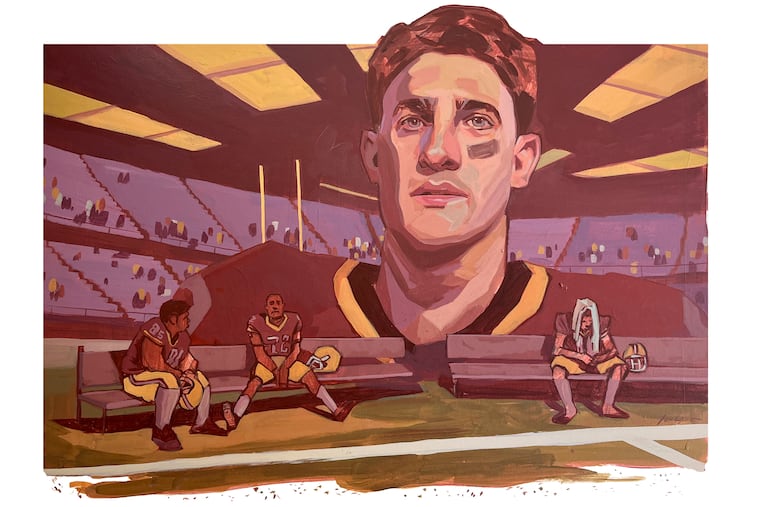

Nick Sirianni’s introduction to ‘pro’ football: Checks bounced, coaches quit, and players boycotted

The Eagles coach was a wide receiver for the Canton Legends in a fledgling indoor football league. Glamorous? Not exactly.

The starting quarterback quit during the fourth quarter of the season opener, the coaches walked out a few weeks later after their checks bounced, and the turf was so thin that it felt like concrete. This — the inaugural season of an indoor football league — was Nick Sirianni’s introduction to professional football, where the players made $300 if they won and $200 if they didn’t. And that’s if the checks cleared.

“Calling it ‘professional’ is using that term very loosely,” said Dan Larlham, who became the quarterback for the Canton Legends when the starter said he had had enough.

Sirianni is one win from coaching in the Super Bowl after leading the Eagles to the top seed in the NFC playoffs. But in 2005, he was a wide receiver in the Atlantic Indoor Football League a year after graduating from Mount Union College in Alliance, Ohio.

It was the lone “professional” season of Sirianni’s playing career, which included three Division III national championships at Mount Union. Sirianni’s professional career could soon reach the pinnacle. It started with a spring football league that didn’t even have enough equipment.

» READ MORE: Before Eagles’ Boston Scott was a ‘Giant killer,’ he was a broke college kid clinging to a dream

“In practice, if someone wanted to sub out, you would take your helmet and shoulder pads off and give it to somebody else when they came in,” said Brandon Carter, one of the team’s defensive backs.

The Legends drafted Sirianni, who had 998 receiving yards and 13 touchdowns in his senior year, in the sixth round. It wasn’t televised or streamed. The players simply received a text from a coach. Most of the players grew up near Canton or played at nearby colleges.

Their coaches — Jay Brophy, Jim Ballard, and Tim Flossie — were football fixtures in a football-crazy town. The new league seemed like a solid idea.

“Football is taken from you,” said Chuck Moore, who played at Mount Union with Sirianni before joining the Legends. “You only get to play for a certain amount of time. The Canton Legends was an opportunity for us to try to get together and do it again for as long as we could.”

The players held jobs during the day and practiced late at night at an indoor soccer facility. Larlham would arrive home after midnight and wake up early the next morning to teach high school algebra. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was a chance for a bunch of 20-somethings to keep their football careers churning. And then the checks bounced.

“I went to take it to the bank and I got a notice in the mail that I owed money because the check bounced,” Carter said. “Mind you, the guy who owned our team owned the whole league. I was like, ‘How are the checks bouncing when you own the whole league?’ It was wild.”

» READ MORE: NFL conference championship betting trends: Tracking 52 years of history

Carter’s game check bounced again, which was enough for him to tell the coaches he was done. They pleaded for him to stay before following him out the door a few weeks later when their pay stopped coming.

The owner, not wanting fans to realize the team didn’t have a coach, stood on the sideline with a headset that wasn’t plugged in. The quarterback called the offensive plays and the linebacker handled the defense.

“I think we actually won,” Larlham said.

Brick wall, concrete floor

Sirianni and the Legends were the type of players who would run through a brick wall. That’s because they literally had to. The sidelines at their home arena — which opened in 1955 — were five-foot brick walls that separated the arena floor from the seats.

“They took like gym mats and drilled them into the wall,” Carter said. “There was hardly any padding. I’m like, ‘Come on, man. You’re going to get somebody killed.’ [The owner] was trying to cut corners as much as he could.”

