Dick Vermeil’s place in Eagles and NFL history is secure. The Hall of Fame could be next.

Vermeil, now 85, led the Eagles to their first Super Bowl, and won it all with the Rams in 1999. The Pro Football Hall of Fame inductees will be announced Thursday night.

The UCLA football team had just shocked the nation in the Rose Bowl, taking down Ohio State coach Woody Hayes’ undefeated Buckeyes, 23-10, on New Year’s Day, 1976.

Dick Vermeil, then the 39-year-old Bruins coach, was “feeling full of my oats and confidence” after the epic win, which came only two years into his UCLA head-coaching stint. Vermeil oozed confidence, and felt he could bring greater glory to UCLA’s football program, which had only one title in the trophy case from the 1954 championship.

Then Vermeil’s phone rang.

On the other line was Philadelphia Eagles owner Leonard Tose and general manager Jim Murray. They told Vermeil they were flying west to meet with him. They wanted to talk about hiring Vermeil to coach the lowly Eagles.

“They caught me on a Monday and I wouldn’t meet with them, because I had no intention of leaving,” Vermeil, 85, says now. “I felt we could win a national championship at UCLA.”

Tose and Murray, however, weren’t going to give up that easily and leave L.A. empty-handed. They called Vermeil again. And again. Finally Vermeil acquiesced and met with the NFL owner and front office executive. Two days after that sit-down, the California-born (Calistoga) Vermeil had committed to a new contract, and was about to uproot his family and move to the City of Brotherly Love.

“My coaching staff at UCLA all said, ‘Coach, you’re crazy not to take that opportunity. Go!’ So I was headed east, much to the dismay of my family,” says Vermeil.

Despite prior coaching stops at Stanford, the Los Angeles Rams, and UCLA, Vermeil arrived in southeastern Pennsylvania with no immediate football connections or ties. Even worse, he took over a team knowing that he had no first-, second- or third-round draft picks for the next two years (1976-77), and no first- and second-rounders for 1978.

“I knew it was going to be a challenge,” Vermeil says now.

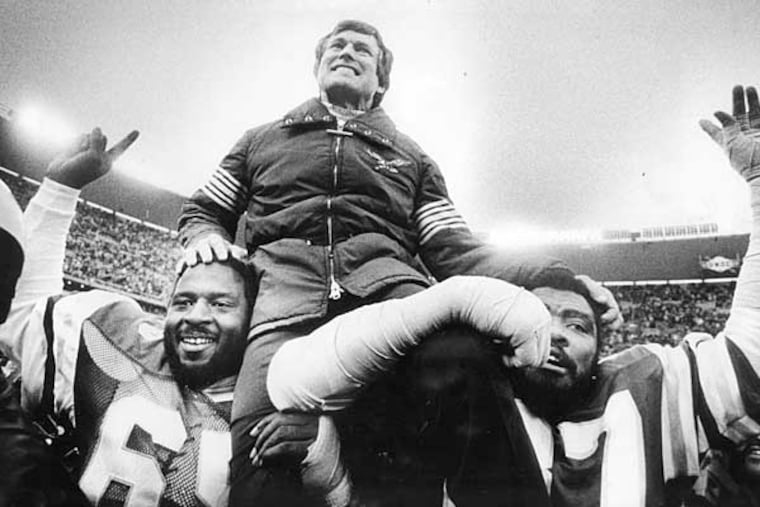

But it took Vermeil only four years to turn the Philly franchise’s fortunes and guide the Eagles to their first Super Bowlin the 1980 season. And while that Eagles team lost to the Oakland Raiders, 27-10, Vermeil had already changed the Eagles’ culture and image from perennial doormat to playoff contender. Vermeil retired — for the first time — after the Eagles’ 1982 season, but he cemented an important chapter in his football coaching arc. His career resumed in 1997 with the St. Louis Rams, culminating in that club’s first Super Bowl title, and Vermeil finally hung up the headphones for good after the 2005 season, when he was the Kansas City Chiefs’ head coach.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame is missing from Vermeil’s legacy, although that could change Thursday when the Class of 2022 is announced. Vermeil is the lone coaching candidate, and everyone from his coaching contemporaries to his former players say it’s time for Vermeil to join the football greats in Canton, Ohio.

