Well before Nick Foles, Earl Morrall was the NFL’s greatest substitute quarterback

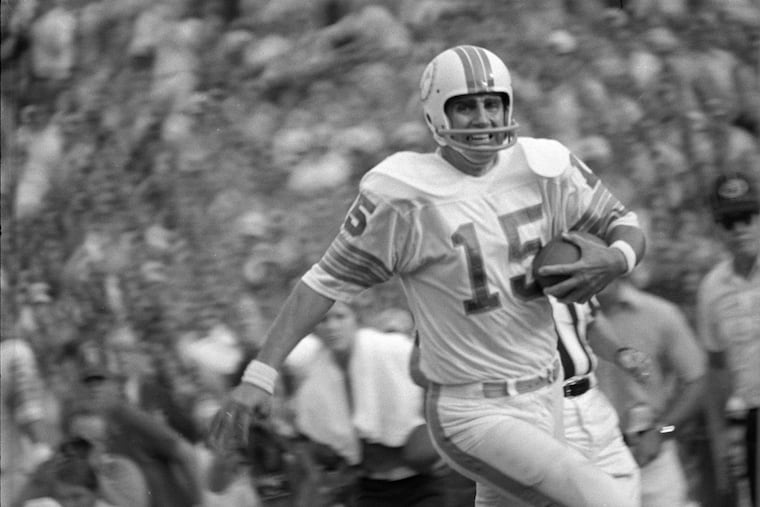

The square-jawed QB with the signature crewcut twice took teams that had lost future Hall of Fame QBs to Super Bowls and won a third as an emergency substitute.

Earl Morrall was a square peg in a round hole — almost literally.

Though the longtime NFL quarterback proudly wore a crewcut throughout the league’s hirsute “Broadway Joe” era — long after even Johnny Unitas had relented — he designed and lived in a circular, futuristic house that resembled a spacecraft.

“It was supposedly hurricane-proof, and he liked the idea of doing something different,” said his son, Matt, 61, a Fort Lauderdale, Fla., attorney. “He was always willing to do things that were unconventional or contrary to his personal appearance.”

That wasn’t the only contradiction in a notable life that ended when, suffering from severe symptoms of brain degeneration, Morrall, 79, died in 2014.

An engineering major at Michigan State, he possessed a reverence for order and efficiency, yet on the field delighted in unleashing bombs. He played a young man’s game until he was 42. In a bawdy Dolphins locker room where his “Sugars!” and “Dadgummits” elicited snickers, he relaxed in a rocking chair. And, despite being a No. 1 draft choice who started 102 NFL games, Morrall saw his lasting fame come as a substitute.

The story of the man who, until these last two postseasons, was the NFL’s ultimate super-sub QB figures to be resurrected during this weekend’s Philadelphia-New Orleans NFC playoff, as TV analysts provide historical context for Nick Foles, the backup quarterback who has spectacularly salvaged consecutive Eagles seasons.

And throughout South Florida on Sunday afternoon, the inevitability of that comparison will put Morrall’s 85-year-old widow, five children, and nine grandchildren in front of their televisions.

“We always watch whenever a backup like Nick steps up like he has, because we know they’re going to mention my dad’s name,” Matt Morrall said. “We’re happy about the success Nick has had. It’s nice to see good people have good things happen to them.”

Just as Foles has twice resuscitated the Eagles' hopes after Carson Wentz injuries, the square-jawed quarterback with the signature retro-cut twice took teams that had lost future Hall of Fame QBs to Super Bowls and won a third as an emergency substitute.

“I see similarities between Nick and my dad,” said Matt Morrall, an offensive lineman at Florida in the 1970s. “My dad had this willingness to be a good teammate and do whatever it took to win. He just wanted to be part of a winning team and didn’t expect more than that. That was his nature, and that seems to track with what Nick is doing with the Eagles.”

In 1968, Morrall replaced an injured Unitas after the preseason and marched the Colts to Super Bowl III. Two years later, during Super Bowl V, he again stepped in after a Unitas injury and rallied Baltimore to a 16-13 victory.

Then, in 1972, when Bob Griese went down in Miami’s fifth game, Morrall quarterbacked the Dolphins to the NFL’s last unbeaten season.

Morrall was smaller and less accurate than Foles and, unlike the Eagles QB, could rely on strong running attacks during his miracle seasons. Like Foles, he was popular in the locker room, suffered his wounds — both emotional and physical — without complaint, and rarely cursed.

“The first time my mom ever heard him swear was when he cut off a portion of his big toe with the lawn mower,” his son recalled. “He came to the kitchen door and asked her for a towel. She thought he was just sweating and said, `I’m on a long-distance call, Earl.’ And he said, '---dammit, get me a towel!’ She dropped the phone, saw the blood, and rushed him to the hospital. He passed out on the way from a loss of blood.”

Both Morrall and Foles played at Michigan State (though the Eagles QB played in only one game before transferring to Arizona). The 6-foot-1, 205-pound Morrall went in the first round to San Francisco, the 6-6, 240-pound Foles in the third round to Philadelphia. Morrall’s first super-sub season came at age 34, Foles’ at 28.

