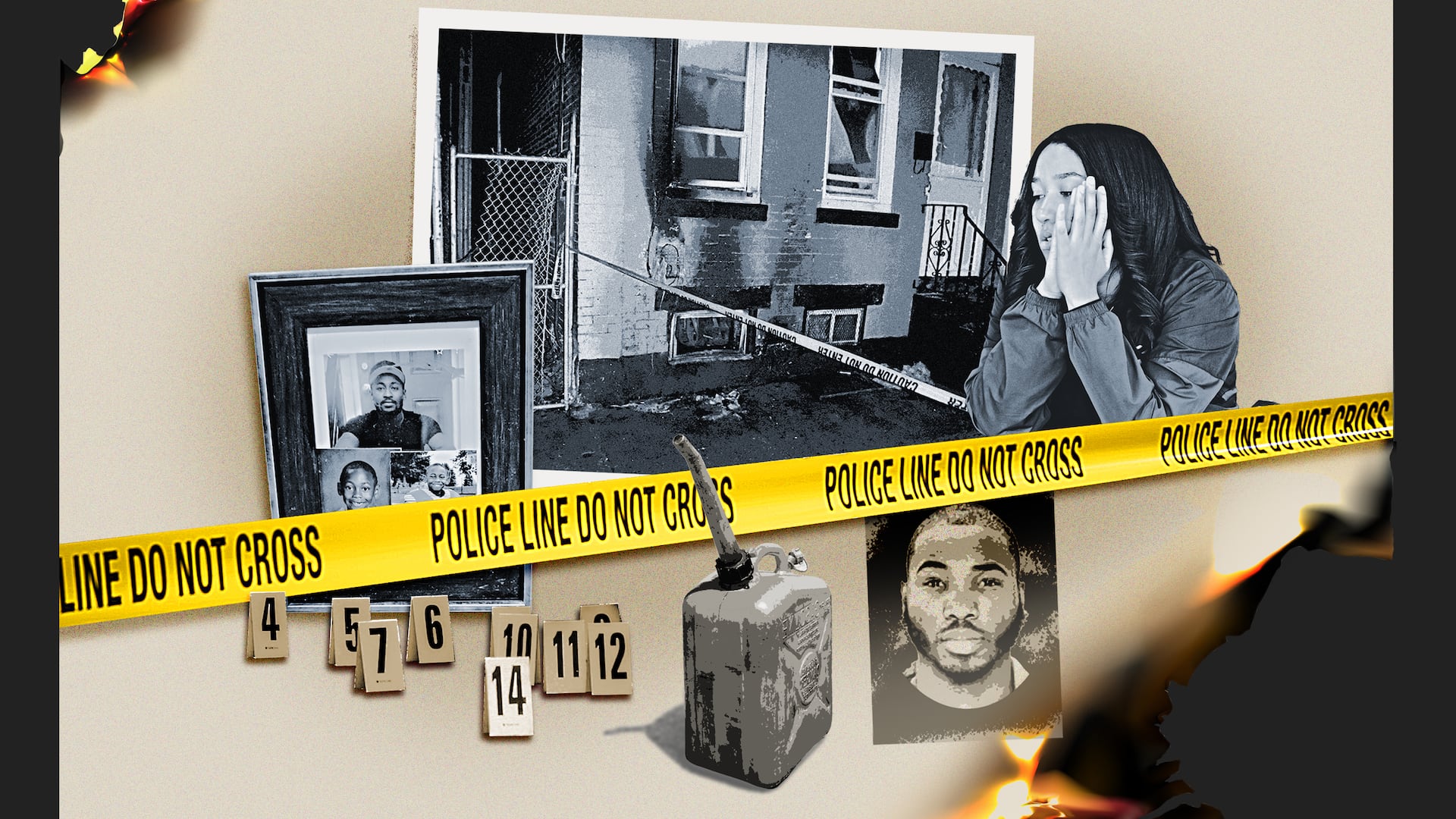

Burning Obsession

To try to win back his ex-girlfriend, a man kidnapped her, burned down homes, and then killed her new boyfriend.

