A 17-year-old was shot and killed last year. Police listed him as a man in his 20s and his story went untold.

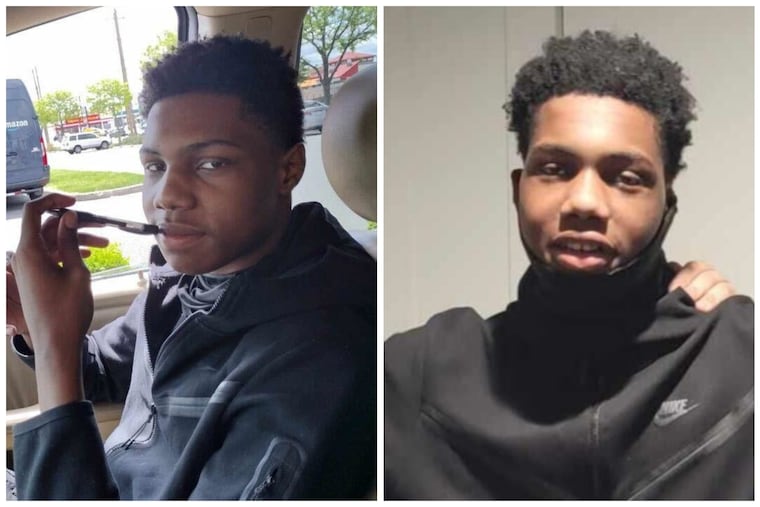

Jordan Jackson, 17, like many victims of violence, had endured a troubled life before his death.

Just before midnight on July 28, police found the body of a young man on a sidewalk in Northeast Philadelphia. He’d been shot once in the head, and died before officers arrived.

The victim had no form of identification, police said. He was wearing a medical face mask and blue latex gloves. A gun was at his side.

In an email to reporters the next morning outlining the night’s violence, police noted the homicide.

“An approximately mid-20s Black male ‘John Doe’ was shot once in the head,” officials wrote. They entered him into the city’s shooting database without an age.

A few days later, investigators would learn that the victim was actually 17 years old — a young man named Jordan Jackson, who, like many victims of violence, had endured a painful, troubled life before his death, including in the moments just before he was killed.

Police never updated the media or its public shooting database with Jackson’s correct age or identity, a sad reality in a city that records hundreds of homicides each year.

That left his mother, Toya Cobb, feeling as if her son had been forgotten.

» READ MORE: These are the 24 children lost to Philadelphia’s gun violence in 2023

Cobb contacted The Inquirer after reading Forever Young, a project that chronicled the life of every Philadelphian under 18 who was shot and killed in 2023. Because Jackson’s age was never updated by police, his death was not listed in police records alongside the other juvenile victims.

But Cobb wants people to know the story of her son and the issues he faced before his death: his childhood trauma compounded by a learning disability and mental health diagnosis; how he cycled through six schools, dropped out of 10th grade, then fell in with friends who were infatuated with guns and crimes.

“He wasn’t perfect, but ... he never had a chance to turn his life around,” she said.

“I just want people to know he wasn’t a man in his 20s,” she said. “He was still a child.”

‘A lot of mothers are in this situation’

Jordan Rush Jackson was born Nov. 25, 2005, and lived in North and Northeast Philadelphia for most of his life. He was Cobb’s first child, the eldest of four, and loved the Chicago Bulls, video games, and riding bikes with friends. His laugh, Cobb said, was infectious.

As Cobb worked multiple jobs as a single mother, Jackson’s grandmother helped raise him for the first few years of his life.

But when Jackson was about 4 years old, his grandmother died of a sudden illness. Cobb said that loss changed something in him. She recalls how he ran through the house calling his grandmother’s name, how even years later, when he was 10, he would suddenly burst into tears at the dinner table.

“I miss Mom-mom,” she recalled him saying.

Jackson’s learning disability and mental health troubles led him to act out in school and at home, Cobb said. He cycled through five different schools before he was 14. She’ll never forget, she said, when a middle school counselor told her, “The only way you can get help for him is if he gets locked up.”

He was only 11.

Two years later, he was arrested and charged with assault for fighting, Cobb said, and started to run away. He was twice admitted to a residential behavioral treatment facility, and each time, she said, he came home traumatized, begging that he never have to return.

In 2022, Cobb said it felt as if things were back on track. He was doing better in school, living at home, and spending more time with family. They spent that summer making memories at amusement and water parks, and the beach in Atlantic City.

But that fall, when he was just 16, he learned he was going to be a father. His behavior started to spiral, Cobb said — he was hanging out with new people, stopped coming home, and he started arguing more with his mother. Two weeks into his sophomore year of high school, he dropped out. His mental health worsened, but he refused medication, his mother said, then he moved in with his girlfriend. At one point, they were homeless and living in a shelter.

Cobb said she struggled to control her son — he was strong and nearly 6-foot-6, and she couldn’t physically force him to stay.

“I feel like a lot of mothers are in this situation,” she said. “What do you do when your 16- or 17-year-old son wants to run the streets?”

Cobb eventually gained full custody of her grandson, and she saw Jackson more often as he came to visit his child. Seeing her baby hold his child, she said, is a memory she will hold forever — how he smothered his son in kisses, how he spoke of wanting to be better. He enrolled in weekly therapy.

But in early July, Jackson was arrested for carjacking. He refused to go to the court-mandated crisis center, then cut off the GPS tracker on his ankle, and went on the lam, she said.

Cobb felt at her wits’ end.

Then, on July 24, he came to her house. He said he was hungry and thirsty, and wanted to see the baby.

But Cobb said she couldn’t open the door — a judge had ordered that he wasn’t allowed to see the child without scheduled supervision, and she knew he was on the run. Painfully, she spoke to him only through her Ring camera intercom before he left.

“He was unstable,” she said through tears.

Four days later, on July 28, he was shot and killed at Bridge and Langdon Streets in Summerdale.

‘He does have a voice’

Staff Inspector Ernest Ransom said homicide detectives still don’t fully understand what happened the night Jackson was killed. He said one shell casing was found next to the teen’s body, and police were unable to find any surveillance footage of the shooting. No arrest has been made.

A source close to the investigation said one theory is that Jackson may have been planning to commit a robbery just before he was killed. His mother said that although that could be true, she believes from conversations with others that the person he was with that night may have set him up.

Cobb said she thinks that her son’s case has been treated differently because of his criminal history and how he was found when he was killed: masked and with a gun. She worries, she said, that because police never shared information about his death with the public, investigators are missing out on potential leads.

Ransom said detectives are still actively investigating, and that there had been developments in the case as recently as this month, though he declined to share details.

“It’s not forgotten,” Ransom said. “We’re trying to bring closure to this case and find out what happened to this individual because he does have a voice.”

Cobb hopes that’s true. She has moved out of Philadelphia in search of a fresh start.

On a recent day, she sat in her home, looking toward the mantel, decorated with a collection of photos of her son, and a black urn holding his ashes.

“Jordan just wanted to be something,” she said.

She fell quiet, looked down at her grandson, and shook her head.

She’s not quite sure, she said, what that something was — and she doesn’t think he knew, either. But now, she said, she will never know.