The Bucks County man who helped spark the Jan. 6 Capitol riot says he was mistreated by prosecutors and in prison

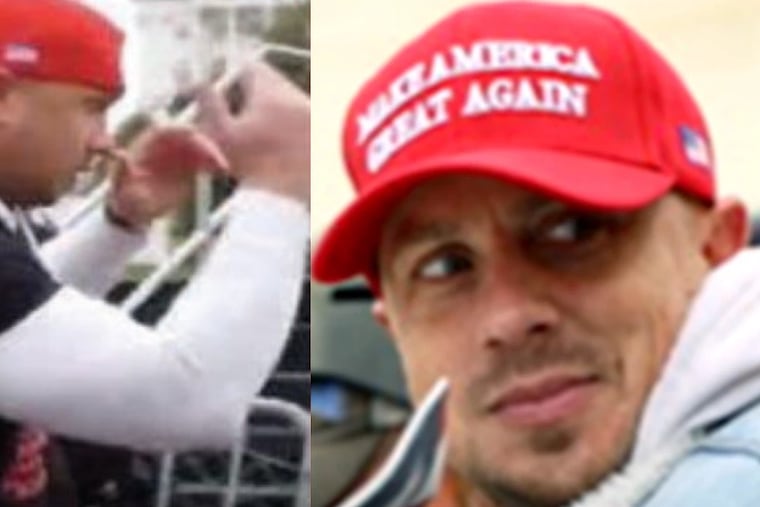

Ryan Samsel, who broke through a Capitol barricade, was among the 1,500 Jan. 6 defendants to get a presidential pardon.

The Bucks County man who was the first person to break through a metal barricade outside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, acknowledges that his actions effectively kick-started the historic riot that left scores of police officers injured and threatened the peaceful transfer of presidential power.

But Ryan Samsel, who was among the roughly 1,500 defendants to receive a pardon from President Donald Trump — the intended beneficiary of the Capitol attack — also said he believes he became something of a scapegoat over the last four years: overcharged by federal prosecutors, unfairly villainized in the public discourse, and subject to mistreatment while behind bars.

Just days before he was granted clemency, prosecutors said they planned to ask a judge to sentence Samsel to 20 years in prison, a term that would have been among the longest for any Jan. 6 defendant. Now, he’s free.

“I’m not saying I wasn’t wrong. I’m not saying I was totally innocent,” Samsel said in an interview. But, he added, “I don’t think my action warrants 20 years. People kill people and get 20 years.”

The 41-year-old’s remarks came as the fallout from Trump’s pardons for convicted rioters continues to reverberate across the country. In the weeks since Trump effectively wiped away all criminal consequences for those accused of participating in the attack, the Republican president has faced criticism from nearly all sides of the political spectrum, particularly over his decision to issue blanket pardons to both nonviolent protesters and those accused of assaulting police.

Other Philadelphia-area residents have benefited — including Zach Rehl, a Port Richmond native and former head of the Philadelphia Proud Boys, who was convicted of seditious conspiracy for serving as one of the attack’s lead provocateurs. Trump commuted Rehl’s 15-year sentence, freeing him from prison. Rehl has since said he hopes to have the commutation upgraded to a pardon, a more expansive form of relief that Trump issued to almost every person charged with or convicted of any crime stemming from the Jan. 6 melee.

More than 1,200 people were convicted of crimes for their actions on that day. Some were charged with trespassing, while others were prosecuted for assaulting law enforcement officers. Justice Department officials said the probe was the largest single investigation in its history. But Trump had long accused prosecutors of abusing their power and targeting political opponents, calling defendants “hostages” while seeking to downplay the gravity of what occurred during the attack.

Samsel, of Bristol, was a key part of how the riot began.

Prosecutors said he and four other men — who did not know one another — toppled metal barricades outside the Capitol as a crowd began to swell behind them. Their shove broke the building’s security perimeter and caused Capitol Police Officer Caroline Edwards to fall, hit her head on a metal handrail, and lose consciousness.

At Samsel’s trial in Washington, prosecutors said he and his codefendants “cleared the way … for the hours of terror, violence, destruction and injury that followed.” He was convicted last year of charges including civil disorder and assaulting a police officer, and he was scheduled to be sentenced next month.

Samsel, in the interview, said it’s true that he was the person who first breached the Capitol perimeter, and that his shove of the barricade caused Edwards to fall. But he said he didn’t act alone. He didn’t mean to knock Edwards over, he said, and tried to help to her feet after she fell to the ground. And he said he never went inside the Capitol as rioters poured into the building.

In fact, he said, he had only gone to the Capitol grounds because he thought Trump might speak there. While Samsel didn’t deny acting aggressively at times, he said he never intentionally struck an officer, and added: “When I started seeing people fist-fighting with the cops … I said, ‘It’s time for us to go.’”

He ended up in federal custody not long after the attack, and for years was shuttled between jails as he awaited trial. He regularly complained of being assaulted by guards and not receiving adequate medical treatment. Prosecutors, in court documents, often accused him of lying or fabricating materials to support his claims, something he denied in the interview.

In any case, Samsel said, he was exposed to what he described as “horrific” conditions while incarcerated, including having to spend lengthy amounts of time in solitary confinement, or in cells without toilets. He also said he communicated with Rehl through the toilet pipes while both were incarcerated at the same jail, and — in an assertion that could not be independently verified — he said he saw famous defendants including Sean “Diddy” Combs and Luigi Mangione while he was recently housed at the federal jail in Brooklyn.

Now, Samsel — a barber who used to work in Center City — said he hopes to dedicate at least some of his time to working on prison reform. He said he has reached out to elected officials from both parties to connect on the issue, including U.S. Sen. John Fetterman, a Pennsylvania Democrat; U.S. Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick, a Bucks County Republican; and Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, a Democrat and frequent Trump critic.

As for his past, Samsel said he has “deep remorse” for crimes he committed in the years before Jan. 6, 2021, including assaults against women. In one of those incidents in 2010, he shoved his pregnant girlfriend into a canal.

Federal prosecutors said in recent court documents that he remained the subject of an active warrant for a 2019 assault in New Jersey; Samsel said he had to agree to a payment plan to resolve that case this month and secure his release from federal prison.

When reflecting on what happened at the Capitol, Samsel said he doesn’t have regrets, believing that the fallout from that day has helped put him on a new path.

“I wouldn’t [say I] regret it, because I believe good can come from it,” he said, “and if I have to sacrifice my own freedom, then I will do that.”