“Without a doubt. Not even a question,” says former Eagles quarterback Ron Jaworski, when asked about Vermeil’s Hall of Fame chances. “It is very, very difficult to get into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. You have to have a great resume. And [Vermeil’s] resume is outstanding. I truly believe he will get in.”

“There’s so much about [Vermeil’s] resume, and who he is, what he meant to the game and his players, without a doubt, he belongs there in that conversation,” says Hall of Famer Kurt Warner, Vermeil’s Super Bowl-winning quarterback for the Rams.

And Hall of Fame coach Tom Flores, who opposed Vermeil in Super Bowl XV, said that although Vermeil doesn’t hold the record in certain statistical categories, “he’s shown that he’s a winning coach, that he’s a world champion-type of coach, so why not?”

“People go into the Hall of Fame for various reasons. Not all are the wins and the losses or the glamour of the teams you might have coached,” Flores says. “But I have no doubt” about Vermeil’s Hall chances.

On to Philadelphia

There was plenty of doubt hovering over Philadelphia and old Veterans Stadium when Vermeil came aboard for the 1976 season. The Eagles hadn’t been to the playoffs, much less played meaningful games, for years.

Vermeil inherited Mike Boryla and an aging Roman Gabriel for his debut season coaching the Eagles, and neither quarterback was the answer to shifting the team’s fortunes on offense, at least in Vermeil’s eyes.

“Boryla wasn’t going to be my quarterback after a while, I could just tell that,” Vermeil says. “He had played well the year before (1975). But he just didn’t fit for us. And Gabe was at the end of his career.”

While Vermeil was coaching with the Rams prior to his UCLA stint, he got to know Jaworski, their young quarterback who had been drafted by the club in 1973. When Vermeil began the Eagles’ rebuild after that 4-10 1976 season, he knew who he wanted behind center. Vermeil dispatched Carl Peterson — who came from UCLA to Philly with Vermeil and later became the Eagles’ personnel director — to go to L.A.

“I said, ‘Go see [Rams GM] Don Klosterman, and don’t come home unless you can come home with Ron Jaworski’ ” Vermeil says now with a laugh. “I loved [Jaworski’s] innocence. So real, and authentic. He was what he was and I loved it. You could see he had ability. Hell, he could throw a ball through a car wash without getting it wet when he was young. I mean that ball whistled when he threw that thing.”

In a franchise-changing trade, the Eagles dealt All-Pro tight end Charle Young for Jaworski, nicknamed “The Polish Rifle” and “Jaws” . Jaworski calls Vermeil “my second dad,” and credits his former coach with instilling discipline and structure in the young QB’s life.

With Jaworski now slinging passes, Vermeil had one of several cornerstones in place for an Eagles resurgence. There was also Hall of Fame wide receiver Harold Carmichael — “I think Harold Carmichael initiated the process of showing NFL receivers how to catch the uncatchable ball,” says Vermeil — and running back Wilbert Montgomery. On defense, there were stalwarts like linebacker Bill Bergey and lineman Carl Hairston, and key role players like cornerback Herman Edwards.

“We were a team like the city, we were tough. And that’s what (Eagles fans) want — they want toughness,” said Edwards, now the Arizona State coach. “Just play hard. And we did that. Coach Vermeil forced you to live up to your talent. He had a standard that was set, what it meant to be an Eagle.”

In Vermeil’s mind, the Eagles’ signature game was five games into the 1979 season, when the defending Super Bowl champion Pittsburgh Steelers came to the Vet. Jaworski played before Veterans Stadium fans as a visiting player — “Fans were throwing golf balls from the 700-level. I said, ‘This place is crazy!’ ” Jaworski recalls — but it was a different story when you wore an Eagles uniform.

