Pennridge educators warn they aren’t ready to teach a curriculum crafted by a Hillsdale College-connected consultant

The new social studies courses scale back on Native Americans to make room for the Constitution and Colonial America.

As school starts Monday, some teachers in the Pennridge School District have warned they aren’t prepared to teach a new social studies curriculum, revamped this summer with the help of a consultant tied to a conservative Christian college.

The curriculum, written in part by consultant Jordan Adams, lists Hillsdale College’s “1776 Curriculum” as a “required” resource for teachers — spurring outrage from community members who have accused the Republican-led school board of seeking to whitewash history and steer children into a conservative worldview.

Meanwhile, teachers told the board this week that they didn’t have enough time to prepare to teach brand-new units like Colonial America, the American Revolution and the Constitution — added to the elementary school curriculum at Adams’ direction. (To make room for the new material, the district is scaling back on lessons about Native Americans and Pennsylvania.)

“To be honest, I can feel a little panic setting in,” Melinda McCormick, a fifth-grade teacher, told the board at a meeting last Monday. McCormick said she’d never taught some of the topics in the new course — which includes a focus on the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln — and had she known of the changes earlier, “I would have spent many hours over the summer building my own background knowledge.”

The board, which is slated to vote on the new courses Monday night, has been embroiled in controversy over its moves to reshape curriculum. After voting in December to reduce social studies requirements at the high school, the board moved to incorporate the Hillsdale curriculum.

The 3,200-page curriculum, available for free online, has been pushed by the college amid conservative opposition to equity efforts and the New York Times’ 1619 Project. But historians have criticized it as ideologically driven; Princeton historian Sean Wilentz told The Inquirer the Hillsdale curriculum “fundamentally distorts modern American history into a crusade of righteous conservative patriots against heretical big-government liberals.”

The Pennridge board hired Adams, a Hillsdale graduate and former employee of the college, over the objection of the district’s superintendent, who has since gone on leave and will retire in October. The district was the first in the country to tap Adams’ nascent Vermilion Education company, agreeing in April to pay him $125 an hour to review and develop curricula.

He issued his first recommendations in June, drawing pushback from the district’s curriculum supervisors. For instance, Adams — who isn’t certified to write curriculum in Pennsylvania, dissenting board members pointed out — had proposed teaching the Ancient Near East to first graders, spurring questions about where the district would find materials to teach that topic to children that young.

That topic doesn’t appear to be part of the curriculum before the board for approval Monday, which the supervisors and Adams collaborated on. But Jenna Vitale, the social studies supervisor, told the board last week she disagreed with some other changes Adams had made, as well as the push to remake the curriculum as the new school year neared.

Teachers deserve “more than a week to turn this around” Vitale said, adding. “I’m honestly very nervous about that.” She said the third- and fourth-grade courses were “a big change,” and that time was needed to “ensure it’s the right thing for our students.”

Vitale said, “I’ve had concerns about this all along.”

“Well, I haven’t heard any of them,” said board member Megan Banis-Clemens.

“I spoke with Jordan Adams about them. Because that’s who I was working with,” Vitale said.

Adams — who addressed attendees at the Moms for Liberty conference in Philadelphia earlier this summer and described himself as the “fox inside the henhouse” of school districts — didn’t appear at the meeting last Monday. More than 1,600 people have signed a petition online calling for an end to his contract.

Banis-Clemens accused Vitale and the other curriculum supervisors of “dragging their feet,” while Jordan Blomgren, a board member who teaches in a different district, said it was “common practice, where things are rolled out before the school year.”

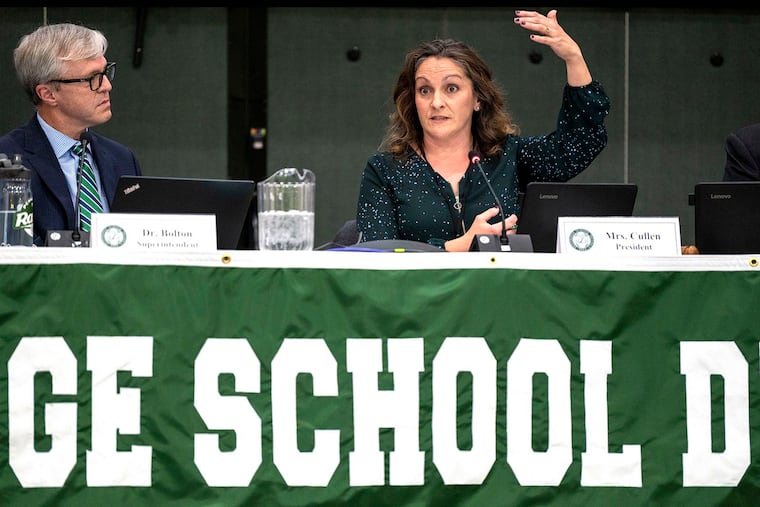

The board has been divided on the Vermilion contract and curriculum changes — splitting 5-4, with Republicans on both sides of the issue. Joan Cullen, one of the dissenting board members, said it made sense for Vitale to speak out during a school board meeting, given that her and other supervisors’ jobs had been threatened by the board earlier this year.

“They’re safer here in telling us what is really going on,” Cullen said, as Banis-Clemens argued that the board hadn’t been trying to punish the supervisors.

Vitale and Adams worked through three units of the new ninth-grade civics, government and economics curriculum, but “it got difficult on the last two units,” said Kathy Scheid, an assistant superintendent. Administrators wanted to incorporate history, but Adams “told me there was to be no history put in this course,” according to Vitale.

Scheid said that ninth-grade teachers could start the year teaching the first three units while the district worked to finish the course.

Underlying the conflict was disagreement over the Hillsdale curriculum, and to what extent teachers would have to use it. As she presented the social studies courses, Vitale said that while the 1776 Curriculum was listed as a “required” teacher resource, teachers would still have discretion as to how they used it.

If that’s the case, asked Jonathan Russell, a board member opposed to Vermilion, why was the curriculum described as required?

“You’re using it as a framework,” Blomgren said, adding that if it wasn’t listed as “required,” then “no teacher is even going to look at it.”

Almost all of the community members who addressed the board opposed the curriculum changes. Some said they were troubled by what they had read in the Hillsdale curriculum.

Hillsdale’s curriculum for third to fifth graders refers to Jamestown’s “original experiment with a form of communism,” which “helped produce a disastrous first year and a half for the fledgling settlement,” noted Stephanie Regina, reading from the curriculum.

Besides the fact that most children that age “don’t know what communism is,” Regina said, “It wasn’t communism.” (The idea that pilgrims embraced capitalism after failing at socialism has been spread by conservatives, but historians dispute it.)

“You can tell the kids, this was a wonderful spirit. Or you can tell them this was evil capitalism,” Regina said. “Or you can just tell them what happened, and they can decide for themselves.”