As free speech issues rage on campuses, Rutgers’ president is joining the national movement to promote civil exchange

“Everybody believes in free speech until they hear something they don’t like,” said Jonathan Holloway.

Free speech on college campuses has become an increasingly hot issue: Some argue that certain controversial speakers should not be permitted, while others assert the exchange of ideas, even the most vile, shouldn’t be barred.

Wading into the mix is Jonathan Holloway, the president of Rutgers University, who has joined a national movement of more than a dozen college presidents committed to championing free expression, civic preparedness and the civil exchange of ideas on campus.

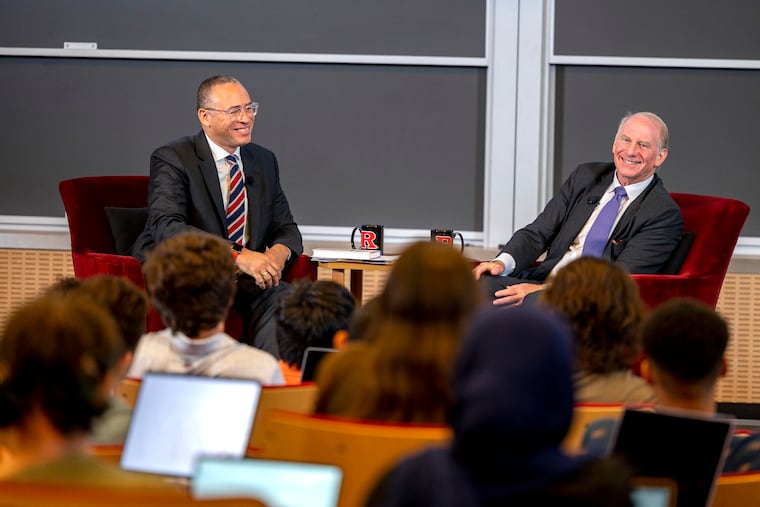

For his part, Holloway is teaching a freshman seminar “Citizenship, Institutions, and the Public,” where he invites prominent government, business, media and political figures — including those he doesn’t necessarily agree with — for debate about the state of the nation. Among those he’s had so far are the president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, a prominent Baptist pastor, a former Goldman Sachs executive and the chief Washington correspondent for Fox News.

» READ MORE: Rutgers’ president on the medical school merger, that vote of no confidence, and the faculty strike

He also made the issue a core message in his new student convocation address in August, encouraging everyone to learn to listen to one another.

“Everybody believes in free speech until they hear something they don’t like,” Holloway, 56, said during an interview this month in his New Brunswick campus office. “That’s the moment when you have to say if you really believe, then you have to deal with this ugly thing that you don’t like.”

Civil exchange is also integral to the college experience, he wrote in an essay with Roslyn Clark Artis, president of Benedict College, a historically black college in South Carolina.

“We have seen students drown out speakers with whom they disagree, faculty hold back from sharing viewpoints that might be deemed controversial, and politics influencing hiring decisions,” they wrote. “This resistance to people and positions that are different is antithetical to the exchange of ideas that should be core to the college experience.”

» READ MORE: First black president for Rutgers University expected to be appointed

The initiative is led by the Institute for Citizens and Scholars, a Princeton-based nonprofit founded in 1945 to prepare more professors to teach following the GI bill, but has now expanded to focus more broadly on civic preparation. The institute brought the group of presidents together to reprioritize the role colleges play in producing good citizens, with the free speech initiative as their first project, said Rajiv Vinnakota, the institute’s president.

The presidents’ project was born in part out of a conversation that Vinnakota and Holloway had in 2020, shortly after Holloway became president, about the need to better focus on developing good citizens — those who are well informed, productively engaged for the common good, and committed to democracy, Vinnakota said.

Vinnakota was having similar conversations with other college presidents, too, especially amid the pandemic and racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd that inflamed tensions on campuses.

Presidents, Vinnakota said, were under tremendous pressure when they tried to take on controversial issues and thought they could draw support from one another. Now the effort includes presidents from different types of institutions, among them Cornell and Duke Universities, the University of Notre Dame, the University of Pittsburgh, and Wellesley College.

“There is strength in numbers in doing this hard work,” he said.