And they upset the world champs.

“It just stunned the city. The crowd, the people, from that time on, the city was a believer in what we were doing,” says Vermeil, referring to that 17-14 win over Pittsburgh. “The players believed in what we were doing.”

Adds Jaworski: “That was the signature win that made people stand up and say, ‘I think the Eagles are building something there.’ ”

Tose brought Vermeil to Philly to play for the chance at the brass ring, and during the 1980 season the Eagles delivered on every promise, except on the biggest stage in New Orleans.

“The memories coming from Super Bowl XV are that we didn’t have a chance to win,” says Flores, the former Raiders coach. “We were pretty big underdogs.”

Instead, the Raiders rolled to victory, and Eagles tight end Keith Krepfle caught a Jaworski pass for the Eagles’ only touchdown late in the game. “My claim to fame,” jokes Krepfle. “Unfortunately, we didn’t have a good game as a team.”

“We didn’t play well,” adds Vermeil of Super Bowl XV. “That means I didn’t coach well. Everyone says we lost the game because I overworked them. Everybody said we won the championship game [against Dallas] because I worked them so hard. The only thing that matters when you get in those two big games is to win it. I learned it takes the same thing to get to a Super Bowl and lose as it does to get there and win. You’ve got to get there.”

Vermeil said he became “lifelong friends” with Tose, and that the late Eagles owner “treated me with great respect” and “gave me control to make all football decisions.”

But two years after the Super Bowl run, Vermeil, in his words, “needed a break,” and retired from coaching for the first time. He still refers to the lead up to his hiatus as burnout, but also says there were other factors.

» READ MORE: After burning out with Eagles, Vermeil has the perspective and energy only time can bring

“I allowed my passion to become an obsession,” Vermeil says. “It just sort of consumed me.”

“I was shocked,” said Hairston, the former Eagles defensive lineman, referring to Vermeil leaving after the 1982 season. “It bothered me, but I knew in his heart he probably felt that was the best thing for him to do at the time.”

Into the booth

In the broadcast booth, Vermeil proved to have more than enough experience and acumen to be a talented football analyst.

“He was by far the most thorough analyst that I ever worked alongside in any sport. Period,” says Brent Musburger, the longtime sports broadcaster who worked with Vermeil at ABC calling college football games. “No one, and I mean no one, did more homework than Dick Vermeil prior to a game. It’s not even close.”

Vermeil says that during his 14-year window away from the sidelines — he was a CBS and ABC broadcaster — he was continually approached by NFL teams to make a return. Tampa Bay owner Hugh Culverhouse, Vermeil said, opened up his coffers, but Vermeil turned down the offer.

“I could write my own contract. [Culverhouse] said, ‘You come and coach my football team. I have more money than I could spend in many lifetimes. But I’m tired of losing. Please come and coach my team,’ ” Vermeil says.

There was even a possible return engagement with the Eagles and new owner Jeffrey Lurie in the mid-1990s, but Vermeil says the deal fell through. (Lurie hired Ray Rhodes).

“I came very, very close to coming [back],” Vermeil says. “I just felt after my first long meeting with [Lurie], after I said I would take the job, I had been out [of coaching] at that time 12 years and I didn’t feel confident I would be strong enough, fast enough to be successful with an organization that was brand new [ownership].”

The Rams, however, represented for Vermeil another chance to reach the mountaintop, as well as amenities available to him that he didn’t enjoy in his first NFL coaching stint.

“I had first- and second-round picks. Every year,” Vermeil says. “I could make trades. I could get Marshall Faulk for a second-round pick and I had an extra second-round(er). I could draft Orlando Pace. I also knew, if I don’t do it now, at that age, in my 60s, no one else is going to offer me a [coaching] job, and I might live the rest of my life regretting that I didn’t get back in, so I took the job.”

