With Cabrini University closing, where will all their professors go?

The president estimates more than half of the more than 360 employees have found jobs.

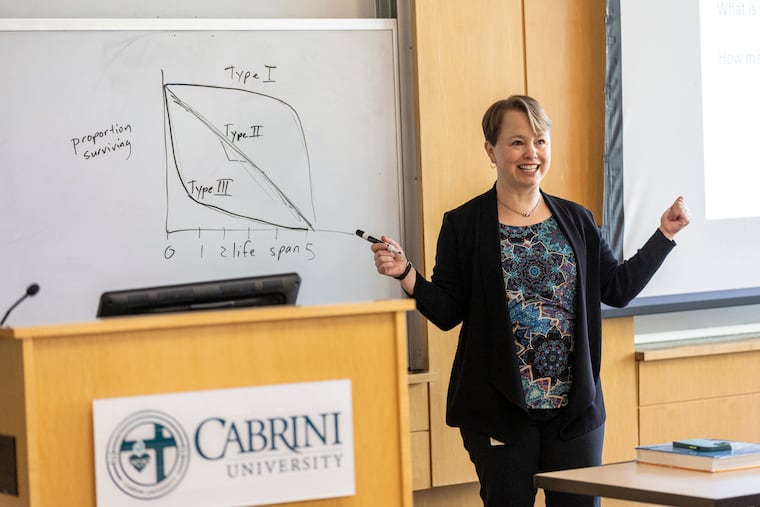

Carrie Nielsen, a professor of biology and environmental science, has taught at Cabrini University for 16 years.

It’s where she thought she’d work the rest of her life. Even after retirement, she envisioned still teaching a course there, just as her psychology professor grandfather did in his later years at Kalamazoo College in Michigan.

“Be part of the life of this institution until I die,” she said. “And then they would plant a tree on campus with a little plaque and my name on it.”

» READ MORE: Villanova finalizes agreement to acquire Cabrini University campus

But Cabrini, it turns out, will be making its exit before her. After 67 years, the Catholic university will close for good June 30. Nielsen and many of her faculty colleagues got the shock of their lives last June when the decision was announced, and since then have been searching for their next steps, both in and outside of higher education.

At 48, Nielsen knew that her life and family are rooted in the area, so she needed something local.

“There’s only been a small handful of positions [in higher education] that somewhat align with my background,” she said.

It’s been challenging for Nielsen and some of her colleagues, especially those in their mid- to late careers, who have had to contemplate whether they can or want to stay in higher education. The job market for faculty has always been tight and getting tighter as enrollment falls at many colleges, which then have to make cuts.

» READ MORE: With stats stacked against them, students get help from soon-to-close Cabrini University to enroll elsewhere

“It’s kind of forced a bunch of us to make some life decisions, whether we are ready for them or not,” said Melissa “Missy” Terlecki, the associate dean for the School of Arts and Sciences.

Where are they going?

At Cabrini for 19 years, Terlecki moved up through the ranks, from assistant professor to associate to full to chair and finally dean. She hadn’t any plans to leave.

But she landed a dean’s job at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. Starting July 1, she’ll lead the School of Professional and Applied Psychology.

“I’m excited for the opportunity,” she said. “Certainly, I’m sad that we are closing.”

Cabrini president Helen Drinan said that she has been pleasantly surprised at the success many administrators and faculty, such as Terlecki, have had finding new jobs. Some have already left for other positions. While the college has no firm count, Drinan estimated that more than half have been successful.

» READ MORE: As Cabrini begins its final year, remaining students note a smaller campus. Where did the others go?

A handful, she said, are going to Villanova, which is buying Cabrini’s campus when it closes. A group, including several communication professors, will head across the street to Eastern University. Johns Hopkins University, Sacred Heart University in Connecticut, and Kutztown University are among other destinations.

More than 360 employees, including full-time faculty, are expected to lose their jobs over the next six weeks, according to a notice Cabrini filed with the Pennsylvania Department of Labor. Drinan said that when adjunct professors and students who also work at the college aren’t included, the number impacted is less than half. Cabrini started the year with 54 full-time faculty, and four left mid-year.

Faculty have been told to expect a layoff Monday, the day after commencement.

Getting the resume ready

Cabrini brought on a team that offered job-seeking support to employees, including how to develop a strong resume and LinkedIn profile, tips on interviewing, and ways to explore new opportunities. The coaches provided one-on-one counseling.

Kimberly Boyd, dean for retention and student success, said she met with a coach weekly and it really helped.

“I had no LinkedIn presence, and they are working with me on that,” she said. “My coach has been really good at asking good questions so I can come up with decisions that meet my passions and talents.”

A cell and molecular physiologist, she considered looking for a science job in pharmaceuticals. Johnson & Johnson has a reintegration program for scientists who have been out of the field for a while, she said.

But she applied for several faculty positions and was offered all of them. She sat with a spreadsheet, contemplating the pros and cons of each.

In the end, she decided to return to teaching, with the hope of using all she’s learned in her administrative role in her own classroom. She accepted a professor’s job at Delaware County Community College, where she’ll teach anatomy and physiology.

Melinda Harrison, science department chair and professor of chemistry, looked for a faculty job but found that she was overqualified for entry-level positions. Harrison, who has worked at Cabrini for 16 years, serving the last six as chair, said she got a couple of offers but nothing comparable to her current position.

Now, she is eying a move to the federal government, where she would work in the science field. Because she doesn’t yet have the position finalized, she declined to be more specific.

She said she looks forward to trying a new career, but will miss being in the classroom.

“I love teaching,” she said. “All of us at Cabrini, we stayed because we love it.”

Nielsen, who has her doctorate from Stanford and environmental science degree from Brown University, got her first tenured-track position at Cabrini. And she’s been happy there.

She focused her search on small liberal arts colleges where the emphasis would be on teaching rather than research. Given her husband’s job and their affinity for the area — “my kids are in Radnor public schools and we love our neighborhood and church” — she applied for a few jobs locally and didn’t get them.

“I had to do some soul searching,” she said.

Nielsen eventually turned her attention to K-12 education.

“Everyone tells me there’s a real shortage of high school science teachers,’ she said.

She also worked with a career coach provided by Cabrini, who helped her turn her curriculum vitae into a solid resume.

Last month, it paid off.

She got a job teaching high school biology and environmental science at Episcopal Academy in Newtown Square.