‘Critical for university leadership to step up’

“We were just thrilled to see all these presidents stepping up to make this one of their initiatives for the year,” said Laura Beltz, director of policy reform for the Philadelphia-based Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, “even more so now, when we see all this division on campuses with regard to Israel and Hamas. It’s even more critical for university leadership to step up and tell their students that they have the right to freedom of expression no matter what their viewpoints may be.”

Other than cases where speakers are clearly inciting violence or harassing or discriminating against someone directly, speech — even hate speech — should be permitted, she said. Rutgers recently ranked 120 out of 248 universities on FIRE’s survey that gauges how students perceive campus support for free speech, she said.

» READ MORE: Critics in an uproar over speakers at this weekend’s Palestine Writes literature festival held at Penn

The University of Pennsylvania has been in the crosshairs since the Palestine Writes literature festival was held on campus last month, with some criticizing speakers who have had a history of making antisemitic remarks. Some heavyweight donors, including Marc Rowan, a Wharton graduate and CEO of Apollo Global Management, and Jon Huntsman Jr., former governor of Utah and a former U.S. ambassador, have since withdrawn financial support for Penn for not taking a strong enough stance against those speakers and for its early response to the Hamas attack.

Rowan called on Penn president Liz Magill and board chair Scott L. Bok to resign.

» READ MORE: Penn donor who gave $50 million calls for university leaders to resign over ‘embrace of antisemitism’

But other donors and supporters, including Penn’s alumni president, according to the Daily Pennsylvanian, the school newspaper, have backed Penn’s response, which was to condemn the Hamas attacks as terrorism and pledge to fight antisemitism, while supporting free exchange of ideas on campus. Former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, a Penn alumnus, told CNN this week that he didn’t think Magill’s mistake was severe enough that she should resign.

“If I had to step down as governor every time I made a mistake,” he told CNN, “I wouldn’t have made it a week.”

‘We’ve lost big donors’

Holloway said Rutgers has faced financial consequences for standing by free speech.

“We have lost millions of dollars in gifts because this particular professor tweeted something,” he said, declining to name the professor.

“We’ve lost big donors who have a history of giving seven-figure gifts. That is a really hard and painful thing because my job is to raise money for the university.”

He said if a speaker is invited to campus by a student group, faculty or department through the proper channels, that person can speak.

“We don’t disinvite speakers,” he said.

While he wasn’t familiar with the details of the Palestine Writes festival, Holloway said it sounded like the group went through proper channels, but as people learned about the speaker lineup, some felt threatened or harmed.

“That’s when things get into that really messy place,” he said.

The upheaval over the canceled appearance of the Proud Boys at Pennsylvania State University last year seems more clear-cut, he said. There were clashes between protesters and counterprotesters and “the threat of escalating violence,” according to Penn State, so he understood the decision to shut it down, he said.

Last year he found out about a speaker whose views were “utterly repugnant” who was brought to campus by a student group.

“When I was confronted with this, I said they did things properly [following the process for speakers],” he said. “I do not like these views, but everything worked.”

However, if white nationalist Richard Spencer tried to come, “that’s a trip wire for me,” he said, noting threats of violence and the $500,000 the University of Florida spent for security to host him.

‘We build trust on a one-to-one basis’

Holloway said he’s not had to prohibit a speaker, “but I think it’s inevitable.”

Then, he said, someone will ask “how come you allowed this and not this and the answer is it’s deeply subjective. That’s not going to feel satisfactory, but it’s honest.“

In his convocation address, he told students they will hear speech they find “unsettling and perhaps offensive.”

That hit home with Jack Reicheg, 18, a freshman from Princeton who is in Holloway’s class. A week later, he passed someone aggressively preaching Christianity on campus.

“It made me think that it’s not something I have to get involved with,” he said. “I can just choose to ignore it.”

Emma Perez, 18, a journalism major from Parsippany, also in Holloway’s class, said it’s frustrating when people aren’t willing to learn the pros and cons of an issue.

“Free speech is totally viable with the right education,” she said.

Discussions in one of Holloway’s recent seminar classes acknowledged the inherent difficulties when views are so opposing.

“How can I trust somebody whose worldview doesn’t have room for someone who looks like me or looks like you?” Holloway asked.

Vinnakota responded: “You engage with that person. ... In the end as human beings, we build trust on a one-to-one basis ... you get to know the person. ... You try to understand them.”