How’s year-round school going in Philly? Mayor Parker gave a first look.

An extended-day, extended-year pilot, which is costing the city $24 million, is serving 2,555 students in aftercare programs across the 20 district schools -- up from 1,435 students last year

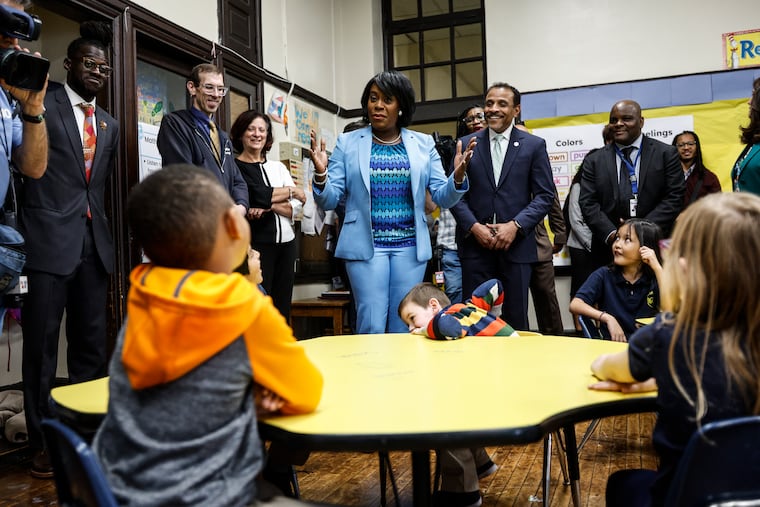

A triumphant Mayor Cherelle L. Parker on Tuesday declared the city’s implementation of a version of a year-round school program an early success, saying it expanded access to before- and aftercare for parents and would grow in years to come.

“I want you to know, I deeply understand the need to give our students access to quality experiences in quality schools,” Parker said from a podium at a Southwark Elementary classroom. “This extended-day, extended-year pilot program is a way to help close the opportunity gap.”

Twenty-five schools around the city — 20 district schools, including Southwark, and five charters — are in the initial cohort that offer before- and aftercare, as well as programming during winter break, spring break, and six weeks during the summer. Parents do not pay for the services, but spots are limited.

City officials said the extended-day, extended-year program, which is costing the city $24 million, is serving 2,555 students in aftercare programs across the 20 district schools — up from 1,435 students last year. There are 1,400 students in 14 free, district before-care programs, which the city is offering for the first time. (Six of the participating district schools start when before-care programs begin at other schools.)

There are about 113,000 children in 216 Philadelphia School District schools.

In the charter sector, which comprises 64,000 children in 87 schools, 513 students are being served in after-school programs, up from 228 last year.

Those 20 district schools are: Add B. Anderson Elementary, Carnell Elementary, Cramp Elementary, Farrell Elementary, F.S. Edmonds Elementary, Gideon Elementary, Gompers Elementary, Greenberg Elementary, G.W. Childs Elementary, Juniata Park Academy, Locke Elementary, Morton Elementary, Overbrook Educational Center, T.M. Peirce Elementary, Pennell Elementary, Solis-Cohen Elementary, Southwark Elementary, Vare-Washington Elementary, Webster Elementary, and Richard Wright Elementary.

The charters are: Belmont Charter, Northwood Charter, Pan American Charter, Mastery Pickett, and Universal Creighton Charter.

The district sees the program growing, but questions remain

Parker, Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr., and Debora Carrera, the city’s chief education officer, toured Southwark’s aftercare program Tuesday, chatting up kindergartners. They also stopped in at media lab and robotics clubs, which are not formally part of the city’s extended-day, extended-year program but are offered as extracurricular programs open to any student at Southwark.

Parker said she chose to visit Southwark because the city views it as a model, a diverse, neighborhood school that has put together a host of extracurricular experiences for students. Southwark is also part of Philadelphia’s “community schools” program, established during the Kenney administration to give certain schools a city-paid employee to help assess community needs, seek out partnerships, and provide support to remove barriers to learning.

The program has not required changes to the teachers contract this year because services are offered by community providers chosen by the city. Southwark partners with Sunrise of Philadelphia, its long-established aftercare provider, for its extended-day, extended-year program.

But in year two, the program is tentatively expected to add academic programming delivered by teachers.

Watlington said he’s in “regular communication” with both the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and the Commonwealth Association of School Administrators, the principals’ union, and has a conversation with one of the unions planned for this week.

“We’re talking about what this might look like in the future as we expand,” the superintendent said. “I can tell you, anecdotally, students and parents report that they like having these opportunities available before school and after school, we are tracking and monitoring the attendance levels, and we absolutely see our way forward in growing the numbers of the partnerships.”

Community schools are still a work in progress, and plenty of questions remain.

Not every school has a full-time coordinator on site yet, and though care is offered at each of the 25 schools, some extra enrichment opportunities have not yet been launched. Some parents say the early rollout of the program was not well communicated, and others aren’t clear on what’s different between the programs their kids attended last year and the city’s new effort.

Also up in the air is how year-round school will work for families who have children in multiple types of schools with calendars that don’t match up.

Reliable childcare that’s affordable

But Parker was in her element Tuesday, chatting up kindergartners and marveling at a drone flown in a Southwark extracurricular club.

The mayor said her grandparents, who raised her, would have loved to be able to give her activities like chess club and science activities, but they wouldn’t have been able to pay for them. And as a working parent, she appreciates the value of having reliable, quality childcare out of school time. Those were key in her mind as she envisioned year-round schooling, she said.

“The socioeconomic status that our children find as their reality on a daily basis, it should not be the sole indicator of whether or not they have access to this kind of programming,” Parker said.

And she indicated that she believed the programming fulfilled a campaign promise.

“I want to say this directly to the people of the city of Philadelphia, who for a whole lot of reasons, it appeared to me had lost some faith in government’s ability to deliver,” Parker said. “I would often say publicly, ‘I don’t want you to simply listen to what I say. I want you to watch what we do.’”