Judge orders school districts be notified in ‘momentous’ N.J. desegregation case

The judge also will give the state a chance to present experts to respond to the complaint filed by a coalition of civil rights advocates and students, which alleges New Jersey is maintaining one of the nation's most segregated public school systems.

A judge on Friday ordered plaintiffs suing New Jersey over persistent school segregation to notify every district of the lawsuit so they can take part in a case she acknowledged could reshape education statewide.

Superior Court Judge Mary Jacobson in Trenton also said she wanted to give the state a chance to present experts to respond to statistics in the complaint filed in 2018 by a coalition of civil rights advocates and students, which alleges that the state has been “complicit” in maintaining one of the nation’s most segregated public school systems.

“This is a very significant and far-reaching case,” that “merits very careful consideration,” Jacobson said at the end of Friday’s hearing. She said she would not reach a “momentous” decision about the state’s liability without considering the circumstances surrounding the racial gaps among districts.

The suit lays out the racial imbalance among districts statewide — noting that a significant and growing number of black and Latino students attend schools that are almost entirely nonwhite, even though their numbers and that of white students are nearly equal statewide.

» READ MORE: N.J. schools among 'most segregated' in nation, suit says

It faults the state for requiring students to attend schools in the districts where they live and not taking steps that could reduce segregation, like consolidating districts.

The court is considering how to move forward with a case after settlement talks were unsuccessful.

» READ MORE: N.J. school segregation lawsuit inches toward trial after negotiations stall

Jacobson denied a motion by the state to dismiss the case for failing to name New Jersey’s school districts as parties, saying that while constitutional cases can affect “millions of people,” that doesn’t require those people to be part of a lawsuit. She also noted how “unwieldy" the inclusion of the more than 500 districts in the case would be.

But “I am concerned that we don’t have any school districts here" that could provide information important for the court to consider, Jacobson said. She required plaintiffs to send notices of the litigation to New Jersey districts and charter schools — which the lawsuit alleges have contributed to segregation — and set a March 20 deadline for districts to file motions to intervene. The nonprofit New Jersey Charter Schools Association already has intervened.

The judge also ordered both sides to move forward with discovery in the case — disagreeing with plaintiffs that statistics provided enough evidence for her to rule on the state’s liability.

Assistant Attorney General Melissa Dutton Schaffer said the feasibility of any remedies should be considered before finding the state liable. "There needs to be consideration of the entire picture,” she said.

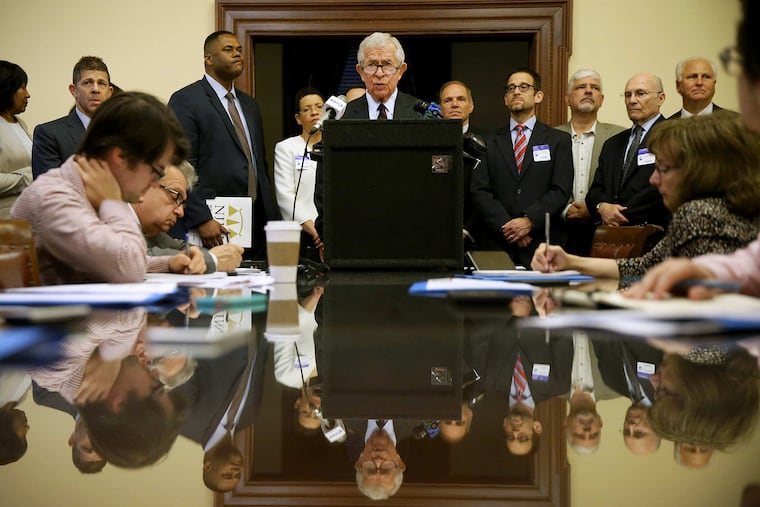

Larry Lustberg, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, argued that it would take a court order to get the state to address the issue.

“There is really no person of intelligence or goodwill who believes there is not a problem,” he said after the hearing. “The real question is, what do we do about it?”

The state and plaintiffs — who include the Latino Action Network and NAACP New Jersey State Conference, among other advocacy groups — have agreed on the statistics that are the basis of the lawsuit.

In 2016-17, almost one-quarter of black public school students in New Jersey attended schools that were more than 99% nonwhite, with another quarter attending schools that were 90% to 99% nonwhite, according to the suit. It said Latino students were similarly segregated, while white students were concentrated in schools that were majority white.

The suit also alleges socioeconomic segregation of students, an issue New Jersey courts have not previously addressed.

Unlike many states, New Jersey explicitly bans racial segregation in its constitution. New Jersey courts have ruled that the state has power to consolidate districts to achieve racial balance.

Jacobson noted that past court rulings have focused on individual or small groups of school districts.

The lawsuit is “a very broad challenge,” she said, seeking to upend the assignment of students to schools solely based on district boundaries. She indicated she was open to the state’s argument that potential remedies needed to be considered in assigning liability.