When Christina Parker heard the cracks of gunshots outside her window, she knew that what she’d feared for more than a year had finally happened.

The man who had stalked, threatened, and kidnapped her, who cut off her hair on a subway platform, who even burned down five homes in search of her and her boyfriend, had come to kill his rival.

She waited a moment before walking outside. Then, still in her slippers, she shuffled onto Ludlow Street.

There, lying on the pavement in his own blood, was Naseem Smith, with bullet holes throughout his body. Smith had tried to give Parker a fresh start, had given her hope, had loved her.

Now he was about to die. All for some twisted form of revenge that could — and should — have been prevented by police.

Parker knew who’d pulled the trigger: Markevon Durham. Her ex.

She had broken up with him a year earlier after a tumultuous, yearslong relationship that began when she was in high school. She ended things after learning he’d lied about his age and the fact that he was married with children, but Durham refused to move on, and instead, began his streak of terror.

For months as the crimes unfolded, Parker, Smith, and their loved ones had begged for help from Philadelphia law enforcement, telling responding officers and fire marshals that Durham was the one trying to burn them alive. Parker and Smith were at home in Hunting Park when Durham set their house ablaze — twice. In one instance, they told a detective they had seen Durham running away after setting their roof on fire.

But he wasn’t charged — leaving him free to torment Parker and, eventually, to ambush Smith with a gun.

On the night of the shooting — Nov. 8, 2018 — Parker explained it all to Detective Robert Daly at Southwest Detectives.

Durham “felt like Naseem took me away from him,” she said — that if he couldn’t have her, no one could.

Smith’s family corroborated Parker’s account, telling Daly about the crimes that had left their homes in ashes — and detailing how they’d done everything they could to try and get law enforcement to help.

Daly remembers the family screaming at him when they first met him, unloading their frustrations even though he was new to the case: “We told you this would happen!” they said. “This is your fault!”

This month, inside a Philadelphia courtroom, Durham was finally brought to justice. To understand how the case came together, The Inquirer reviewed hundreds of pages of police and court records, interviewed victims, police, and prosecutors, and attended the weeks-long trial at which Durham was convicted of crimes including third-degree murder, attempted murder, arson, kidnapping, and aggravated assault.

The outcome stirred mixed emotions for many of those closest to it: gratitude that Durham was finally held accountable, but agony that it took so long.

“I don’t think I’ll ever feel whole again,” Parker, 27, said through tears in a recent interview. “When Naseem passed away, it was like I lost a part of myself.”

“If they would’ve listened in the first place,” she said of law enforcement, “it never would’ve happened.”

Parker was 17 when she met Durham at a Planet Fitness gym. It was 2014, and she was in her final year of high school at YESPhilly. Durham told Parker he was 21, and they went on to date for three years. He even took her to her senior prom.

Then, in the summer of 2017, Parker learned that Durham was married with two children and was at least three years older than he’d said.

She ended the relationship.

Not long afterward, Parker started dating Smith. They had met at the Wawa at Broad and Walnut Streets, where they both worked. She was drawn to his smile, his optimism, his upbeat nature.

“He just showed me how I should be loved and should be treated,” she said.

When Durham learned that Parker was dating Smith, he began taking unusual steps to try and win her back: prank calling their relatives, pouring sugar into the gas tank of Smith’s car, even rifling through their trash.

Then he went a step further — and kidnapped Parker.

On Oct. 14, 2017, Durham showed up outside Parker’s dad’s house in Germantown and dragged her into his car. He drove her out to the suburbs, punching, choking, and berating her on the way, she said.

After driving around for hours, Durham took Parker to his cousin’s apartment in Manayunk. There, she said, he tried to sexually assault her.

She thought Durham was going to kill her — and he sent texts to friends afterward boasting that he nearly had.

“I almost killed her, I drove her out to Quakertown,” Durham said in a text the next day, adding: “I f— her life up yo.”

The next morning, Durham gave Parker a ride back to her dad’s house. Days later, she went to a police station to say Durham had hit her, and she then sought and obtained a protection-from-abuse order against him.

His behavior only escalated from there.

