Dick Vermeil and Carl Peterson built the 1980 Eagles and a wine-soaked friendship that persists to this day | David Murphy

The architects of the Eagles' 1980 Super Bowl team are now partners in a Napa Valley winery. This is the story of 45 years of football and friendship.

Christmastime, Southern California, around midnight: A ’69 Volkswagen coupe eases off the 405 and heads east through the quiet streets.

The man behind the wheel is chasing something, though he does not know what. At least, not concretely. What he does know is that the man who is waiting for him wants the same thing. And while the exact manifestation of this desire will not reveal itself for another seven years, both men will end the night convinced they were meant to chase it together.

And so the man behind the wheel heads east, and the man who is waiting for him heads downstairs to the parking lot where they will meet. They are young men, one more so than the other. Like most of their generation, they are fortunate to be so. That month, the newspapers would carry the story of a 32-year-old special-operations officer from Ohio gunned down southwest of Saigon.

In different circumstances, who knows? Even all these later, any thought of those days elicits thoughts of those who did not get to live them. Every generation is defined by its circumstances. These would be theirs.

Back home, Pepper Rodgers was leaving UCLA for Georgia Tech, and several members of his staff were hoping not to follow.

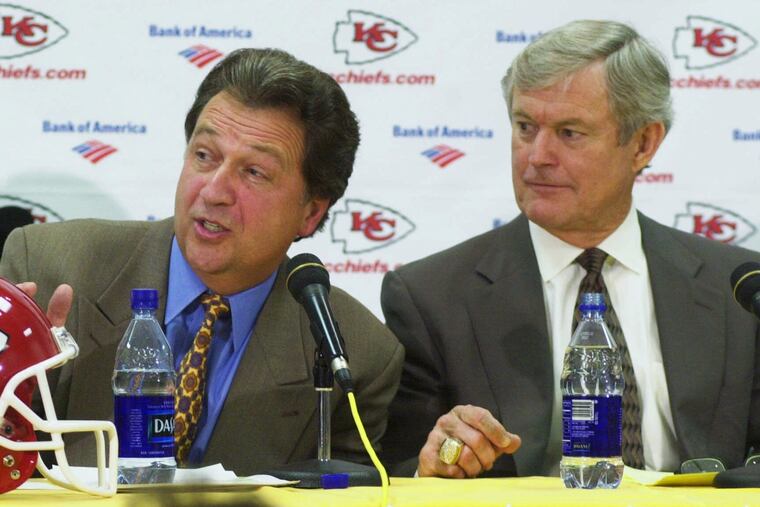

Carl Peterson had spent his life in Southern California, most recently as a graduate assistant for the Bruins. Dick Vermeil, an assistant coach with the NFL’s Rams, had been hired as Rodgers’ replacement. But the Rams were in the playoffs, and that meant time was scarce. The three hours he’d found for interviews happened to be the first three of the morning.

So that is where it begins: after midnight, in a parking lot, outside a makeshift office building, where the Rams share space with the local municipal golf course. Vermeil likes what he hears from Peterson, and later offers him a job. The year is 1973.

The trophy

Late January, 1981, the Louisiana Superdome: A fledgling personnel director stands against the wall of a locker room at halftime and tries to process what he sees. Fear? Probably not the appropriate word. War, recession, pandemic -- that’s fear. Maybe Charlie Johnson felt fear during the nine months he spent driving a Jeep around Da Nang. But not playing defensive tackle.

Whatever it was, Carl Peterson had never seen it in his seven years with Dick Vermeil. Something about him demanded a complete dedication to the cause, whether it was a 6 a.m. staff meeting or a five-mile run.

During their first spring at UCLA, he’d listened as Rams coach Chuck Knox delivered a heartfelt toast to his former assistant while a group of Rams and Bruins coaches were out to dinner. This wasn’t a simple professional courtesy -- Knox was standing on top of the restaurant table. A good leader earns your respect. A great leader smiles as you shout it from the rooftops.

For Peterson, that had meant giving up coaching after nearly a decade of working his way toward the top. After two years at UCLA and a two-touchdown Rose Bowl victory over heavily favored Ohio State, Vermeil had accepted Leonard Tose’s offer to return to the NFL. He’d brought Peterson with him to the Eagles, but after a disappointing first season the head coach decided that he needed a trusted voice in the front office.