The mountain top

It took two losing seasons in St. Louis for Vermeil to reverse course and lead the Rams to Super Bowl glory. In one of the most exciting NFL title games in history, the Tennessee Titans drove downfield and came within an arm’s length of scoring a touchdown that — with a successful extra point — would have tied the game. Instead, the Rams’ Mike Jones stopped Kevin Dyson short of the goal line.

“I couldn’t see if [the Titans] scored or not. I turned my attention to the head linesman,” Vermeil says. “When he put his arms up, then I put my arms up. That was it.”

“When anybody asks me about coaches, the first person that comes to mind is Dick Vermeil,” said Warner, who was the Super Bowl XXXIV MVP. “The amazing thing was, we were really only together for two years, and really just one year I was playing and in that [starting] role. That’s the amazing thing, the kind of impact he had on me. He wanted to be successful on the field. But it always transcended that, he wanted the best for every one of his players.”

Even Vermeil’s former Eagles players were pulling for him to win Super Bowl XXXIV after the Birds’ runner-up result against the Raiders almost two decades earlier. Edwards was a coach on the Buccaneers team that lost to Vermeil’s Rams in the 1999 NFC championship game, and afterward, Edwards said he sought out Vermeil on the field to deliver a special message.

“Walking across the field, we embraced. And I look at him and said, ‘Win it for the guys, Coach.’ He knew what I was talking about,” Edwards said. “Not for the Rams so much, which was great, but for the Eagles.”

Jaworski worked that Super Bowl XXXIV for ESPN and says he and his former Eagles teammates “played that game vicariously through Vermeil.

“No doubt about it,” Jaworski says. “We felt like we won. Anyone who’s associated with Dick Vermeil felt that way.”

Vermeil’s second retirement came after that Super Bowl victory, a decision he says he still regrets to this day. “I look back, I wouldn’t make the same decision. I would have stayed,” he says.

A one-year layover led to a final coaching return, this time with Kansas City, but five years with the Chiefs yielded no title.

Still, former Chiefs wideout Dante Hall says Vermeil’s impact on players’ careers is immeasurable.

“One of the greatest humans I’ve ever met,” Hall said. “I can go on and on with the superlatives. I credit him with the longevity that I had in the NFL. We fell a little short in Kansas City, but he took two different franchises to the Super Bowl and won one. Go try and find me the number of coaches that did that.”

Says Hall of Fame tight end Tony Gonzalez: “Loved playing for Coach Vermeil — the best. I would love to see him coach in today’s game, as far as training camp. He definitely liked to push you hard and love you hard. What he meant to the players — just a class act. He’s one of the best ever at cultivating those relationships with the players. And that’s hard to do in the NFL. I’d say the majority of coaches don’t do it. But he was always able to make that work. I don’t know any other coaches that were able to balance that winning and personal relationship side of [the game].”

Hall of Fame coach Bill Parcells says Vermeil more than earned his place in Canton, even if the voting process “has gotten so political,” in Parcells’ words.

“I think the world of Coach Vermeil. I really do,” Parcells says. “I think he was a good example for a lot of young coaches starting out in the league. His diligence and hard work and approach to the game, I think it was something that didn’t go unnoticed, certainly by me.

“He’s a good man. I always had a high regard for him. He was very good to me when I first got in the league as a coach for the Giants. I’ve always been appreciative of that fact. I’m very hopeful that the voters will put him in.”

Carmichael says Vermeil still calls him regularly and supports some of Carmichael’s business endeavors. “He was a great coach and mentor,” Carmichael says. “He deserves to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He earned it.”

For Vermeil – who’s been portrayed twice in film, recently by Dennis Quaid in “American Underdog” and also by Greg Kinnear in the 2006 movie, “Invincible” — having his place among NFL immortals would be the ultimate honor for the Calistoga kid who became a football lifer.

“I’m excited about it, humbled by it,” Vermeil says. “I’m so grateful. I’m so fortunate to be exposed to so many fine players, and fine coaches that have all made positive contributions to my opportunity to maybe be the guy that goes in.”