In 21 seasons, Morrall threw for 161 TDs and 148 interceptions and had a QB rating of 74.1. He was the league’s MVP in 1968. In seven seasons, Foles, who was Super Bowl LII’s MVP, has thrown for 68 TDs and 33 interceptions and has a QB rating of 88.5.

Born in a Muskegon, Mich., to a mechanic and his bookkeeper wife, Morrall was a baseball and football star at Michigan State. The Spartans went 9-1 his senior season and beat UCLA in the 1956 Rose Bowl.

The 49ers chose him first in that year’s draft, but he sat behind veteran Y.A. Tittle. It was the first example of what his son termed Morrall’s penchant for “being both in the right place at the right time and the right place at the wrong time.”

He reached four Super Bowls but started just one. No matter where he landed, Morrall encountered a future Hall of Fame QB: Tittle in San Francisco, Len Dawson in Pittsburgh, Fran Tarkenton in New York, Unitas in Baltimore, Griese in Miami.

“He always wanted to play, always wanted to compete,” his son said. “But, sometimes, he had some pretty good people in front of him.”

Morrall prospered at times — 24 TD passes with Detroit in 1963, 22 with the ’65 Giants — then flopped and got benched. Until 1968, he started 10 or more games just three times in 12 seasons. While always popular with teammates, he took heat from fans and from sportswriters, who sometimes labeled him “Bullpen Boy,” “Rag Arm,” and “Mr. Inconsistent.”

“Sometimes, it seemed like everyone had given up on me,” he wrote in an autobiography.

Then came 1968, a memorable season that would contain both his career’s high and low points.

The Colts acquired the 34-year-old as insurance for the aging Unitas. This time, fate worked in Morrall’s favor, as the Baltimore legend went down with an elbow injury in the final exhibition game.

Morrall started all 14 regular-season games, threw for a league-leading 26 touchdowns, led Baltimore to a 13-1 record, and was named the NFL’s MVP.

But even though his Colts were heavy favorites against Joe Namath’s Jets in the Super Bowl, Morrall played poorly. He threw three interceptions and missed a wide-open Jimmy Orr in the end zone on a first-half flea-flicker. Later in the 16-9 loss, Unitas replaced him.

Morrall’s 6-for-17 passing performance was widely criticized, and, for many observers in the late 1960s, his obsolete crewcut made him an easy villain, especially when compared with the brash, long-haired Namath.

“It was a very difficult experience for him,” Matt Morrall said. “It was not something he ever discussed much, other than to say it was a very frustrating experience.”

Morrall won some vindication two years later. When Unitas was hurt in Super Bowl V, his seasoned backup rallied the Colts to two fourth-quarter scores and a 16-13 victory over Dallas.

On the Jim O’Brien field goal in the final seconds that won it for Baltimore, Morrall was both the holder and tension reliever. Noticing the young kicker’s nervousness as they awaited the snap, Morrall turned to O’Brien and said, “Just relax and boot it down the middle.”

It was a role Morrall played often throughout a long football life.

“His young teammates always looked up to him,” Matt Morrall said. “When Howard Schnellenberger hired him to be the quarterbacks coach at the University of Miami, he mentored Jim Kelly, Bernie Kosar, Vinny Testaverde. He enjoyed working with kids.”

The Colts put Morrall on waivers after the ’71 season, and for $90,000, Dolphins coach Don Shula, who had had him in Baltimore, signed the 38-year-old as Griese’s backup.

“Earl used to know everyone’s name and was always the most-liked guy on the team,” Griese said. “There would never have been an undefeated season without Earl Morrall.”

Those Dolphins were 4-0 when, midway through Game 5, Griese’s ankle snapped. Morrall came in and guided the Dolphins to 12 straight victories, including playoff wins over Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

When a sports psychologist asked him to share his secrets for being a successful backup, Morrall listed “sacrificing and keeping the focus on the team rather than yourself,” “working more than necessary,” and “always doing the right thing.”

He got to practice what he preached when Shula reinserted a healthy Griese as his starter for the Dolphins’ Super Bowl VII win over Washington.

“Dad told Coach Shula he didn’t agree with the decision,” Morrall’s son remembered. “He said, `I think I should play, but I’m not going to make a problem.’”

He watched the Dolphins win another Super Bowl in 1973 and retired after the ’76 season. He moved into the strange, new house he’d built, bought a small golf course, and at one point served as mayor of Davie, a Fort Lauderdale suburb, where a street has been renamed “Earl Morrall Pass.”

His last years were marred by ailments likely brought on by all those hits to the head, his son said.

“He came down with Parkinson’s, had some slight dementia problems,” Matt Morrall said. “He lost the ability to project his voice and said it felt like there was a big cotton ball in the middle of his head. … We sent his brain to Boston University, where they found the highest form of CTE.”

But even when he was losing his mind, Morrall reveled in his reputation as the man who had made the NFL’s last perfect season possible, the most reliable backup in league history.

And he kept the crewcut until the day he died.