Three years later, the Eagles’ victory over the Cowboys in the NFC championship game served as a fitting testament to the move. Shortly after transitioning to the front office, Peterson had spent several weeks following a longtime scout named Jackie Graves on a tour of the nation’s historically black colleges.

At the time, Graves had been particularly high on a running back from Abilene Christian who lacked a prototypical NFL body. Trust me, Graves had told him, this young man has compensating ability.

It was a phrase that Graves would repeat more than once in May 1977: in the fifth round, when they drafted a defensive back out of Kansas, in the sixth, when they took another one from Tennessee State.

“Carl,” Graves would say, “this young man has compensating ability.”

The following spring, Peterson assembled his coaches and scouts in a conference room at Veterans Stadium. Pick by pick, they watched the nation’s best college players disappear from their board. By the time the Eagles’ first selection arrived, 119 of them were gone, none of them Graves’ guy.

“Carl,” Graves said, “he has compensating ability.”

Three years after the Eagles finally selected Wilbert Montgomery with the 154th overall pick, the diminutive running back compensated them with a 194-yard rushing performance in their win that put them in the Super Bowl.

The team they took to New Orleans featured plenty of similar players. Charlie Johnson, Reggie Wilkes, Dennis Harrison, Tony Franklin, Max Runager -- all came in the third round or later. Jerry Robinson, Petey Perot, and Roynell Young came in the first and second rounds in ’79 and ’80.

Yet when it came to a stage like the Super Bowl, the players were not the only rookies. The veteran coaches whom Vermeil had consulted about his schedule structure for the two weeks before the game had advised him to ease up on the intensity of work during the week before the game. But given Vermeil’s unfamiliarity with such a concept, perhaps he needed a definition.

The week of the game, the Eagles were an hour into practice at an outdoor field near the New Orleans airport when a downpour chased them into the locker room. So Vermeil bused them to the Superdome.

“The pace Dick went at in his career, his life, was just extraordinary," Peterson says. "I don’t know anybody who could survive with his energy and intensity on four hours’ sleep like Dick Vermeil. You couldn’t stay up with him. And on top of that, he’d work out like a demon.”

Whether it was the work or the stage or the talent of the opponent, the only time the Eagles had a chance in Super Bowl XV was the pregame introductions. Down 14-3 at halftime, Vermeil desperately tried to command his players’ focus.

“But they were in a coma," Peterson said. “That’s one of the few times I can ever remember that happening.”

The separation

Winter 1982, the bowels of Veterans Stadium: A familiar silhouette appears in an office doorway. There is a concerned look on Marion Campbell’s face.

“You should talk to Dick,” the Eagles’ defensive coordinator says. “He isn’t doing well."

Later, Peterson visits with his friend. It has been only two years since they returned from New Orleans buoyed by the thought of their next Super Bowl together. In the meantime, life has intervened.

Peterson accepted a generous offer to run the fledgling USFL’s franchise in Philadelphia, while Vermeil found himself stuck in the middle of a contract dispute between the NFL and its players. The strike began after two weeks of play. Neither the team nor its coach was able to recover.

““I could tell he was getting to the end of his rope,” Peterson says now. “He was worn out. Mentally. Physically.”

It takes another seven years for Peterson to think it might be done for good. The Chiefs hire him as their president and general manager. He tries to hire Vermeil as his head coach. Instead, the Chiefs’ preseason television broadcast gets a new color analyst.

““I didn’t want to end up in the same hole I was in when I left,” Vermeil says now. “I didn’t think that I could do that.”

For eight more years, that is how it goes, Peterson leading the Chiefs out of irrelevance, Vermeil announcing their least relevant games. They speak every Friday, sometimes more, and visit in the summer.

Peterson drafts Derrick Thomas, acquires Joe Montana, and falls in love with a Kansas girl. Vermeil finds himself enjoying the broadcasting life, and his vast property in Chester County. The Chiefs get within a game of the Super Bowl in 1993. That’s the closest they will come.

