Pa. schools won’t be required to adopt the ‘science of reading’ next year

Parents and advocates have been pushing for districts to adopt structured literacy, which favors more explicit, systematic instruction. But a measure to mandate it is on hold.

Despite calls from advocates to reform the way Pennsylvania schools teach kids to read — and numerous other states’ having already passed similar legislation — the budget deal last week included no requirements for districts to shift literacy instruction.

Legislation that would have required schools starting in 2025-26 to use “evidence-based” reading curricula, train teachers in structured literacy — an approach that emphasizes explicit instruction in skills such as phonics — and screen all children in kindergarten through third grades for reading deficiencies wasn’t among the many measures in a state budget filled with new education initiatives. The changes were estimated to cost $67.5 million, according to one of the bill’s sponsors.

Because the changes will cost money, lawmakers will have to wait until next year’s budget cycle to pass new requirements for reading instruction, said the sponsor, Rep. Jason Ortitay (R., Washington).

“I think it wasn’t just high enough on the priority list,” Ortitay said in an interview this week. “I’m going to have to get my colleagues in the House and administration to see the light of how important this is.”

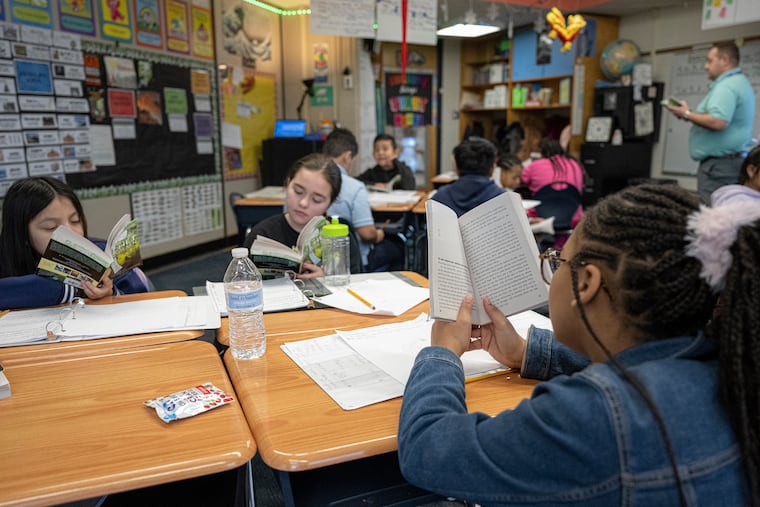

Parents and advocates have been pushing schools around the region to embrace the science of reading — a term that refers both to a body of research into how kids learn to read, and an approach to reading instruction employed by schools. Experts say many children require systematic, explicit instruction in order to “crack the code” of reading.

Yet for years, the philosophy underpinning many schools’ instruction has been that children can learn to read relatively naturally. The approach derived from that theory, balanced literacy, focuses more on independent reading than skills instruction.

Growing attention to the disconnect between reading research and schools’ teaching practices has propelled a science-of-reading movement that has won support from groups such as the NAACP — which has framed literacy as a civil rights issue.

But advocates say students of all racial and socioeconomic backgrounds are affected by inadequate reading instruction. Nationally, 33% of fourth graders were proficient in reading last year, according to national testing data.

Without state requirements for structured literacy — and funding to meet them — “Pennsylvania students will continue to suffer from non-evidence-based teaching methods and curricula, perpetuating existing unequal literacy outcomes,” said Kate Mayer, a literacy advocate who cofounded a group called Everyone Reads PA and works with families around the Philadelphia region. She characterized many schools as operating under a “wait-to-fail model” — waiting for students to fall behind in reading before providing adequate instruction.

‘All on their own to pick whatever they want’

A spokesperson for House Majority Leader Matt Bradford said that Democrats “made it a top priority to fulfill our constitutional and moral obligation to fund our public schools, resulting in a bipartisan budget that puts a record $1.3 billion more in our schools.”

“Because structured literacy is so important, we ensured that these programs are an approved use of funds,” said the spokesperson, Elizabeth Rementer, referring to language allowing districts to use funding for structured literacy. “School districts know their students best and they have the ability to use their funds for these types of programs.”

In recent years, numerous states have passed science-of-reading laws intended to change instruction across the board. Ohio and Wisconsin, for instance, have required districts to choose from a list of approved reading curricula, and banned instructional practices that encourage children to guess words based on context clues, rather than decoding them.

The efforts have met with pushback, including around curriculum mandates and what reading programs qualify as evidence-based. The Pennsylvania bill was softened to allow districts to submit programs to the state Department of Education for review if they didn’t want to choose from a list of approved curricula.

Part of the Pennsylvania bill’s anticipated cost would cover the state’s expanded role in overseeing curricula — creating a literacy council to select recommended vendors and curricula. The money would have also gone to districts to buy new curricula and train teachers, Ortitay said.

Despite the state’s inclusion of structured literacy as an “approved use” for certain funding, Ortitay said districts won’t be required to report to the state on their reading instruction.

“Right now, we have no idea how many school districts are actually using structured literacy,” he said. “There’s no accountability. There’s no transparency. And the school districts are basically all on their own to pick whatever they want.”