In 1968, a pandemic hit pro sports, including the Eagles. No one remembers it or its lessons. | Mike Sielski

As our professional sports leagues and the NCAA lurch toward the resumption of games and matches after three months of silence, it’s fascinating and instructive to look back at how institutions responded to a nearly forgotten pandemic five decades before.

Suppose it happened now the way it happened then. Can you imagine? A pandemic — originating in China, no less — sweeping across continents and oceans to the United States, where it kills 100,000 people. A virus scything through locker rooms all over the East Coast, infecting the NBA’s most respected player, forcing one college basketball team to postpone a game because so many of its players were sick, spreading to five players on the Eagles and leeching 15 pounds from the team’s starting tailback as he stays in bed for the better part of a week, aching and vomiting and burning with fever.

The H3N2 virus strain, known at the time as the Hong Kong flu, reached America’s shores in September 1968. And as our professional sports leagues and the NCAA lurch toward the resumption of games and matches after three months of silence, it’s fascinating and instructive to look back at how those institutions responded to a pandemic that occupies little space in our collective memory more than half a century later.

And what did those institutions do?

Nothing.

And what did we learn from it?

Nothing.

The NFL, the NBA, and the NHL did not stop their seasons. There were still college football games on Saturday afternoons and college basketball games on midweek nights. There was no discussion of holding events without fans or in containment sites. Sports generally went on as if nothing were out of the ordinary, even as the nation found itself “in the midst of an epidemic of Hong Kong flu,” according to The New York Times, and “deaths from pneumonia and influenza … exceeded normal expectations” into December. By then, H3N2 had already been documented in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and as an indication of the virus’ danger, the Times cited the Dec. 12, 1968, death of actress Tallulah Bankhead, “who died of pneumonia, which she developed after she was stricken with Hong Kong flu.”

» READ MORE: People were staying home from sports before the pandemic. What will happen once the games resume? | Mike Sielski

Now, as a recent Wall Street Journal story noted, mortality rates for H3N2 “were significantly lower than those of COVID-19.” But 100,000 dead is still 100,000 dead. Yet leagues, teams, even those athletes who had contracted H3N2, and the media who covered them reacted with little alarm over and appreciation for, if any at all, the virus’ potential damage — a shortsighted posture that, based on the dawdling over COVID-19 in February and early March, ought to be familiar to all of us.

On Thursday, Nov. 21, 1968, for instance, the Eagles announced that one of their running backs, Izzy Lang, had missed practice that day because of viral pneumonia and would miss the team’s next game, against the Cleveland Browns. In fact, James E. Nixon, the team doctor, determined that Lang could not practice or work out for another six days. Three other players — defensive end Mel Tom, wide receiver Ben Hawkins, and defensive end Dean Wink — and team trainer Moose Detty also sat out that Thursday practice; they had the flu. All of those developments warranted just a 65-word dispatch from the Associated Press.

» READ MORE: What would sports look like with smaller or no crowds? | Mike Jensen

Tom and Wink missed practice again the following day, more discouraging news for an Eagles team that would lose its first 11 games, finish 2-12, and see its season — and Philadelphia sports history — further marred by the quasi-apocryphal booing of Santa Claus during a loss to the Minnesota Vikings on Dec. 15. “They’ve had injuries, a winless season, fines, and suspensions,” Ray Kelly of the Courier-Post wrote on Nov. 23, 1968. “Now the Hong Kong flu is after them.”

