They just reached a milestone that took some 40-plus years to achieve: high school graduation

More than 1 million people drop out of high school annually, and those who do earn $200,000 less than high school graduates over their lifetime, and $1 million less than college graduates.

Mohamed Elbahwati thought he wasn’t cut out for school.

In 2019, Elbahwati dropped out of Pottstown High two months shy of graduation as he struggled with depression, anxiety, and the lingering effects of a concussion. He spent five years grinding out a living at various jobs and worried, sometimes, that would be his fate forever.

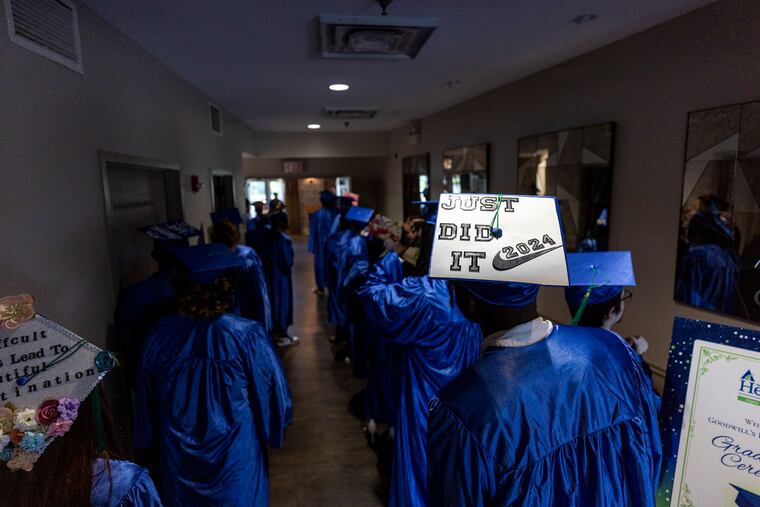

But on Thursday, Elbahwati, 23, stepped to the front of a festively decorated ballroom decked out in a royal blue cap and gown to collect his diploma and an award for best adult learner.

“This is something to be proud of. This was my goal: completing something, being proud of it,” Elbahwati said. “I wanted to get ahead, I wanted to live a stable life.”

Elbahwati was one of 67 graduates of Helms Academy, the Goodwill Industries of Southern New Jersey and Philadelphia program that gives adults a free, flexible pathway to earning high school credentials, and the academic support to get there.

For Mark Boyd, CEO of the regional Goodwill, the joyful ceremony was the distillation of what Goodwill is about: Helms Academy is the nonprofit’s flagship program, he said.

“We are the place that you drop off your gently used stuff, and where you shop, but our mission has always been about helping people realize their economic potential,” said Boyd.

More than a million people drop out of high school annually, and those who do earn $200,000 less than high school graduates, on average, over their lifetime, and $1 million less than college graduates. With funding for adult education programs dwindling, Boyd, his staff, and board wanted to create opportunities to level the playing field, Boyd said. The program, named for Goodwill founder Edgar J. Helms, now operates in multiple locations in Philadelphia and South Jersey.

“We’ve created the new night school,” said Boyd. “Flexibility is our middle name — we will do anything to help somebody get through this program.”

‘My biggest mistake was believing I couldn’t be helped’

Elbahwati hadn’t been out of school that long, but Stanley Fischer’s gap between high school and diploma was 40 years wide. He left Roxborough High in Philadelphia in 1981, when he joined the Army. He built a career in the military, and working in oil fields in Western Pennsylvania.

When knee and back injuries halted his ability to do physically intensive work, Fischer, 61, was at loose ends. Eventually, he researched GED programs and found Helmes. His daughters all had college degrees; it was time for him to collect his high school diploma.

“I always put education first in my home, and I promised my mom that I was going to get my degree, and I’m going to keep my promise,” Fischer said. It wasn’t always easy — Fischer has already had three knee operations and needs surgery on his back.

“I’m in pain all the time, but that never kept me from going to class,” he said. The four-decade gap between his last high school class at Roxborough and his first at Helms was also tough at times, Fischer said.

“As we get older, we get frustrated more easily,” said Fischer. Math class proved especially tough — “it’s the angles and things like that, this new math.”

Fischer studied for two weeks for his final test, but failed by one point.

He was devastated, but his teacher wouldn’t let him wallow. They reviewed the material again and again, and Fischer retook the test — and doubled his score. He spoke at graduation on Thursday, too, and proudly told the audience that he’s been accepted to Peirce College, where he’ll study computer technology.

“Life happens,” said Fischer. “But it’s important that we never lose sight of our dreams and goals.”

Elbahwati, too, is college bound, with an e-sports scholarship to Arcadia University. (Elbahwati is a skilled gamer; his specialty is the video game Overwatch.)

He will also study computer science, and hopes to someday create the games he plays.

“I’ve made mistakes,” Elbahwati said. “My biggest mistake was believing that I couldn’t be helped.”