M&M’s, baby powder, and blessings: How the Eagles’ Jeff Stoutland became the best O-line coach in football

Stoutland is considered by many to be the finest in the business at his specialty. He is grateful that things went his way on his journey to the NFL.

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — He found his life’s vocation amid the fear that only a young person in his profession can know: the fear of finding out you’re not cut out to be a coach, the fear of having to start over, the fear of getting fired. It was 1986. He was a graduate assistant at Syracuse, not yet 25, working mostly with the Orangemen’s linebackers, and his boss, Dick MacPherson, had just bellowed at him: Come into my office.

It had been two years since, as a college linebacker himself, he had suffered a hit that severed a nerve in his neck. That was when he stopped playing football. It would be 24 years before he would be lying on a bed in a Miami hospital, the right side of his face and neck freezing, as if he were having a stroke, just as he was about to board a plane on a scouting trip. The doctors opened him up for emergency triple-bypass surgery to save him. That was when he finally realized that it was pointless to worry about losing his job and failing to put bread on his family’s table, that he should give coaching everything he had every day just so he could set his head on his pillow each night.

He walked into the office, figuring he had done something wrong that might cost him his career, his heart dropping.

Do me a favor, MacPherson told him. I need you to go over to the offensive line.

“What a blessing that was,” Jeff Stoutland said.

Body slams on Staten Island

Stoutland’s journey to becoming the Eagles’ offensive line coach — and not just the Eagles’ offensive line coach, but the best offensive line coach in the NFL, an offensive line coach who has worked under three head coaches and reached two Super Bowls over his decade with the Eagles, an offensive line coach who has pulled off the rare trick of achieving a cult-hero status among the team’s players and fans — began at Port Richmond High School on Staten Island. The building, 97 years old, made of fading red brick, is wedged in among the capillary streets and tightly packed single-family homes of the island’s Elm Park neighborhood.

Stoutland grew up less than two miles south of the school, on Garrison Avenue in Westerleigh, in one of those kinds of houses: soft periwinkle, flowers growing in a postage-stamp yard, a family of six sharing one bathroom and squeezed into a space of less than 800 square feet.

The neighborhood had been largely Italian and Scandinavian — the Stoutlands traced their roots to Norway — and diversified after World War II as the nearby shipyards drew immigrants for blue-collar and middle-class jobs. The houses were so small and close together that everyone knew everyone else and every adult felt a measure of responsibility for every child.

» READ MORE: Jason Kelce’s career is likely headed for the Hall of Fame. It started with him asking for a scholarship.

“When a kid started crying,” said Ed Mattei, 81, a former Port Richmond teacher who lived down the block from the Stoutlands, “seven doors opened, and seven mothers were on their porches.”

Stoutland’s grandparents owned a deli around the corner. Joyce, his mother, minded the home. Jerry, his father, signed a contract with the Yankees after graduating from Port Richmond and played minor-league ball in their system before entering the Army, serving in the Korean War, and spending 27 years as a New York City firefighter. At the end of their street, no more than 500 yards from their front door, was Westerleigh Park. Giant white oak trees sprout there now, planted in the years since, but as a child, Jeff played a particular brand of touch football there with the neighborhood’s men and boys.

“That’s why I walk like a crooked man,” Mattei said. “Touch football usually came with body slams. You got knocked all over.”

At Port Richmond, Stoutland was a star in two sports: a catcher and first baseman on the baseball team, the captain and a linebacker/lineman on the football team. “Levelheaded, and he was a good leader,” Nick Bilotti, Port Richmond’s head coach at the time, said in a phone interview. “He demonstrated things by his drive. But he did it in a very smooth, quiet way. He wasn’t a loud individual.” He even ran for and was elected the vice president of his class, noting in his campaign statement that “Port Richmond can be made into a better place for all. Lack of student interest in activities is a problem, but … this situation can be improved.”

» READ MORE: How the Eagles’ Lane Johnson draws on his mother’s strength: ‘We’ve been through the road of hard knocks’

On their way to another New England-area college on a recruiting trip, Stoutland and his father stopped at Southern Connecticut State in New Haven. The school had a Division II football program and a brand-new head coach: Kevin Gilbride. The Owls had had just one winning season over the previous six years, but during a campus tour, Gilbride touted the improvements that surely were ahead for the program, including a new stadium. The Stoutlands never continued to the next stop on their trip; Jeff committed to Gilbride and Southern Connecticut State then and there.

