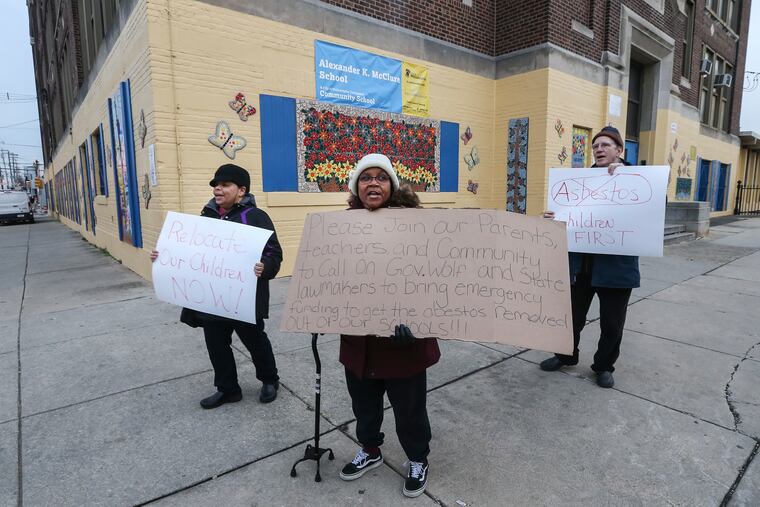

‘We’re struggling’: McClure Elementary parents cope with the practical fallout from Philly’s asbestos crisis

“We’re pulling our hair out, we’re struggling,” said Jessika Roche, whose son, Cassius, is in third grade at McClure, which is currently closed as officials tackle areas of damaged asbestos throughout the building. “It’s taken a huge toll on our family.”

Jessika Roche doesn’t want her 8-year-old back inside his school until all asbestos is removed from McClure Elementary in Hunting Park.

But the Philadelphia School District’s asbestos crisis has raised immediate, practical concerns beyond her and other parents’ fears for their children’s long-term health.

As in: What do you do with your child or children when they’re unexpectedly out of school for the better part of a month, as Roche’s son and other McClure students have been?

“We’re pulling our hair out, we’re struggling,” said Roche, whose son, Cassius, is in third grade at McClure. The school is closed as officials tackle areas of damaged asbestos throughout the building. “It’s taken a huge toll on our family.”

McClure, a K-5 school with over 600 students, was first closed on Dec. 19; it reopened for two days in January before being shut again when air tests revealed elevated levels of asbestos fibers.

Students were expected to return immediately after the winter break, but the asbestos contamination was worse than expected. Children returned to class for two days last week, but the school was abruptly closed again when new damage was found.

On Monday and Tuesday, McClure students will not be in classes, but they will be able to go on district-paid field trips, district spokesperson Megan Lello said Friday evening. Parents must pick up their children by 1:30 p.m., however.

“We’re doing it in an effort to keep instruction going in some way, shape, or form,” said Lello.

In all, six district schools and an early childhood center have had to close this school year because of asbestos; officials began paying closer attention in September, when news of a career Philadelphia teacher’s mesothelioma became public.

» READ MORE: Read more: She taught in Philadelphia schools for 28 years. Now, Lea DiRusso has mesothelioma.

In some cases, like those of Benjamin Franklin High School, Science Leadership Academy, and T.M. Peirce Elementary, students were eventually relocated while work on their buildings continued. McClure students have simply missed a lot of school.

Lello said a plan to have McClure students make up some lost instructional time is being developed and will be shared with the Pennsylvania Department of Education, which mandates 180 days of instructional time per school year.

“It does not look like the other schools will need to make up days,” said Lello. McClure students were not given packets of work to do while out of classes, as the closure was not planned.

» READ MORE: Read more: Under pressure, the Philadelphia School District touts a new environmental plan

Roche considers herself lucky. Her work, driving for rideshare companies and delivering food orders, is flexible, so she’s been able to shift her schedule to stay home with her son during the day. But it’s meant that Roche never sees her husband, as she has to rush out the door to start working the moment he comes home from his job.

Plus, there’s the boredom factor. Some parents are teaching kids what they can, via workbooks or free online resources, but that’s no substitute for the instruction children receive in school.

“We have nothing to do with these kids; I can’t afford to spend $50, $60 to take them places,” Roche said. “It’s cold, so they can’t go outside to play.”

Some McClure parents have banded together to watch each other’s children to cover work shifts. Jasmine Santiago has had to come up with another solution.

Santiago works as a teacher’s aide at McClure. When staff were required to report to another building despite the school’s closure, she was forced to send her two kids, who are McClure pupils, to live with her mother in Delaware for days or a week at a time.

“That’s my only child-care option,” said Santiago. “I have to go to work.”

Rosalind Lopez, whose grandchildren attend McClure, fears what the lost instruction time will mean for students.

“Will they all have to repeat a grade?” said Lopez, who has gathered signatures on a petition to demand that McClure not reopen until asbestos cleanup is complete. “This could hurt them.”

Kindergartner Jsaah Bing knows why he’s out of school: There’s bad stuff there, stuff that could make him and other kids sick.

“But I’m not happy to be home,” said Jsaah. “I want to go back to school.”

Veronica Bing Perry, Jsaah’s grandmother, won’t send him back until she believes the school is safe. But she worries about Jsaah, who has special needs, missing school.

“He has an IEP that’s not being met. I had just signed him up for more services at the school,” said Bing Perry. “I go online and I look up what he should be doing, and I just give him a little bit at a time to do, but it’s hard. It’s hard for all of us caregivers.”

Bing Perry’s other grandchildren attend schools in Upper Merion and Radnor. She can’t help but wonder what would happen if damaged asbestos was discovered in one of their schools.

“If anything was to go wrong in the suburbs, it would be taken care of, right away,” said Bing Perry. “Because we’re in a lower-income community, we get pushed to the side.”

McClure’s closure has even affected some local businesses.

Danielle Evans, a co-owner of Stages Community School, at first saw more business at her day care, which enrolls a number of McClure students for before- and after-school programs.

At first, Evans allowed families to keep their children at the center for the full day, though state funding only covered part-time care. But as the closure dragged on, Evans and her business partner had to charge an extra fee, to cover the extra staff they had to pay. A state official said Pennsylvania wouldn’t pick up the extra charge, Evans said.

“My business is definitely suffering,” said Evans. “Some parents are leaving, trying to get their kids in charters; some parents are saying they’re going to homeschool.”

Evans, too, wonders if things would have been different if the asbestos crisis had happened outside of Philadelphia.

“It’s just ridiculous that they kept the children out of school this long and have no resources for the parents that don’t cost additional money,” Evans said. “It’s not fair, it’s not safe.”