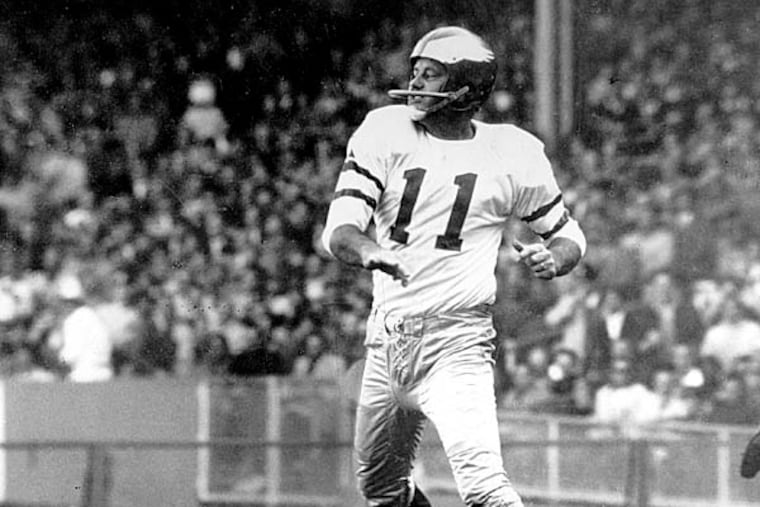

The Dutchman in love: Long-lost letters show Eagles legend Norm Van Brocklin was more than a tough QB | Mike Sielski

He was known as a rock-ribbed he-man among he-men. But a discovery by his daughter shows a different side of the Hall of Famer.

The story began as these stories do: a curious daughter, a drawer sliding open, then a revelation.

In December 1987, not long before the death of her mother, Gloria, Kirby Vanderyt was cleaning out Gloria’s desk, looking for bills to pay and papers to dispose of, when she found a stack of letters knotted together with a lovely little piece of twine.

Her father – Norm Van Brocklin, the quarterback who was the NFL’s most valuable player and the Eagles’ jagged-edge leader during their 1960 championship season – had died of a heart attack, at 57, in 1983. Those who knew or knew of Van Brocklin through his football career saw him in just one dimension: a rock-ribbed he-man among he-men, demanding to the point that his teammates feared him and feared letting him down.

But Vanderyt, 71, the eldest of Norm and Gloria’s six children, knew him as a doting husband and dad. So when she started to leaf through and read the letters, written by her father to her mother when they were young, she wasn’t surprised at their tone and content, though she understood why someone else might be.

She gathered the letters, put them into a box, and kept the box at her house. Then she forgot about them for nearly 30 years.

***

My dearest darling Gloria,

I walk by places where you and I have frequented before or even walked past, and my heart misses a beat and my mind went blank thinking of you. I love you very much, darling, very, very much. More than anything else in the world, honey, even athletics. See you Saturday nite. Missing you terribly. I love you oh! so much!

With all my love,

Stub

***

In the NFL, Van Brocklin was called “The Dutchman,” but “Stub” was his other, more intimate nickname. His mother gave it to him when he was a boy because, though he had large hands, his fingers were shaped like 9-volt batteries. When he bumped into Gloria Schiewe on the quad at the University of Oregon in April 1946, he insisted that she call him that.

» READ MORE: Eagles draft preview: Taking stock of the Eagles quarterback options

She was two years older than he was, a teaching assistant in a biology course he was taking. He was 20 when he met her, but he had lived. At 17, he had forged his mother’s signature at the draft office, skipping his senior year of high school, serving two years in the Navy during World War II, then using the G.I. Bill to go to college.

In Eugene, he was a sixth-string halfback before moving to quarterback, finishing sixth in the Heisman Trophy voting in 1948, and getting drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in 1949.

By then, he was a married man.

***

My darling most precious wife,

Here I am back in town and back to the old grind again. It was hotter than h--- on the field today & I lost 5 more pounds (174). I had to shovel the basement full of sawdust then wash the windows in my room, wax and polish the floor, & then wash woodwork, shower and shave, & then write to my “sweety-face.”

With all my love,

Stub

***

He wrote the letters – 52 in all, roughly one a week, usually every Thursday – throughout 1946 and into 1947, while he was still an undergraduate, while she was working at a hospital in Portland, 110 miles from Eugene and Stub, and contemplating medical school. In December 1946, Stanford offered Gloria admission into its physical therapy program. She turned it down. They were getting married in March. She had made commitments. She would go where his football career took them.

It took them to Los Angeles for nine years with the Rams, then, through a trade, to the Eagles in 1958. The family settled in Valley Forge.

“From a family standpoint, they were just wonderful years,” Vanderyt said in a phone interview. “It was a brief three years, but they were a great three years.”

The third of them, 1960, was Van Brocklin’s last in the NFL and the best of his Hall of Fame career, and no Eagles quarterback, within the context of his respective era of pro football, has had a better one. The team went 10-2, beating Vince Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers, 17-13, at Franklin Field for the franchise’s first championship since 1949, and Van Brocklin finished second in the league in touchdown passes (24), passing yards (2,471), passer rating (86.5), and yards per attempt (8.7). He orchestrated five fourth-quarter comebacks and four game-winning drives; he led all quarterbacks in both categories. Four different voting bodies selected him as the NFL’s most valuable player, and to his contemporaries, the manner and methods of his leadership mattered as much as or more than his play on the field.

Every Monday, for instance, he’d rouse his teammates, most of whom lived in-season at the Walnut Plaza, from their sleep and order them to convene at 10 a.m. at a shot-and-beer bar, Donoghue’s, on Walnut Street. They’d drink. They’d talk football. They’d bond. And all of them, even the team’s top players – Chuck Bednarik, Tommy McDonald, Pete Retzlaff – acknowledged that Van Brocklin was the orneriest and most influential among them.

“You wouldn’t imagine him to be a Hallmark kind of guy,” said NBC Sports’ Ray Didinger, who co-authored The Eagles Encyclopedia. “He was just demanding in the extreme. He didn’t spare people’s feelings and didn’t suffer fools, be they reporters, opponents, teammates, whatever. Very abrasive. Tart-tongued. Profane.”

He was the same way throughout a 13-year head-coaching career with the Minnesota Vikings and Atlanta Falcons. A chain-smoking Nixon man in the age of hippies, he banned his players from wearing bell-bottoms and long hair. He was blunt, sometimes tiptoeing to the plank’s edge of being crude, sometimes leaping off that plank. What did a football player need to be successful? “You have to have it under your left nipple,” he said. His preferred term for newspaper reporters: “whore writers.” He referred to the NFL’s’ California-based franchises as “prune pickers” and a game against one of them as “a Pier Six brawl. For men only.”

Yet those who played for him and covered him knew him to be a different man at home, away from the public, with Gloria and the children – that the sight of little feet under the dinner table soothed the grouchy, cutthroat-competitive side of his personality.

“He is,” one writer said of him in 1973, “the most paradoxical individual I’ve ever seen in sports.”

***

My darling most precious wife Gloria,

I love you my darling. Only a few more days and I’ll be able to see my honey again.

Same old routine down here for me, classes, football & then study at nite; living a christian [sic] life & it is o.k. cause I am staying out of trouble & feel good about it all cause I feel I am doing the right thing. Hope you are also.

Well, honey I have to write my Mother so best I close …

All of me to you honey!

Your boy,

Stub

***

In the fall of 2015, her husband, Bill, having died of brain cancer, Kirby Vanderyt contemplated selling the house where her children had grown up. In tidying up the home, she rediscovered her father’s letters to her mother. At first, she didn’t know what to do with them. They were precious to her. What did they mean to anyone else?

She had taken up writing to deal with her grief over Bill’s death, self-publishing two books. It took her six years, but, using the letters as her inspiration, she published a third, The Dutchman and Portland’s Finest Rose, last year.

Her hope is that the book and the letters will allow the people who saw her father through only one lens to see him through another.

“I think many of us should be so fortunate to stumble across these little gems from our parents,” she said. “Particularly in the times we live in, which are so divisive, we forget the innocence with which we all start when we become young adults. Life takes a hold of you, and your own narrative evolves from there.”