“He was my first recruit,” Gilbride, who over his nearly 50 years in coaching has been the offensive coordinator for five NFL teams, said in a phone interview. “Did I know he was going to be a guru? No, but I knew he was a terrific young man who loved the game.”

As a freshman, Stoutland signed up for a roster of morning classes so that he could spend a few hours preparing for practice each day. He’d shower before the sun came up, return to his dorm room with his head still wet, and blow-dry his shock of thick brown hair — a routine that often woke up his roommate and teammate, Bill Ameral.

One day, Ameral retaliated by pouring talcum powder into Stoutland’s hair dryer, then guffawing as Stoutland blasted himself with white dust. But the two, both linebackers, bonded during their anatomy-and-physiology class, diagramming football plays on their desktops using M&M’s. The regular M&M’s were the skill-position players: quarterback, running backs, wide receivers. The bigger, chunkier peanut M&M’s were the linemen.

“Every once in a while,” Ameral said, “you’d find an in-between one. That was the fullback. Those were the days when you had fullbacks and they ran isolation plays. You’d push the M&M’s together, and then one would crunch. When one would crunch, you’d say, ‘OK, he got beat on the block.’”

With Stoutland starting at inside linebacker, Southern Connecticut State went a combined 15-4-1 over his sophomore and junior seasons. But in 1983, in a game late in Stoutland’s senior season, Rhode Island ran a play that the Owls had not practiced against, pulling the backside guard to deliver a blindside block. The guard cracked Stoutland, who already had suffered so many pinched nerves in his upper back and arms that he wore a large collar below his helmet to protect his neck. The collar was no help. The impact cut a nerve.

“Rather than complain about the injury,” Gilbride said, “he said, ‘We didn’t work on that play.’ I said, ‘They didn’t show it.’”

Depressed that he could no longer play, Stoutland got a lifeline when Gilbride suggested that he become a coach while he was still an undergrad, that he commanded enough respect from his teammates that he could make the transition immediately. “We all looked up to him,” Ameral said. “He was one of those guys who was magnetic. All the girls wanted him, and all the guys wanted to be like him.” He joined the Southern Connecticut State staff for the Owls’ final four games that season, then headed to Syracuse. When MacPherson moved him under George DeLeone, the team’s offensive line coach, Stoutland found the mentor who would change the course of his career.

“I owe everything to Coach DeLeone,” Stoutland said. “I loved that man. Taught me everything. Went out of his way. And it was hard. I got my fanny kicked for a long time. But he taught me how to run a meeting. He taught me how to prepare for practice. Without that person in my life, there’s no question you wouldn’t be talking to me.”

A legend in college football

On Nov. 3, 2012, Howie Roseman entered Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, La., minutes before maybe the biggest college football game of that year: No. 1 Alabama vs. No. 5 LSU. Howard Mudd, then the Eagles’ offensive line coach, had said he would retire at the end of the 2012 season, and when Roseman mentioned to Andy Reid that he planned to travel to the game to scout several players, Reid told him, Make sure you talk to Stout.

» READ MORE: The Eagles’ James Bradberry has gone from Samford to Super Bowl LVII. Now he’s going to get P-A-I-D.

By then, Stoutland had coached at five schools before Nick Saban hired him in 2011. Under DeLeone, who died in March at 73, Stoutland had learned to marry his knowledge and background as a linebacker with the brutal teamwork and synchronicity that characterizes terrific offensive line play. “The degree of difficulty is greater, a lot of moving parts going on,” Stoutland said. “You’re relying on five guys up front. I call it the ‘five-wheel drive.’ You can’t be off one. It’s probably why I love it so much — the challenge of putting it all together.”

