North Philly man who killed lover before burning his body convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole

Kylen Pratt left Naasire Johnson's charred remains in Fairmount Park in February 2022, prosecutors said.

A North Philadelphia man prosecutors say fatally shot his lover before burning his body and leaving the charred remains in Fairmount Park in 2022 was found guilty of first-degree murder, authorities said.

After a jury on Friday convicted Kylen Pratt, 23, of first-degree murder, abuse of corpse and related crimes in the killing of Naasire Johnson, Judge Giovanni Campbell sentenced Pratt to life in prison without the possibility of parole, followed by a consecutive term of 4½ to 9 years, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office said.

An attorney for Pratt could not immediately be reached.

The February 2022 killing of Johnson was one of the most heinous cases Assistant District Attorney Cydney Pope, who led the prosecution, had seen, she said at a news conference Monday. Johnson’s body was so charred and burned when investigators found it at the Glendinning Rock Park they could not immediately determine if the remains were human, she said.

It took investigators a week to identify the body as that of Johnson, said Pope.

“This body was the worst burned body I have ever seen,” said Pope. “It was worse than any body I’ve ever seen inside an arson. Inside a house.”

Pratt and Johnson had been in a sexual relationship, prosecutors said, and Pratt lured Johnson to his Brewerytown home with a plan: to kill Johnson to stop him from disclosing their relationship.

“Make no mistake about it,” said Pope. “This was a hate crime.”

“This is an individual who was killed because he was gay,” she added. “And because the man who killed him did not want anyone to find out that he was in a relationship with him or that he had sex with other men. Plain and simple. It is absolutely one of the most abhorrent crimes I have ever prosecuted.”

Prosecutors say on the night of Feb. 17, 2022, Johnson went to Pratt’s home on the 2900 block of Oxford Street, where Pratt shot him in the neck, killing him. Pratt then moved Johnson’s body to a secluded cobblestone trail in Fairmount Park, where his body was found three days later, severely charred, wrapped in plastic and a bedsheet, said Pope.

The next month, a tip from an anonymous caller led police to Pratt, who was known as 29th Street Rich by Johnson’s family, said Pope. Pratt was jailed on unrelated charges at the time.

Cell phone records showed that Pratt was with Johnson the night of his murder and that Pratt was on the trail in Fairmount Park at the time police believe he set Johnson’s body on fire, said Pope.

During a search of Pratt’s home, police found a bedroom carpet that been cleaned with bleach, said Pope. The carpet had been cleaned so thoroughly, investigators had to dig under the carpet to the padding and hardwood floor that was soaked in Johnson’s blood, she said.

Police also recovered a 9mm gun that provided forensic evidence linking Pratt to the crime, prosecutors said.

Investigators discovered internet searches on Pratt’s phone looking for news coverage of Johnson’s death. Evidence from Pratt’s phone also showed he made searches such as “murdering in cold blood,” “having sex with dead bodies,” and “traits of a psychopath,” said Pope.

Pratt’s conviction and sentencing offered the family some small form of closure, said Hakeem Pitts, one of Johnson’s cousins and an interfaith minister. But the crime’s effects are felt long after, he said.

“These types of crimes are not just individual tragedies. They infect entire communities,” said Pitts. “LGBTQIA people, especially Black and Brown people, members of our community we suffer a profound psychological and physical health effects.”

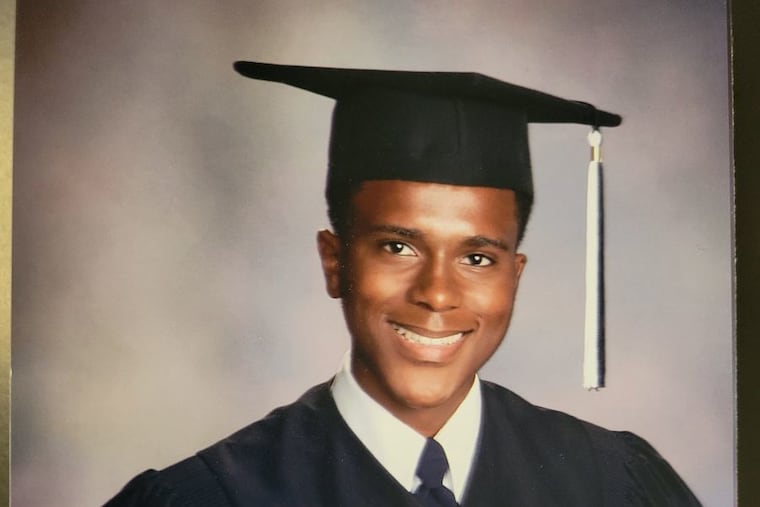

Cynthia Johnson, Johnson’s grandmother, raised Johnson since he was one. Surrounded by family at Monday’s news conference, Johnson’s grandmother recalled her “lovable” grandson, who had just graduated from Architecture and Design Charter High School and was planning to go to community college.

A slide show of photos slowly flashed moments of Johnson’s life. A party as a young boy, smiling next to a relative. A photo of an older Johnson posing in a gray suit and bow tie. And a photo of him wearing his graduation cap and gown, smiling as he holds a sign that read “Class of 2019.”

“Everybody liked him. Nobody could say anything bad about him,” she said, tearfully. “My heart is so torn in so many pieces.”