As Eagles and Bears prepare for another playoff matchup, looking back on the bizarre 1988 Fog Bowl

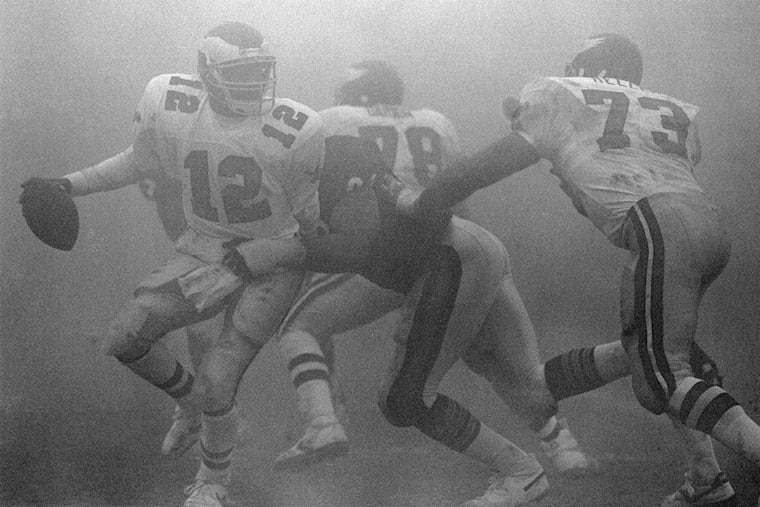

It was bizarre and unforgettable, but the 1988 Fog Bowl still has some former Eagles thinking: Why did they let us play in that mess? Did it have to do with big, bad Buddy Ryan?

At 12:55 p.m. Chicago time on the final day of 1988, the first clouds in what meteorologists would later term an advection fog — the result of moist air from Lake Michigan passing over a cool surface — crept into Soldier Field.

“It was such a bright sunny day that we thought it must be smoke from a nearby fire,” said Ron Howard, then an Eagles public-relations official.

As the southwesterly wind that pushed it there subsided, this miasma of mist stalled over the downtown stadium. For the next two hours, it thickened and lingered, both obscuring and memorializing the second half of a game quickly dubbed the Fog Bowl — a 20-12 Bears victory over the Eagles in an NFC divisional playoff game.

“You couldn’t see from the field to the sideline,” then-Eagles linebacker Seth Joyner recalled this week. “I can still remember Mike Reichenbach running all the way to the sideline to get the call on every single play, then running back to the huddle to give it to us.”

Trailing by 17-9 when the mysterious celestial shroud appeared late in the opening half, Philadelphia could see its way to just one more field goal in the dispiriting loss. The unexpected weather, some on that immensely talented Eagles team still believe, likely cost them their destiny, a Super Bowl appearance.

Thirty years later, as the Eagles and Bears prepare for another playoff meeting in Chicago on Sunday, several questions and at least one conspiracy theory continue to envelop what was one of the most bizarre and well-remembered postseason games in NFL history.

If those Eagles had beaten Chicago, might they have advanced to or even won Super Bowl XXIII? Why wasn’t play stopped in the nearly unplayable conditions? Did one of the officials make the decision to continue? Was it CBS? Or the same NFL executives who so often were mortified and angered by Buddy Ryan and his big, bad Eagles?

One former CBS executive insisted it was the league and not referee Jim Tunney — as was then reported — or the network — as Eagles owner Norman Braman insisted — that made the call to continue.

“Val Pinchbeck [the NFL’s broadcasting chief] was the guy who said, `We’re going to play this game,’” Rick Gentile, then CBS’s director of programming, recalled Thursday.

Though none of Ryan’s five Eagles teams would win a postseason game, Joyner said that the 1988 squad would have gotten by the Bears and challenged the eventual champion 49ers in the following week’s NFC championship game.

“We were equipped to go into San Francisco the following week and give them everything they wanted,” said Joyner, now an NBC Sports Philadelphia commentator. “We felt we could beat that team even on the road.”

All these years later, Joyner also speculated that the infamous fog might have provided the NFL with exactly the cover it needed to keep the troublesome Ryan and his big, bad Eagles out of the sport’s major attraction.

“It’s no secret Buddy wasn’t the most liked head coach in the NFL and his band of misfits weren’t the most liked guys,” Joyner said. “We were snapping necks, breaking legs, and taking names. Maybe they thought, 'OK, they’re down now, what better way to get rid of these guys? If they go to the NFC championship and make it to the Super Bowl, my goodness, is that the image of the NFL we want to portray?’ ”

A mime and a magician

As Chicago’s defensive coordinator, Ryan had helped the Bears and Mike Ditka, the head coach he openly despised and antagonized, win a Super Bowl. Three years later, the feisty Eagles coach was back, hoping to deliver a postseason kick to the groin of both.

En route to the Marriott on Michigan Avenue the night before the Saturday afternoon playoff game, Ryan, who’d bragged that his 10-6 Eagles were superior to the 13-3 Bears “at just about every position,” directed the drivers of the team buses to circle Soldier Field with horns blaring.

Once at the hotel, the NFC East champions gathered in a ballroom anticipating one of the quick and cursory team meetings the details-averse Ryan preferred. But this time the feisty coach, concerned his team might be too tight in its first playoff appearance, had other plans.

“I was in another room at a production meeting with the CBS announcers [Verne Lundquist and Terry Bradshaw] and we were waiting for a few players to join us,” Howard, who now works for the WNBA, remembered. “After an hour or so I sent an intern into the team meeting to see what was happening. He came back and said, `It might be a while. Buddy has a mime and a magician in there.’