The trophy again

Late January, 2000, the Georgia Dome in Atlanta: A veteran NFL executive stands quietly on the sideline and tries to process what he sees. In the middle of an artificial turf field, a 63-year-old coach guides a football team through its final preparations. There is little about him that would stand out to the casual observer. But from a vantage point of 19 years, the change is startling to see.

Truth be told, he’d expected this, however long it took. There’d been a tinge of disappointment on that day in 1997 when Vermeil announced he was ending his 14-year hiatus. Not only would he be coaching in the same state as the Chiefs, he’d be doing it with the organization in which they both began.

Peterson already had a coach, and a future Hall of Famer at that. But he also knew that the opportunity to avenge that night in New Orleans might finally be dead.

Still, the decades had taught him a thing or two about the value of these opportunities. When he’d arrived in Kansas City, the folks liked to tell a story about some players from the Chiefs’ 1969 championship team who skipped the parade to attend the Pro Bowl. Hey, they’d figured, there’ll be more parades.

He’d finished 1999 in one of those confrontations with mortality that will periodically plague any NFL executive. The previous year, longtime head coach Marty Schottenheimer had departed for the Washington Redskins. The Chiefs finished 9-7 under new head coach Gunther Cunningham but missed the playoffs for the second straight season.

Meanwhile, he watched from afar as Vermeil’s once-moribund Rams became the Greatest Show on Turf.

“You always say you’ll be back next year," Peterson says now. “Well, it doesn’t happen that way.”

Years later, Peterson will remember plenty about that week of Super Bowl XXXIV, starting with the moment he watched Vermeil lift that trophy above his head. Mostly though, he will remember the man whom he saw at that walk-through.

“I’ve never seen him so relaxed,” Peterson says.

Vintage Vermeil

With any luck, this August in Calistoga, Calif., there will be an old coach on a tractor. And, perhaps, an old friend will join him.

Wine had always been in Vermeil’s blood, and that is not just a figure of speech. Great-grandfather Jean Louis Vermeil emigrated to America during the 1890s gold rush. He brought the family recipe to California, passed it down to a grandson named Jean Louis II, who in turn passed it to a son familiarly known as Dick. Every year, he returns to the local vineyard to help with the harvest.

In 1999, Vermeil fulfilled a lifelong quest when he partnered with a Chester County winery to produce a vintage that bore his family name. In fact, two years later, it was over a glass of Jean Louis Vermeil cabernet that he fulfilled another longtime dream.

After stepping down from the Rams in the wake of the Super Bowl win, Vermeil and his confidants quickly understood that he’d made a grave mistake.

“Dick’s essence is leading men, young men, to a collective goal,” Peterson says. “And he still had more to give.”

This time, Peterson had a job to give him, and would not take no for an answer. In 2001, after another mediocre season, the Chiefs executive parted ways with Cunningham, then hopped on a plane to Philadelphia and drove to Chester County.

“We went over to a Sovana Bistro, drank a bottle of Vermeil wine, and said, let’s go back to work," Vermeil says.

They were partners then, and they are partners still. In 2008, Vermeil launched his own winery in the Napa Valley, with Peterson among the founding investors. Today, the coach pours his energy into selling wine; Vermeil Wines currently produces 2,500 cases a year.

“The NFL has 32 teams,” he says. “There are over 500 wineries in the Napa Valley. One of the things we have to overcome -- when you have a sports figure’s name on a bottle, it can still be good.”

As for the Chiefs. . .

“It was a great five years," says Vermeil, 83. "My only disappointment, one of the only in my entire career, was not being able to do a good enough job to hand Lamar Hunt a trophy.”

Team founder and owner Hunt died less than six months after Vermeil announced his third and final retirement, in December 2005. Three years later, Peterson left the Chiefs.

Peterson, 76, spends most of his time on a private cruise ship, where he and his wife own a condo. While he never got a chance to hand a trophy to Hunt, this February he finally got the opportunity to feel the thing for himself.

When the Chiefs beat the 49ers in Miami to claim their first Super Bowl in 50 years, the roster still featured one holdover from Peterson’s tenure: punter Dustin Colquitt, whom he’d drafted in the third round in 2005. In the celebratory aftermath, Peterson tracked down Andy Reid and delivered a long-simmering message.

“Andy,” he said, “Thanks for accomplishing the mission.”

Peterson attended the parade.