How a South Jersey school district is implementing a cell phone ban to ease classroom distractions

Superintendent Andrew Bell said the problems with cell phones had become untenable. Teachers were frustrated trying to enforce the rules in class. Cyberbullying was on the rise.

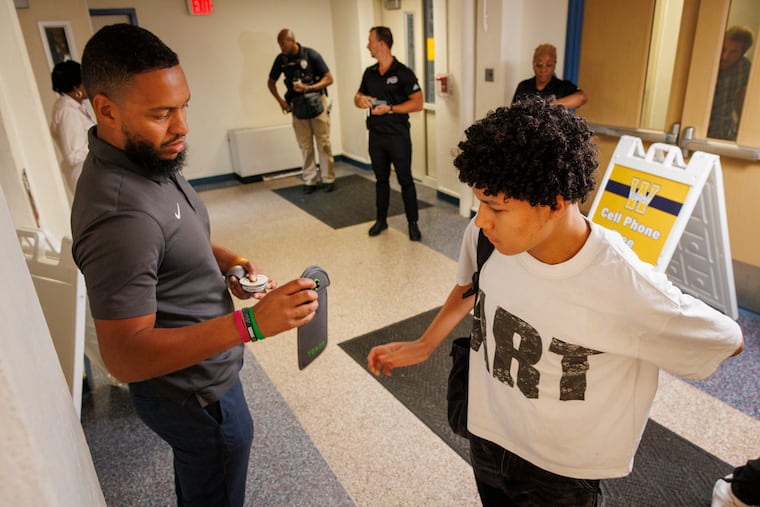

Students at Woodbury High School begin lining up shortly after they arrive at 7 a.m. for a check-in: to lock up their cell phones for the duration of the school day.

A new policy that took effect at the beginning of the school year bans students from using their cell phones and other electronic devices, including wireless headphones, during school. The devices are kept locked in a pouch until the final school bell.

The South Jersey school system joins a growing number of schools nationwide that are trying to limit cell-phone use while students are in school. Educators say the restrictions are needed to keep students engaged in learning, without distractions.

» READ MORE: Pa. is offering schools money for lockable cell phone pouches. Here’s why some Philly-area schools aren’t taking it.

Superintendent Andrew Bell pushed for a tougher approach after a policy in place for years banning students from using their cell phones proved difficult to enforce. Under that rule, students were instructed to keep their phones in their lockers or tucked away in backpacks.

Now, Bell said, “We just removed a distraction. We think it’s a game changer. Teachers are ecstatic to have control of the classrooms back, and not in a battle over cell phones.”

‘We had to do something’

Bell said the problems with cell phones had become untenable. Teachers were frustrated trying to enforce the rules in class. Cyberbullying was on the rise, with students using the devices to carry over conflicts that often began in neighborhoods, he said.

“We had to do something,” said Dwayne Dobbins, coprincipal of the high school. “Our kids weren’t paying attention.”

Senior Cassie Gallagher, 17, applauded the new policy but acknowledged it was a culture shock. Already, she can see a change in the school environment. Students are more attentive in the classroom and socialize with each other more, especially at lunchtime, she said.

“I have seen myself struggle downhill in school just because I use my phone so often in classes,” Gallagher said. “We’re surrounded by technology so much nowadays that it is really hard to get out of that.”

Bell said the district, which enrolls about 1,600 students, spent $30,000 in federal pandemic relief funds to purchase gray neoprene pouches made by Yondr, a California-based company. The students keep the locked pouches in their possession all day. School officials have portable and mounted magnetic keys that are used to unlock the devices at dismissal.

As older students arrived at Woodbury Junior-Senior High at the beginning of a recent school day, many already had their phones out ready for lockup. Some had to dig in their pockets or backpacks to pull the devices out. Signs in front of the entrances read: “Cell phone free campus 7:15 a.m. to 2:37 p.m.”

“Make sure they’re locked up,” Kyle Grizzard, the school’s dean, told them. “Everything has to be away.”

Students without their pouches must place their phones in a box and retrieve them from the office at the end of the day. Six phones were placed in the box on a recent school day. Every student was assigned a pouch, which costs $40 to replace if lost or damaged.

There is a separate entrance for sixth- through eighth-grade students who attend the junior high school in another wing. The same procedures and bell schedules are followed at both entrances, staffed by teachers and administrators.

The cell ban applies to about 750 students in sixth through 12th grades. Woodbury also has three elementary schools for pre-K through fifth graders, but few have cell phones, Bell said.

School officials say the ban is working with little pushback from students, though a few have tried to bypass the policy by having a second burner phone or purchasing magnets to unlock the pouches. Bell estimates that about 95% of the students have cell phones.

» READ MORE: To ban or not to ban the cell phone? Without them, schools see more learning, fewer fights, and calmer hallways.

During the pandemic, students became accustomed to virtual learning and spending time on their cell phones, said Jeremiah Graham, 16, a junior. He believes the new policy will help his classmates cope better.

“It’s not healthy for you because you need social skills,” Graham said.

A few parents have objected, and one started a petition to block the policy. Some parents have expressed concern about being unable to reach their children in the event of an emergency, such as a school shooting.

Jessica Lorimor, who launched the petition, said she supports having a cell phone-free campus to avoid distractions, but said she would prefer a less restrictive policy, such as letting students place the devices in a bin at the start of class and retrieving them on their way out.

“For those kids who might need access, it’s a scary thought for them to not have their phones,” said Lorimor, the mother of a sixth grader. “Instead of hiding the technology, we need to find a way to work with it.”

Read the Woodbury cell phone policy

‘I’m not as exciting as TikTok’

So far, few students have been cited for violating the policy, Bell said. The policy calls for progressive discipline, beginning with a warning call home, detention, and suspension, he said.

The policy allows exceptions for students with IEPs, or individual education plans, or a 504 Plan to use wireless communication devices as part of their curriculum.

“It’s rare that you see a phone out,” Dobbins said.

Bell said he hopes the new cell phone policy will help boost academics and close the racial achievement gap. Hispanic and Black students compose about 75% of the student population and lag behind their white counterparts.

Bell said other districts have inquired about Woodbury’s policy. Cherry Hill enacted a cell phone ban this year requiring students to secure their devices during instructional time. Students may use their cell phones and other wireless communications devices during study hall, lunch, and recess.

Dobbins and coprincipal Mylisa Himmons said they have observed changed student behavior in Woodbury High since the school took a cell phone-free stance. Students are reading more books, talking to one another more, and playing board games at lunch instead of burying their heads in the phones.

“We haven’t done this to penalize or restrict,” Himmons said. “You come here to learn. Just put your phone away.”

Freshman biology teacher Megan Lucidi said it had not been uncommon to find students watching cartoons or Netflix movies during class, or FaceTiming friends at other schools. Others would frequently ask to go to the restroom and text friends to meet them there, she said.

“I’m not as exciting as TikTok,” she said with a smile. “I couldn’t compete with them. Their phone was their primary concern.”

Lucidi, a teacher for 27 years, said she is amazed by the changes since the new policy took effect. She also limits their time allowed on Chromebooks to engage them more.

“We don’t want them to be thoughtless zombies,” she said.

When the final school bell sounded, students rushed to the exits, stopping to unlock their pouches and retrieve their phones. Some immediately began checking messages and making calls on the walk home.