“I’ll never forget that. He thought a mime and a magician might loosen them up.”

Saturday morning broke crisp and sunny. The temperature when the 11:30 a.m. (Chicago time) game began was a relatively balmy 35 degrees.

Philadelphia’s vaunted defense broke down early on a 64-yard scoring pass from Mike Tomczak to Dennis McKinnon. But the Eagles settled and a pair of Luis Zendejas field goals cut Chicago’s lead to 7-6 early in the second quarter. Two more Bears scores, a TD and field goal, and another field goal by Zendejas left it 17-9 at halftime.

The Eagles should have been closer, even ahead. Tight end Keith Jackson had dropped a pass in the end zone, and two straight penalties on fullback Anthony Toney had wiped out TD passes — a 9-yarder to Cris Carter and a 14-yarder to Mike Quick — on consecutive second-quarter plays.

“The only thing we felt like could beat us was ourselves,” Reichenbach would say, “and that’s what happened.”

» READ MORE: 25 things to know about the Bears

With only a few minutes left in the half, the first wisps of fog appeared over the stadium. It hadn’t been forecast, but, as it deepened, a flurry of frantic phone calls began among director Andy Kendall and producer Mike Burton in Chicago and Gentile in New York.

“People were going, `Oh my God, we can’t see. What are we going to do,’ ” recalled Gentile. “It was like nothing we’d ever seen. We had 10 cameras, and five were useless. You couldn’t see anything from the press-box level. The main play-by-play cameras were out. So we started scrambling to relocate everything to field level.”

At that point, no NFL postseason game had ever been delayed because of weather. But while a delay wasn’t an option, Gentile said, a postponement was at least considered.

“The issue never seemed to be to wait until the fog lifted,” Gentile said. “If I recall correctly, it was play or no play. I don’t remember them taking seriously the idea of just sitting and waiting until the fog lifted. I mean, there were 70,000 people in the stands.”

Pinchbeck, meanwhile, contacted the network and assured executives the game would continue. An AFC divisional playoff game between Seattle and Cincinnati was scheduled for 4 p.m. on NBC and the NFL wanted no overlap. A year before, the league had signed a record $1.3 billion TV deal with CBS, NBC, ABC, and ESPN.

The decision to continue in the worsening fog incensed Eagles owner Norman Braman and general manager Harry Gamble, both of whom angrily paced the sidelines in the second half.

Braman told reporters he’d “strongly recommended that the game be suspended.”

“I have a picture of me talking to Norman and Harry on the sideline and they have got very pissed-off looks on their faces,” Howard said. “They were none too happy.”

They sought out Jim Noel, a league attorney who was the highest-ranking NFL official present. Gamble told him that a game of this importance shouldn’t be played in such circumstances. They got no satisfaction.

“We told the refs we couldn’t see,” Joyner said. “They said as long as they could see the goalposts, which they couldn’t, we were going to play. They said they had their orders to play.

“It’s a shame because when you have a team that works its tail off to get to this point, you want the most balanced playing field you can create in order for the right outcome to take place,” Joyner said.

Unable to see the field from the TV booth, Lundquist, Bradshaw, and their spotters followed the action on monitors.

“Cunningham drops back,” Lundquist said at one point, “looks, throws, and it’s complete — I guess.”

» MARCUS HAYES: The Bears' Trey Burton is a different player now, but ‘Philly Special’ will always be important to him

Visibility was so poor that network officials conscripted Howard and his Bears counterpart, Ken Valdiserri, to serve as sideline spotters.

“I can remember standing on our sideline and looking across the way,” said Howard. “The fields then were crowned to help with drainage, and you couldn’t see below the players’ knees. Because of the fog, you couldn’t see above their numbers. That was the view from the sideline. At one point, Ken moved back when a play came near. He looked down and saw that he was standing 15 feet on the field.”

With a two-score lead — the NFL didn’t adopt the two-point conversion until 1994 — the Bears were content to run the ball. The Eagles, who relied on Randall Cunningham’s strong arm and quality receivers like Carter, Quick, and Jackson, were more constrained.

“We liked to throw the ball deep and figured we could do that against the Bears,” Cunningham recalled. “But I couldn’t see anybody once they got past five yards. Their linebackers came up and it was difficult to get anything going.”

Cunningham still managed to throw for 407 yards, but his third interception — by safety Maurice Douglass late in the fourth quarter — allowed the Bears to run out the clock. They were routed by the Niners, 28-3, a week later.

After the game, neither Ryan nor his players blamed the weather.

“We’d been imploring the refs about the conditions,” said Joyner. “But after the game was over, what was there to complain about? The NFL should have stopped the game on its own. When it’s done, it’s done. It’s not like they were going to say, `OK, go back and play it.’ ”

Gentile can’t recall what kind of ratings the Fog Bowl got, but he was certain they were better than average.

“It was eerie, but it was also a fascinating three-hour experience,” he said. “You had to watch. You couldn’t really turn away. It’s like when you’re watching football and you see that it’s snowing in Green Bay. Everybody wants to switch to that game.”

When the game ended, Ryan retreated quickly to the locker room. Asked if he had shaken Ditka’s hand, he snapped, “Hell, no.” His next two teams went a combined 21-11 but lost twice in the postseason. He was fired after the 1990 season.

“It’s really a shame,” Joyner said, “because 1988 was our year. We had all the pieces in place. For us to lose that way, it will forever be stuck in our memories.”

Watch the Fog Bowl in its entirety: