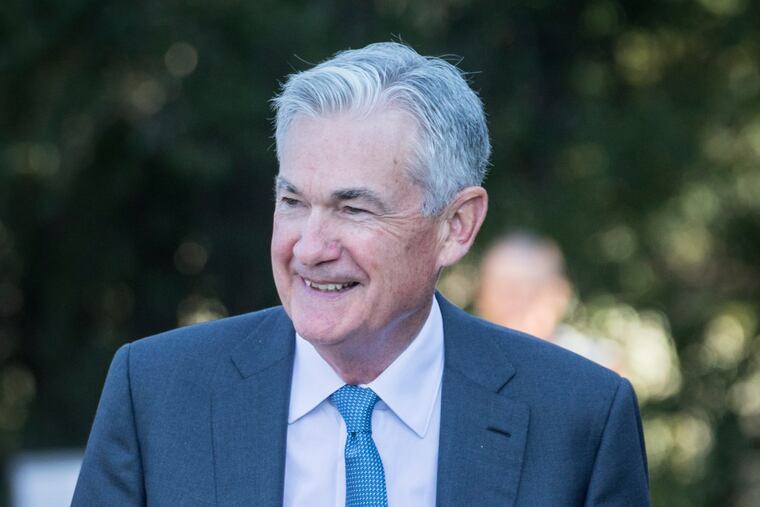

Federal Reserve’s Jerome Powell: Higher interest rates unlikely to cause a deep U.S. recession

The last time the Federal Reserve faced inflation as high as it is now, in the early 1980s, it jacked up interest rates to double-digit levels.

WASHINGTON — The last time the Federal Reserve faced inflation as high as it is now, in the early 1980s, it jacked up interest rates to double-digit levels — and in the process caused a deep recession and sharply higher unemployment.

On Thursday, Chair Jerome Powell suggested that this time, the Fed won’t have to go nearly as far.

“We think we can avoid the very high social costs that Paul Volcker and the Fed had to bring into play to get inflation back down,” Powell said in an interview at the Cato Institute, referring to the Fed chair in the early 1980s who sent short-term borrowing rates to roughly 19% to throttle punishingly high inflation.

Powell also reiterated that the Fed is determined to lower inflation, now near a four-decade high of 8.5%, by raising its short-term rate, which is in a range of 2.25% to 2.5%.

» READ MORE: Interest rates to rise higher, stay elevated longer, top Fed official says

Even so, he did not comment on what the Fed may do at its next meeting in two weeks. Economists and Wall Street traders increasingly expect the central bank to raise its key short-term rate by a hefty three-quarters of a point for a third straight time. That would extend the most rapid series of rate hikes since Volcker’s time.

The Fed’s benchmark rate affects many consumer and business loans, which means that borrowing costs throughout the economy will likely keep rising.

On Thursday, the European Central Bank increased its key rate by three-quarters of a point, the largest in its relatively short history, as Europe also struggles with record-high inflation and a stumbling economy.

Central banks around the world are scrambling to keep up with rising prices. The Bank of Canada on Wednesday lifted rates by 0.75 percentage point and earlier this week the Reserve Bank of Australia implemented a half-point increase.

Despite Powell’s assurances, many economists worry that the Fed will have to allow unemployment to rise much more than is currently expected to get inflation back to its 2% target.

The Fed has projected that unemployment will rise only to 4.1% by the end of 2024 as higher rates bring down inflation. New research released Thursday under the auspices of the Brookings Institution says that such a scenario requires “quite optimistic” assumptions and finds that unemployment may have rise much higher to bring inflation down.

Powell warned two weeks ago at an economic conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, that the Fed’s inflation-fighting efforts will inevitably “bring some pain to households and businesses.” But, he added, “a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.”

Still, on Thursday, he reiterated that the Fed’s goal is to achieve a “soft landing,” in which it manages to slow the economy enough to defeat high inflation yet not so much as to tip it into recession.

“What we hope to achieve,” the Fed chair said, “is a period of growth below trend, which will cause the labor market to get back into better balance, and then that will bring wages back down to levels that are more consistent with 2% inflation over time.”

Other central bank officials have recently echoed Powell’s message.

“We’re not trying to engineer a recession,” Loretta Mester, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, said Wednesday in an interview with the newswire MNI. “We’re trying to engineer a slowdown or moderation of activity.”

At the same time, Mester acknowledged that the Fed’s rate hikes will likely lead to job losses and will be “painful in the near term.”

And Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard, also in remarks Wednesday, pointed out that there are signs that supply chain snarls are easing, which could boost factory output and moderate prices.

In addition, she noted that auto makers and retailers enjoyed hefty profit margins when goods were scarce and Americans were spending robustly. As consumers start to pull back in the face of high inflation, Brainard said, retailers and car companies may have to cut prices to boost sales. That would help slow inflation.

Yet many economists say that as borrowing rates keep rising, employers will cut jobs, consumers will slash spending and a downturn will eventually result. And some have issued starker warnings about the consequences of the Fed’s aggressive pace of rate hikes.

Larry Summers, a Treasury secretary under President Bill Clinton, has said he thinks the unemployment rate, now 3.5%, might have to reach 7.5% for two years to reduce inflation close to the Fed’s 2% target.

The new paper released Thursday concluded that the Fed may have to lift unemployment as high as Summers has suggested to curb inflation. The research, by Laurence Ball, an economist at Johns Hopkins, and two colleagues, found that the pandemic has made the job market less efficient in matching unemployed workers with jobs — a trend that would accelerate unemployment as the economy weakens.

In addition, Americans expect higher inflation over the next few years, the research found. Typically, when that happens, employees demand higher pay, and their employers raise prices to make up for their increased labor costs, thereby fueling inflation. As prices accelerate, the Fed feels pressure to step up its rate hikes, putting the economy at further risk.

Still, not all economists accept that darker scenario. Jan Hatzius, an economist at Goldman Sachs, argued in a note earlier this week that there are “some encouraging signs” that a soft landing is still possible.

Hatzius cited slower economic growth, a decline in the number of open jobs, a downshift in hiring and a drop in the prices of oil and other commodities as factors that could lower inflation in the coming months without necessitating a recession.