A week after the PFA was filed, he set Smith’s house on fire — while Smith and Parker were inside sleeping. Fire investigators found a trail of gas from the first floor into the basement, where a window had been smashed in.

Then, the following week, Durham targeted Smith’s mother, Nashawna Leake.

Leake was working an overnight shift as a receptionist at Project HOME when Durham sneaked behind her house on the 1500 block of Glenwood Avenue and poured gas along its exterior wall. It was 3 a.m., and Leake’s parents and two children, ages 4 and 16, were asleep inside.

Durham lit the flame, and a blaze quickly ripped through the structure.

Leake’s family escaped unharmed, but the house was destroyed, along with most of their belongings.

Leake told a responding police officer and the fire marshal she thought the culprit was the man who had set her son’s house on fire a week earlier: the former boyfriend of her son’s new girlfriend.

“That is the only person I would have any problems with,” she said later. “We don’t have enemies.”

The next morning, on Nov. 8, someone shot at Smith’s cousin outside the house they shared on the 1300 block of West Jerome Street. No one was struck, but Smith called police and told responding officers he suspected the shooter was Durham.

Then, in December, Durham showed up outside Parker’s job at the Center City Wawa. Parker said he approached her to talk about getting back together, then followed her onto an elevator and down to the Broad Street Line concourse. As she tried to walk away, Parker said, Durham grabbed her, pulled out a pair of scissors, and cut off part of her ponytail.

Parker flagged down SEPTA police, and Durham was taken into custody and charged with simple assault and violating his PFA.

Bail was set at $5,000, but he paid the requisite 10% — $500 — to secure his release the next day.

At his job, a coworker would later recall, he’d waved Parker’s sheared hair around to brag to his colleagues.

“He said that cutting her hair would ruin her life,” said Anitra Stevens, “because it was the most precious thing on her body.”

After the holidays, the harassment expanded to new targets, including Smith’s former girlfriend, Erika Cole, the mother of his son.

She and Smith had dated in 2017 — before he began dating Parker — and on Jan. 1, 2018, Cole gave birth to their baby boy.

Ten days later, Cole received a strange message on Facebook from an account with the name Brittney Tellall.

“Hey I know you don’t know me but congratulations with your new baby he’s adorable!” it began. The message then went on to ask for details about Smith and Parker’s relationship.

Cole didn’t reply.

Less than 24 hours later, her house was set on fire.

She was breastfeeding her baby at 4 a.m., she said, when she saw an “explosion of orange and heard a sound kind of like thunder.” She ran outside into the freezing cold with her baby. Three family members also escaped unharmed.

But by the time firefighters got the flames under control, the house was ruined.

Cole told fire marshals she believed the culprit was the stranger behind the mysterious Facebook message from the day before.

As the attacks escalated, Smith’s relatives weren’t the only targets. His home, on Jerome Street, was set ablaze a second time, in January 2018.

He and Parker were again inside. And this time, after the fire started, they saw Durham running away.

Detective Luz Varela, who responded to the scene, made a note of that, police records show, but never sought to have Durham arrested.

Ten months later, in November 2018, Smith was shot and killed on Ludlow Street.

When Daly, the detective assigned to the shooting, began to investigate and interviewed Parker, she said she was sure that Durham was the killer. She described the string of crimes that led up to the gunfire and said she was angry that no one in law enforcement had seemed to listen or recognize the growing threat.

“When Naseem passed away, it was like I lost a part of myself.”

Daly found police reports detailing all of the earlier incidents, including the Jerome Street fire in which Parker and Smith said they had seen Durham fleeing the scene. Daly applied for an arrest warrant for that crime almost immediately.

Durham, he said, “should’ve been arrested after that statement.”

“How [the detective] handled that case was wrong,” Daly later testified. “… It does not represent what our oath is.”

(Varela, the other detective, said by phone after Durham’s conviction that she did not recall the case or her role in it and therefore could not comment.)

Once Durham was behind bars for the arson, Daly began subpoenaing records and gathering evidence to investigate the rest of the allegations: the killing, the other fires, the stalking.

The case, he said, “just kept growing.”

