Here’s how this Philly elementary school moved from bare-bones budget to statewide star

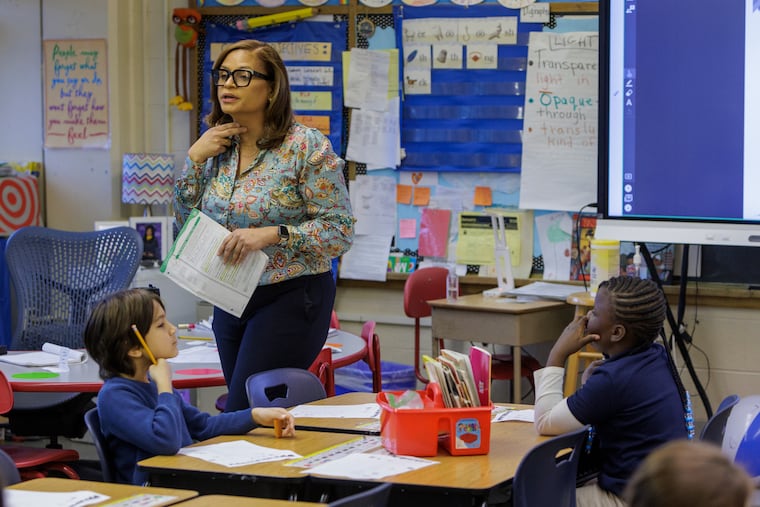

Pennsylvania’s top education official visited a few months ago to highlight the work going on at Lingelbach, in part because of a dramatic increase in student performance as measured by state tests.

When the bell rings, signaling dismissal at Anna Lane Lingelbach Elementary School, kids swarm the new playground in front of the building on Wayne Avenue in Germantown.

The feel-good scene isn’t just a happy end to a day at the Philadelphia public K-8 school. It’s indicative of what is happening inside: Lingelbach has growing and diverse community support, staff who have stayed for decades, and a principal who has led the school for nine years.

Pennsylvania’s education secretary visited a few months ago to highlight the work going on at Lingelbach, in part because of a dramatic increase in student performance as measured by state tests: The percentage of third graders passing English exams jumped a stellar 173%, from 26% to 71%.

Lingelbach, in Germantown, is on the rise.

It’s a major shift for a school that a decade ago made headlines for having a discretionary budget of $160 for the entire school year. In 2014, an Inquirer report described a Lingelbach that was not just financially devastated by state budget cuts, but also academically struggling, lacking resources, lacking technology.

The changes in 10 years are dramatic, but no miracle. Lingelbach moved the needle intentionally, with an enormous amount of hard work from staff and students and the kind of momentum that is making people sit up and take notice.

Stuck in the ‘80s

When Lisa Waddell became Lingelbach’s principal nine years ago, she found “a quaint place, in some great ways and some not-so-great ways. A lot of the things were done the way you might have done them in the ‘70s or ‘80s.”

It was Waddell’s job to advance the school — leaning into strengths and introducing new systems.

Climate became an early focus and remains one, with clear and consistent rules, high expectations, and strong supports. Waddell knows everyone’s name, their families and their struggles.

“We can’t solve all of those things, but we’re aware, and we find resources when we can,” Waddell said. The primary role of Kara Yanochko, the dean of students, is not discipline but social-emotional learning; on a recent day, Yanochko spent time teaching lessons about relationships in a class that had some conflicts.

Tim Riley teaches math and science to the school’s oldest students, and has worked at Lingelbach for 15 years. The changes in the school are marked, he said.

In the past, Riley said, he might spend 60 minutes of a 90-minute instructional block teaching; the rest of the time was spent handling classroom issues, counseling a student, or addressing student behavior.

“Now, we work from bell to bell — we teach for 90 straight minutes, without distractions,” Riley said. “There aren’t kids in the hallways anymore, there aren’t kids in the bathrooms. Kids are positive, they get here early.”

Years ago, Judy Brody was the regional superintendent responsible for Lingelbach. Now, the retired educator, who also taught at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, is back as a community member supporting Lingelbach through its friends group.

Waddell, she said, is the best kind of principal.

“She understands systems, understands that connecting with people and community is what is so important. She doesn’t dictate, she works collaboratively. She’s the crème de la crème,” said Brody.

A reading pivot

Erin Serock thought she was a strong second-grade teacher.

Then she took a class on teaching reading at AIM Academy in Conshohocken. Serock, like a generation of teachers, was taught in college that the best way to instruct children to read was through a so-called balanced literacy approach, which stressed providing students with books that interest them and giving them ample time to read. It held that students learn to read relatively naturally, and de-emphasized phonics instruction.

But a growing body of research holds that’s wrong, that teaching phonics, foundational skills, systematically — the science of reading — is the way to go. Serock left the AIM class convinced, too, and she told her principal.

“I said, ‘We’re doing things all wrong. We could be doing so much better for these kids,’” Serock remembers. Waddell was on board right away. The principal took the course herself and found the funds for every Lingelbach K-2 teacher to do the same.

Lingelbach began using science of reading methods just before the pandemic and persisted through it.

Serock, now a school-based teacher leader, analyzes all K-2 students’ data: Who doesn’t know their letter sounds? Which sounds are they missing? Serock writes a plan for each, and they get one-on-one instruction not when busy classroom teachers can find the time, but daily, from the school’s support staff, all of whom are trained in the research and coaching students on reading.

“They might work on ‘B’ five days a week for five minutes,” Serock said. “Each individual student gets exactly what they need.”

The results have been dramatic. That jaw-dropping third-grade state test growth? That belonged to the first Lingelbach class to receive science of reading instruction from kindergarten on.

The gains continue. Until a few weeks ago, fourth-grade teacher Rebecca Hoffman had 35 children in her class — a second teacher was recently added, and her class halved — but even with her room bursting for months, it’s been “one of my best years in teaching, ever,” Hoffman said.

She’s not catching students up, she’s zooming through fourth-grade work.

“Not only is it affecting their reading and their writing and speaking and listening, it’s affecting all of the subject areas,” said Hoffman. “They can grapple with fourth-grade material.”

Harnessing the outdoors

Though Lingelbach sits on busy Wayne Avenue, the school backs into a wooded area that runs all the way to Lincoln Drive. For years, Riley, the middle school math and science teacher, worked with what time and resources he could scrounge up to turn the space into an outdoor classroom. But it was an uphill battle in an under-resourced district.

Kids, teachers and parents also dreamed of a playground after years of only patchy concrete in front of the school.

But as things began clicking into place at Lingelbach, help started to materialize. A Friends of Lingelbach group formed, galvanized by a skilled, welcoming principal and the staff and families she served. That group, with its mix of parents and community members, had the time and expertise to raise funds.

It took five years and a partnership with the Trust for Public Land, but Lingelbach’s playground opened last spring. Grants also helped build a forest classroom with zipline, benches, a playhouse, and more, and children in Lingelbach’s lower grades now receive nature lessons outside through a Forest Days program.

It’s a wonder to Riley, who gives students in the older grades outdoor time, too, so the whole school has a chance to experience the trails, the butterfly garden, the pollinator garden, the red-tailed hawks, foxes, deer and owls. Learning geology while standing in the Wissahickon just hits differently.

“The kids are knowledgeable about the natural environment, and that’s a huge shift,” Riley said. “When I started here, kids viewed the outdoors as a scary place.”

Diversify, not gentrify

A decade ago, 88% of Lingelbach’s students were Black, and 1% were white. These days, 75% are Black (compared with 43% district-wide) and 16% are white (compared with about 15% across the district), with more diversity in the younger grades.

The school now “is more representative of the streets and the neighborhoods that we live in, more so than it has been in the past, and that’s brought nothing but positives overall,” said Yanochko, the school’s dean.

It’s a marked difference from decades ago, when it was time for Peggy Bradley to enroll her oldest in kindergarten. She walked from her home on Harvey Street to Lingelbach, and the principal looked at Bradley and told her that white families generally felt more comfortable at Henry, a public school in Mount Airy.

“I was aghast, but I talked to my neighbors on Harvey, and they said, ‘You should listen to her,’” said Bradley, who ultimately did. Now, Bradley is the ESL teacher who loves working at Lingelbach, a full-circle moment.

Waddell is keenly aware that changes to Lingelbach could minimize or exclude the Black families who have sent their children to the school for decades.

“We don’t want to become a school that doesn’t look like the school that once existed,” said Waddell. She is intentional about equity, about community events that work for everyone, and sometimes, that means saying no to such things as a big donation from a single Lingelbach family who can afford it.

“I don’t want it to become about, ‘Who has the power? Who can give when someone else isn’t able to give?’” said Waddell.

Parent Shani Depte is pleased with the education her fourth grader, Mason, is receiving at Lingelbach — he loves science and has made good friends at the school that’s just a block from their house.

Depte also feels good about Lingelbach’s efforts to reach its community. There’s been a family movie night, and a picnic to celebrate the playground opening — events that helped her connect with other families and built a sense of belonging. She’s seen “an increase in people trying to move to this area to start going to this school,” said Depte. “There’s a tremendous difference, even in the past two years.”

And while more white families are choosing Lingelbach, it doesn’t feel like an us-or-them situation, said Depte, who is Black.

“It’s more diverse, more of the community,” said Depte. “It’s not, ‘Now they’re here, you can go.’”

Goals still to reach

While Lingelbach’s academics are strengthening, it still has a ways to go: while its third-grade English scores were strong, school-wide, only 40% of students passed state English exams and 20% math tests.

Waddell would love for Lingelbach to be known as a science school, but it doesn’t have the resources for a full-time science teacher, and must raise money year to year to keep its forest education curriculum going.

She also dreams of hiring more adults to staff recess, to support students’ social and emotional needs.

But there’s a sense of optimism.

“We will always work with staff and families to use what we have to get the best outcomes for students,” Waddell said.