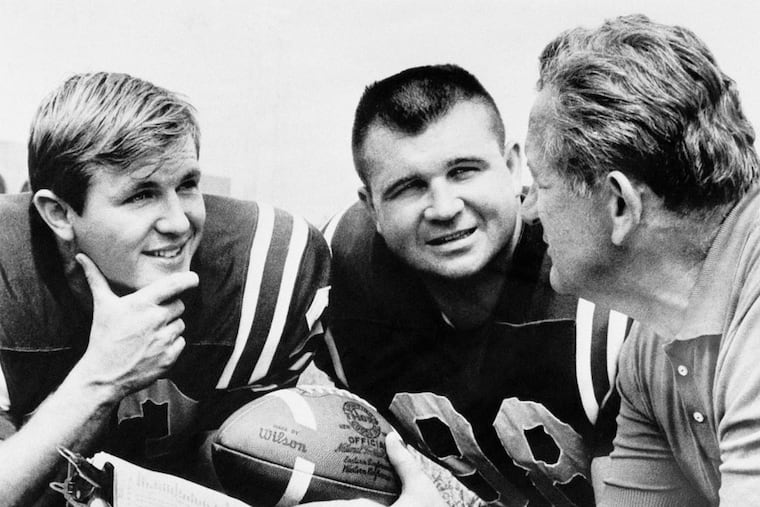

The virus already had afflicted tailback Tom Woodeshick, who had sat out the entire week of practice ahead of the Eagles’ Nov. 10 game against the Redskins. His symptoms so debilitated him that his weight fell from 220 pounds at the beginning of the week to 205 by its end.

“When it came to playing in the game, I was really weak,” Woodeshick, who rushed for 947 yards and three touchdowns during the ’68 season, said in a recent phone interview. “I was shocked I was able to sustain the entire 60 minutes. But I did. How I did it, I don’t know. Not effectively, but I did.”

Four New York Giants players stricken with H3N2, including rookie halfback Bobby Duhon, missed practice on Thursday, Dec. 5. To this day, Duhon doesn’t remember how he contracted it.

“It did knock me down for four or five weeks,” he said in a phone interview from his home near Atlanta. “It wasn’t a flu that lasted for three or four days. It was four or five weeks. But it wasn’t that big a deal publicity-wise and nationwide. It wasn’t like it was in the papers.”

No, it wasn’t. Even given the major news stories of that time — the aftermath of the 1968 presidential election, Vietnam, social and racial unrest — the scattered, muted treatment of the N3H2 pandemic feels quaint compared with the saturated coverage of the coronavirus today. And while the nanosecond-by-nanosecond tracking these days of even the most trivial matters has its obvious harms and drawbacks, newspapers’ limited coverage of H3N2 then seems incomplete and almost dismissive of the virus’ actual and potential ramifications.

Take the lead-up to a Dec. 10, 1968, NBA game between the Boston Celtics and Baltimore Bullets. Gene Shue, the Bullets coach, had spent three days in bed “with the Hong Kong flu that has struck nearly half of Baltimore,” according to the Evening Sun. But the bigger story line was that Bill Russell — who was not only the Celtics’ starting center but also their head coach — had missed the team’s two previous games because of H3N2. Picture a story of comparable significance today. Picture LeBron James testing positive for COVID-19.

Or, picture a college basketball team so overtaken by the coronavirus that it doesn’t have enough healthy players to put a team on the court. No one was prepared for that possibility in early March, but perhaps we should have been.

The University of Delaware men’s basketball team was supposed to play Rutgers on Dec. 14, 1968, but so many of the Blue Hens, including coach Dan Peterson, contracted H3N2 that Delaware had to postpone the game. Peterson gathered his players for a practice two days later, but not without reservations.

“What I’m afraid of is a relapse if some of them start working out too soon,” he told the Wilmington News-Journal then. “We’ll have to guard against that.”

Peterson, his players, and all those who survived the H3N2 pandemic were fortunate. A vaccine was developed four months after the virus arose, and instead of recognizing that outbreak for what it was — a warning, a call to prepare for something worse to come — we allowed it to fade from our minds and our history. Buried in ancient newspaper clippings, those anecdotes and incidents from our longtime pastimes, from the games we play, might seem insignificant now. But they happened, and we — our government officials, our civic leaders, ourselves — allowed them to stay buried. We failed to heed the lesson. We remembered so little. And here we are.