Cell-phone records showed that Durham was using his phone near the scene at the time of every one of the fires.

He had also used a background-check tool to look up people’s addresses and phone numbers. When Daly subpoenaed Durham’s account, it showed hundreds of searches for relatives of Smith and Parker, including every house that had been set on fire.

And when Daly cross-referenced those records with the cell-phone location data, he learned that Durham was conducting searches on Smith’s family while driving around the blocks where they lived.

“I would call that diligence,” the detective said.

It wasn’t until Daly’s third or fourth conversation with Parker that she told him about Durham’s initial crime: the kidnapping. It was as if she had gone through so much torment that she’d partially blocked the terrifying encounter from her memory, he said.

Parker couldn’t recall the date she had been snatched, or precisely where she was taken when Durham drove her to the suburbs. But when Daly reviewed Durham’s cell-phone and Google records, he saw the evidence hiding in plain sight: GPS coordinates from Oct. 14, 2017, showed that Durham had driven to Parker’s father’s house, then to Quakertown, and back to Manayunk.

By October 2019 — about 11 months after Durham was charged with one of the arsons — Daly’s investigation had led to charges in every other incident, including Smith’s slaying, Parker’s kidnapping, and four more arsons.

At his trial this fall, Durham chose to act as his own lawyer, a decision that put him in a position to question many of the people he’d been accused of trying to kill.

At times, that strategy seemed to backfire. As he questioned Smith’s mother about the torching of her house, she identified him as the perpetrator.

“It was you,” she said.

When he questioned Parker, she said: “You set fires to people’s houses that were in Naseem’s life. You kidnapped me. You cut my hair. You harassed us. And we didn’t have issues with anyone outside you.”

Durham, for his part, told the judge he had been wrongfully accused. He said that the evidence in the case was entirely circumstantial, based on digital records that were unreliable or misinterpreted, and that the detective had force-fed information to Parker and to Smith’s family.

“How [the detective] handled that case was wrong … It does not represent what our oath is.”

Durham testified on his own behalf and said he was the one who had dumped Parker. He called her crude and obscene names and sought to paint her and Smith as the aggressors in a long-running love triangle.

He admitted that he cut Parker’s hair and said he had driven her to Quakertown once. But he insisted that he hadn’t threatened her or held her against her will. And he told the judge there was insufficient evidence to prove he had committed any crime.

“No pertinent testimony or evidence was raised in this case,” he said.

Common Pleas Court Judge J. Scott O’Keefe disagreed.

He convicted Durham on all counts.

Parker sobbed as the verdict was delivered.

“It felt like a weight was lifted — not off my shoulders, but my body,” she said later.

With the trial behind her, she said, she hopes to make peace with her loss and finally try to move forward.

“Naseem was a beautiful person inside and out. He taught me a lot of things,” Parker said. “I learned my worth from being with that man.”

Smith’s mother, meanwhile, said her son’s death, and her belief that it could have been prevented, had changed her. It’s made her angry at times, she said, and caused her to lose sleep.

But she knows Smith wouldn’t want bitterness to overwhelm her. So she does her best to carry on in his memory.

“I can hear him,” she said. “I can hear him saying it’s going to be all right.”

When Daly was first assigned to Smith’s shooting, he was part of Southwest Detectives, where he investigated crimes such as shootings and robberies. Once Smith’s case became a murder, he requested permission to stay with it. He has since been promoted to the Homicide Unit, where he has become one of the department’s top experts in digital forensics.

Durham, now 34, faces decades in prison. Sentencing is scheduled for January.

He’s also awaiting trial on charges that while he was incarcerated last year, he and two other inmates attacked a jail guard, stole his keys and radio, held him hostage, and tried to take over their cellblock.

Assistant District Attorney Cydney Pope, who prosecuted the case, said that Durham’s crime spree was unlike any she had handled in her career — that he had “tortured” his victims for months in a cruel and senseless manner.

“These are individuals who, by virtue of being related to a man who was dating [Durham’s] ex-girlfriend, were being punished over and over again,” Pope said. “The fact that more people did not die is extraordinary.”