Larlham said he often had to decide between getting tackled by a 275-pound defender or running into the wall.

“The better choice is the 275-pound dude chasing you,” Larlham said. “The brick wall is undefeated.”

The Legends won just three of their 10 games that season, saving the owner money with each loss. The game ball, Larlham said, felt like it was purchased at Walmart, but the uniforms were decent. They traveled to road games in chartered buses — “That was actually one of the pleasant things,” Larlham said — and saw how the other half lived as they played on modern turf fields with thick padded walls.

“I don’t even know where he found our turf,” Carter said of the owner. “It was like in a closet or something. I’m serious. It was like the old-school, original AstroTurf. No padding underneath it. You want us to play on this?”

“That’s a concrete floor, man,” Moore said. “They basically rolled out a green gymnastics mat and strapped it on and played.”

Their home arena was so small that the corners of the end zone were rounded and the ceiling was in play on kickoffs and deep passes.

“It’s a really cool, old arena and a special place to watch an event,” Larlham said. “But it’s the most unsafe playing surface you could imagine for a football game. Shoot, I’ve seen better indoor-outdoor carpet on my grandma’s back deck. It was rough. But heck, it got rolled out and you’ve been playing it long enough that you say, ‘We get to throw this thing around and get tackled and play still.’ They probably knew it, but I would’ve paid to play. We had a blast.”

Silky receiver

Sirianni balanced his time with the Legends with his first coaching gig as he started his climb toward the NFL as an assistant for two seasons at Mount Union. His playing days were nearing an end, but Sirianni still had game.

“He wasn’t the fastest dude, but he was technique-savvy and ran great routes,” Carter said. “Going up against him in practice, he would get up on you because you know he’s not that fast but then you’re like, ‘Oh crap, I have to get out of my backpedal because he’s on top of me already.’ He was quick. He was one of those blue-collar, put your head down and grind guys. That’s the type of cat he was. He didn’t back down from anyone.”

The Eagles coach who runs up and down the sidelines and jaws at opponents is the wide receiver the Legends knew nearly 20 years ago.

“He’s the same exact way,” said Ballard, who quarterbacked Mount Union to the 1993 national title against Rowan and was the Legends offensive coordinator until the checks stopped coming. “Except he has the headset on now and he’s not in somebody’s ear chirping. He’s a trash talker. And he’s still that way. He was even worse as a player. He’s hyper-competitive. That’s him and that will always be him.”

Sirianni backed the talk up on the 55-yard indoor field, never shying away from contact in a league where the hits were heavy. Carter played Division I football at Toledo and said Sirianni — who followed his two brothers to Mount Union — had the skills to play at that level.

“He was incredibly smooth,” Larlham said. “As a route runner, just silky. Really, really good. It was really easy to throw him the football just because he was always open and always in the right spot.”

Boycotting practice

Moore hurt a knee during training camp but hung around the team all season. He stood on the sidelines, rode the buses to away games, and checked in on practice. He hustled from work one night to make a practice only to see the arena empty. They were down the street, he was told. But that was empty, too.

The players, Moore later learned, were boycotting practice after going a few weeks without their checks. Eventually, the owner paid up and the season rolled on.

“We had to stand unified,” Larlham said. “You can’t just throw us to the wolves.”

Sirianni’s coaching career included stops with three NFL teams before the Eagles hired him. But his professional career — which could soon reach the Super Bowl — started with a dysfunctional season in Canton.

“People don’t believe me that we played, you don’t even call it arena, you call it indoor football and we played on this little team together,” said Mike Winkler, the team’s fullback. “We had a blast while it lasted. Seeing it now, it’s just crazy. Man, he’s been so successful. I remember the first time I saw him on the sideline. ‘Sirianni? Holy crap, man.’ It’s pretty cool.”

Carter heard Sirianni’s name a few seasons ago and had to look him up on the internet to make sure that it was the same Nick he played indoor football with. Larlham had friends over on Saturday and smiled when Sirianni mugged for the camera before a commercial break. That was his old receiver, Larlham told his friends.

The receiver from the Legends is now a win from the Super Bowl. Sirianni no longer has to worry about checks bouncing, the players boycotting, or running into a brick wall. He’s coaching one of the final four NFL teams standing and he’s two wins away from forever being a legend in Philadelphia.

“It catches me off guard every time I see it just because I shared a locker room with that guy and threw passes to him,” Larlham said. “But you knew that he had a pedigree that if that’s what he wanted to do, he was going to get there someday.”

“It was an experience. Definitely a pleasant experience, overall. I’m really glad that I did it. It’s something that you’re fresh out college, ‘I’m not married yet, I have to hang onto something. Let’s see what I can do.’”