He developed a habit of teaching his linemen the structure and strategies of defense first. That way, they could identify the movement of defensive linemen and linebackers and, in turn, understand how to use angles and leverage to their advantage in their blocking. “Jeff Stoutland was a legend in college football,” Roseman said. One year into Stoutland’s tenure at Alabama, an NFL team offered him a job. Saban advised him not to take it, telling him, It’s not the right time. It’s not the right organization. You’ve got to trust me on this. So Stoutland did. He turned the offer down.

Joe Pannunzio, then Alabama’s director of football operations, had warned Roseman that Stoutland would be so focused before kickoff that he wouldn’t want to talk to anyone. No matter. Roseman’s father, Steven, had been a teacher and assistant principal at Tottenville High School on Staten Island. He figured that he and Stoutland had a natural connection. He approached him on the field anyway.

“I said, ‘Stout, we’ve got to catch up at the end of the season. We’ve got to get you to the pros,’” Roseman said. “He looked at me like, ‘Get the [expletive] away from me.’”

The Eagles went 4-12 in 2012, and after Jeffrey Lurie fired Reid and hired Chip Kelly, Roseman asked Kelly whom he was considering as his offensive line coach. “He said, ‘Do you know Jeff Stoutland?’” Roseman said. “And it was like perfection.” This time, when Stoutland sought out Saban’s advice, Saban told him, It’s time.

A calling he can’t explain

Stoutland turns 61 on Friday, and for all the places he has worked in his career — New Haven, Syracuse, Cornell, Michigan State, Miami, Alabama, Philadelphia — he sounds like he never left Staten Island, with that strong awk-y accent, with a combination of directness and sentimentality. Get him talking about the Eagles’ offensive linemen, and he’s liable to start welling up. “They’re a special group,” he said here days before Super Bowl LVII against the Chiefs, days after agreeing to a contract extension with the Eagles. “I love them with all my heart.” He watches It’s a Wonderful Life every December with his wife, Allison, and sees himself as a modern-day George Bailey. “There are so many situations where this would have changed if that wouldn’t have happened,” he said. “It really applies to all of us.”

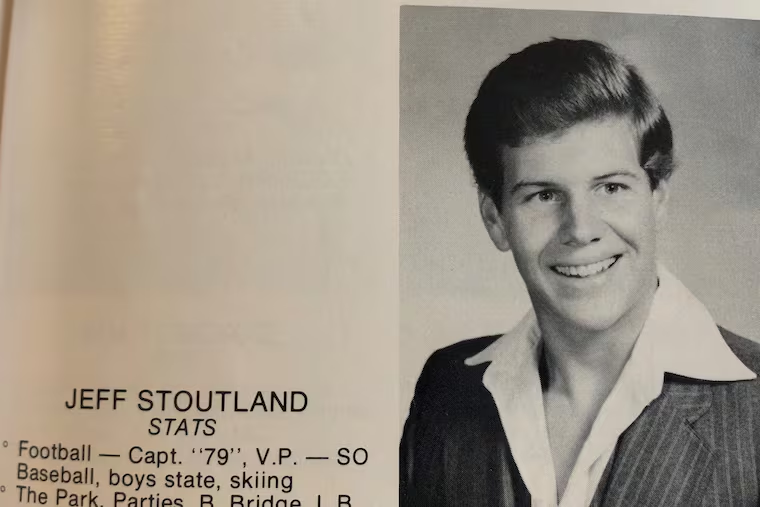

He is still a presence in his old neighborhood, even if he doesn’t live there anymore. “We hold on to that connection,” said Louis Vesce, Port Richmond’s football coach. The school inducted him into its Alumni Hall of Fame in 2015, and Mattei, who sits on its alumni board of directors, and principal Andrew Greenfield were so proud to talk about Stoutland one morning earlier this month that they spread a pile of photographs and photocopied yearbook pages across a conference-room tabletop.

There was a headshot of Jeff Stoutland, Class of 1980. There was Jeff Stoutland, taking a healthy cut at a fastball in one picture and standing among his football teammates in another. There was Jeff Stoutland in black and white, too young then to know what was ahead, so immersed and fulfilled in coaching, his profession so much a part of him now, that he can’t explain what drove him to it.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Some people are called to be a priest.”

» READ MORE: ‘Alligator wrapped in armadillo skin’: Howie Roseman’s passion has the Eagles’ resilient GM back in the Super Bowl