Philly schools could be on the forefront of using AI. Here’s what that means.

The district already has guidelines in place, but “Pioneering AI in School Systems,” scheduled to begin in March, will train staff in best practices and possible risks.

The Philadelphia School District is launching a pilot program to train teachers and administrators on how best to integrate artificial intelligence in city schools, an initiative its University of Pennsylvania partners are calling the first of its kind in the country.

Approaches to AI vary in schools across the United States. Some systems have banned it, full stop; but best practices “are where there is some overall guidance and they empower the teachers to be creative and to come up with new ideas,” said L. Michael Golden, a vice dean at Penn’s Graduate School of Education.

The district already has guidelines in place about using generative AI, but “Pioneering AI in School Systems,” scheduled to begin in March, will train district administrators, principals, and teachers in best practices and possible pitfalls in incorporating artificial learning.

» READ MORE: The School District of Philadelphia's Digital Access Hub

The aim is to roll out the program to other school systems, possibly nationwide and beyond, Penn and district officials say.

“Philadelphia will be on the leading edge,” Golden said. “We want to understand what’s possible and make sure we’re mitigating against any risks.”

How will the training program roll out?

Employees will get different types of training.

District central office administrators will work on strategic planning, governance, and policy development for AI integration. Principals will learn to implement AI tools in schools, and teachers will get hands-on training “to personalize learning, enhance instruction, and use AI-driven data to monitor student progress and provide timely support,” according to Penn officials.

What could that look like?

In the classroom, teachers might use AI to create rubrics for evaluating student work, to draft parent emails or newsletters, or for other day-to-day tasks, said Michelle Harris, an executive director of educational technology in the district. They might employ it to find “different ways to present a task that maybe students didn’t understand.”

Other possible uses include using speech recognition to support students with disabilities and creating interactive content.

Fran Newberg, the school system’s deputy chief for educational technology, described Philadelphia’s approach to AI as “conservative” but said officials were excited to safely explore how machine learning might enhance student and educator experiences.

Philadelphia’s school system has begun offering optional 90-minute AI trainings, and so far, more than 400 educators have participated. But with the Penn partnership, more comprehensive training is coming: first for central office staff, then a full two-day training with a cohort of principals. There will be paid summer intensive opportunities for teachers, and officials said they also plan to offer courses to parents and other family members via the district’s Parent University, which will be relaunching soon.

How will Philly schools use AI tools?

District leaders have issued staff plenty of cautions around AI already: Use only approved tools to ensure data privacy and network security. Know that AI makes mistakes and can be biased because it derives its information from the internet.

And “if the product is free, then you are the product,” said Andrew Speese, the district’s deputy chief information security officer. “We do take those things seriously, and research does show that whatever goes into those models can come out.”

(One approved tool for high school students is Gemini, Google’s AI product, because the district has received assurances that because it is an educational organization, the data its users input will not be used to train the AI model, and that if student information is mistakenly entered, it won’t appear elsewhere, Speese said. The school system allows students in kindergarten through 12th grade to use Adobe Firefly, a text-to-image generator.)

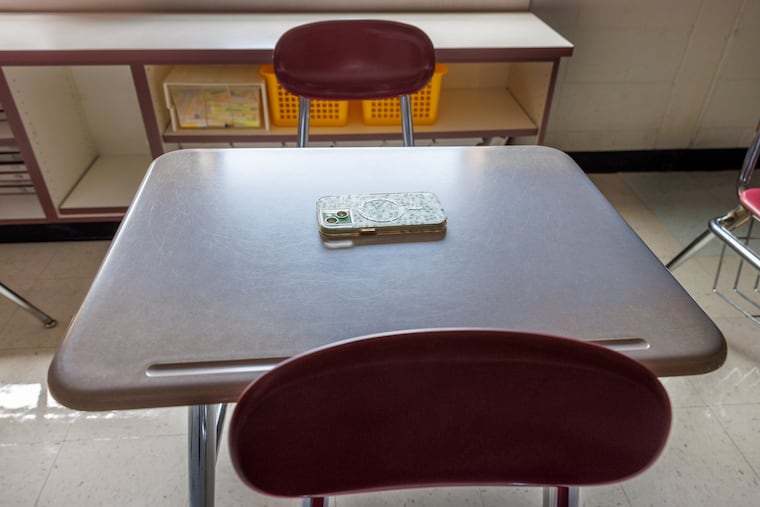

AI cannot and should not replace the interaction between student and teacher that sparks learning, or the district curriculum, system leaders said.

“AI is really something that can support you, but you still need that content knowledge, and you still need that expertise,” said Luke Bilger, who also works as executive director of educational technology. “You have to be able to read or review the material, edit it, or sometimes even say, ‘This is a hallucination. This fact isn’t even real.’ It’s very important that people know that it’s not just a prompt, copy, paste, done, but this is just really step one, and there’s more to do once you get information from AI.”

How are schools navigating the risks?

At a recent principal professional development session where AI was discussed, Newberg expected strong reactions, she said.

“I saw a little apprehension, and I saw a lot of excitement at the same time,” Newberg said. “And I think the apprehension is very healthy.”

Using machine learning in schools “can provide numerous opportunities to prepare our students to thrive in an AI-infused world,” the district’s AI guidelines read.

But, it also “carries risks related to data privacy, bias, academic integrity, cybersecurity, mis- and disinformation, and over-reliance — potentially at the expense of essential human skills. We therefore recognize that generative AI implementation must focus on legal and ethical compliance, as well as a deliberate, equity-focused adherence to our core values of safety, equity, collaboration, joy, and trust.”

Golden, from Penn GSE, said Philadelphia is on the right track — systematically exploring ways that AI can facilitate and enhance its core work.

“It’s exciting that the School District of Philadelphia wants to be innovative, but in a very measured way,” Golden said. “They’re trying to make sure that their professionals and their students are very much ready for the future.”

Arthur Steinberg, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, said the union’s members welcome technologies that help ease bureaucratic burdens.

“Teachers enter the profession with a passion for educating young people, and are too often dismayed by the volume of rote tasks and paperwork that administrators foist onto them,” Steinberg said.

But, he said, PFT was not consulted on the new program, and “any new technology that impacts our members’ ability to perform their primary function — teaching — should be introduced in cooperation with the PFT. We hope to hear directly from district administrators what their intentions and designs are for the [AI] program.”

Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr. said in a statement that the district was grateful to Penn and the Marrazzo Family Foundation, which is funding the full cost of the AI program, “for paving the way for the integration of artificial intelligence in our classrooms.” (Penn officials declined to say how much money was donated to cover the program cost; it’s being provided free to Philadelphia, and costs to future districts will be determined.)

There’s a digital divide in the city, where some students have access to resources and others don’t, Watlington said, but partnering with Penn “will help advance academic achievement for our students in STEM and technology-related fields by equipping our educators, school leaders, and district administrators with tools needed to make sure our students graduate college- or career-ready.”