From high school dropout to Ivy League student, Penn grad talks about beating the odds in her new book

Aminata Sy graduated from CCP and Penn, then got her master’s at American University.

Aminata Sy was just 10 when her parents sent her from their home in the capital city of the Democratic Republic of Congo to live with a relative in Senegal.

It was supposed to be for a short time, but she never was able to return. She wouldn’t learn until years later that her parents feared she would be raped, a danger that young girls there faced.

But for Sy, who dropped out of high school in Senegal and came to the United States at age 21, already married, it was just the beginning of the traumas and challenges that shaped her life but also led to her monumental accomplishments.

The married mother of three obtained her associate’s degree from Community College of Philadelphia, where she started in remedial classes but eventually mounted a 4.0 GPA. As she prepared to graduate in 2015, she told The Inquirer she had come there, “having a 7-month-old baby, two other children, being married, and having a weak academic background. But by the time I finished my first year, I had this feeling I could do anything.”

She was accepted to the University of Pennsylvania’s College of Liberal and Professional Studies. After obtaining her bachelor’s at Penn, where she met then-Vice President Joe Biden and other dignitaries, she earned her master’s at American University and was accepted into the competitive, prestigious Rangel Graduate Fellowship Program aimed at preparing people from diverse backgrounds for careers in foreign service.

Along her journey, she endured a difficult pregnancy, the loss of a restaurant she and her husband started, and a grueling commute to American, in Washington.

Sy, now 44, was determined to help lift her family economically, and in 2022 began her career as a U.S. diplomat in Brazil, moving her family there.

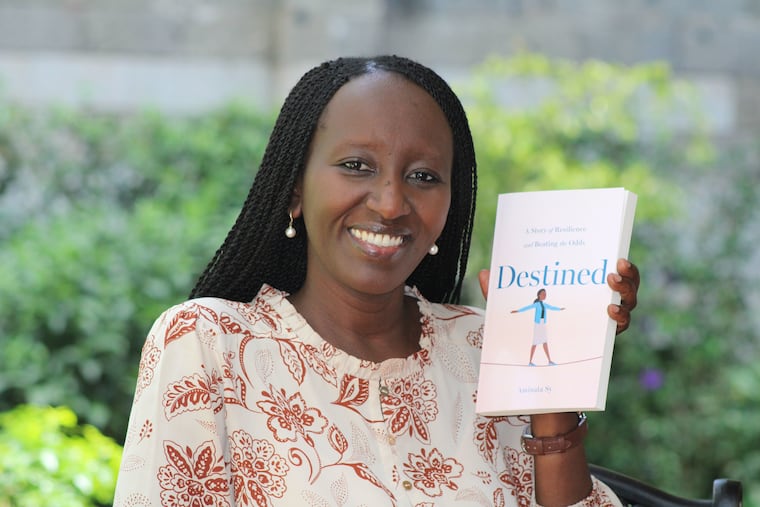

She details her story in Destined: A Story of Resilience and Beating the Odds, her self-published book that comes out Feb. 4.

From Nairobi, Kenya, where she is stationed as a diplomat and lives with her husband and two children, ages 22 and 13 (her third child, 20, attends Temple University), Sy talked to The Inquirer.

She plans to return to Philadelphia in February to discuss her book, with appearances at Blackwell Library, CCP, and Penn.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Why did you write the book?

It was important for me to tell the story because I understand what it is like to struggle. Sharing that, both the struggle and the progress, could be helpful to someone else.

I came to Community College as an English language learner, so at that point, I wasn’t thinking I’m going to write a book. Then as life went on, I continued to grow as a writer. I … eventually moved on to Penn, moved on to American, started in journalism [Sy wrote for the student newspaper, The Inquirer, and the Philadelphia Tribune, among others], worked in nonprofit. I thought maybe I could pull all of these things together in the hopes that it would inspire someone.

» READ MORE: More support needed for students who don’t speak English | Opinion

Just because you are struggling today, that doesn’t mean that’s the end of your story. If you stay at it, you could experience something else that you … never would have imagined in your life.

You overcame many obstacles. Which was the toughest?

If I’m to pick two, I would say separating from my parents as a child was really, really hard for me. If I was to pick a second, it would be raising my kids and trying to go back to school and doing all these other things.

What was it like for you being uprooted from your parents and sent to live with your aunt?

Mostly what I felt was confusion. … I was trying to integrate into Senegalese society and trying to learn the language, trying to learn the culture. It was a lot of confusion, a lot of pain.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia’s many African students need culturally inclusive education | Opinion

Your aunt didn’t have a lot of resources, but years later you really ended up appreciating what she did for you?

It was really a process, living with someone who is struggling to make it and within that struggle trying to help you as a kid growing up. All I could see most of the time was just a struggle. When I left her, I carried a lot of pain, a lot of trauma. But as I became a mother myself, things really started to shift within me. Around 27, I started to think I don’t want to carry the burden of trauma I carried as a kid. I want to forgive, because it’s heavy, and I want to let it go.

It allowed me to see my aunt in a different light, a light of someone who had awesome responsibility in her hands and a woman who tried to do her best with that awesome responsibility but did not have much to work with. This woman was amazing. I literally carry her spirit with me to this day.

Why did you drop out of high school?

I repeated ninth grade twice. I was struggling. I’m showing up … not really understanding anything. My mind feels like it’s blocked. … There is no point. I’m just going to stop.

How hard was it to lose the restaurant you and your husband ran following a difficult pregnancy?

The restaurant was an amazing experience but a short one.

It was visiting your children’s preschool and grade school that reignited your longing for a new start at school?

Absolutely. It felt like a rush of that started coming back to me. Both the desire to learn, the desire to teach. To be better at reading, writing, so I could help my kids. Eventually that evolved into something else.

How did you like CCP?

CCP allowed me to basically drop many of the doubts I had in myself as a student and as an intellectual. Eventually I started reporting for the student newspaper. I was constantly paying attention to local news, national news. That pushed me intellectually to another level.

And Penn?

Penn took me to a whole other level. I got to work with professors who are top-notch in their fields, [be] among the most competitive students in the country. You can’t ask for more. [It’s when she started a nonprofit education program in her basement for children from African backgrounds, which was relocated to a library and then a high school.] Most of the resources that I used were resources I got through connections at Penn or literally from Penn administrators and staff who were following my work and wanted to support what I do. I have nothing but love for Penn.

But you also felt like people didn’t appreciate your husband’s profession as a parking attendant?

The Penn world is a world of big titles. If you don’t have the big titles, then all of a sudden the conversation is not so interesting.

The commute to American University sounded brutal.

I would start at around 5 a.m. and end around … 1 a.m. I was doing it twice a week, but it felt like I was doing it more … because of the fatigue I was feeling. … But I had to live [in Philadelphia] to continue to monitor my kids’ education.

But classes went remote during COVID-19?

It allowed me to stop the commute.

You became a U.S. diplomat in Brazil in 2022, but you didn’t write much about that. Why?

The book was not really about the job. The book was about the journey that got me to the job.

How do you like the job?

As someone who didn’t even grow up in the United States … to go to a point where I am able to represent the country, it’s a tremendous, tremendous honor for me and privilege to do that.