Family heirlooms retrace the history of our Black Founding Father James Forten

A weathered Bible, a table, and two samplers are a few of the artifacts that’ll be on display at Museum of the American Revolution’s “Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia” exhibit.

When Kip Jacobs, 63, was growing up in West Philly, his great-grandmother was the only family member who talked much about their ancestor James Forten, a free Black man who became a wealthy sailmaker in post-Revolutionary War Philadelphia.

“I knew that he had saved nine people from drowning in the Delaware, according to my great-grandmother, Daisy Parker,” Jacobs said. But there wasn’t much talk about abolitionism, or Forten’s old friends, like Absalom Jones, founder of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, or William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator newspaper.

Grandmother Parker, Jacobs added, “would say that he was a famous man, he was a businessman.” But that was about it. “Mind you, I just caught glimpses of this. She was 90 when I was 5 or 6.”

When Jacobs’ daughter was assigned a school report in 2007 about someone famous, he “didn’t have a whole lot of information” to share about the “famous man” in the family. They went to the library.

In “the F section,” he said, they stumbled across historian Julie Winch’s 2002 Forten biography, A Gentleman of Color, a chronicle of entrepreneurship and civic engagement that’s a milestone on the path toward a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of the birth of the nation.

Jacobs emailed Winch immediately, and they’ve been in touch ever since. The two finally met earlier this month at the behest of the Museum of the American Revolution. Both were in town to assist planning for the museum’s upcoming exhibition, “Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia,” which opens Feb. 11.

“If I learned about the connection earlier, I think it would have changed my life,” Jacobs said. “I would have taken things a lot more seriously, because I’ve had a lot of fun along the way, and it’s been a great learning experience.”

His daughter nailed her school paper for an A.

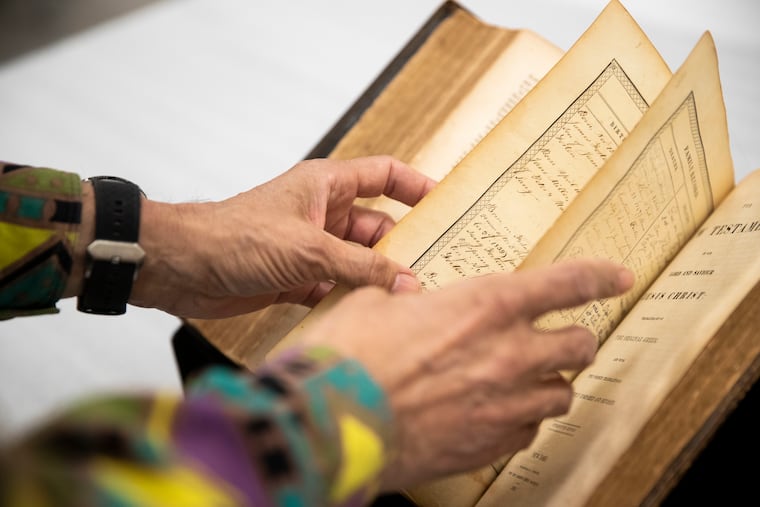

A professional photographer who lives near Chicago, Jacobs arrived in Philadelphia bearing an important artifact he is lending to the museum for the exhibition — a Bible used to record family history. Notations in its pages meticulously document everything — from the birth of James Forten Jr., Nov. 15, 1812, through James Jr.’s marriage to Jane Vogelsang in 1839, and all the way to the 1995 birth of Taylor Jacqueline Rodriguez Jacobs, daughter of James Forten’s great-great-great-great-grandson Atwood “Kip” Forten Jacobs and Marina C. Rodriguez.

Jacobs also visited Mount Zion Cemetery in Lawnside, Camden County, where 14 of his ancestors are buried. He was shown around by Dolly Marshall, a cousin and fellow Forten descendant, who is a preservationist and genealogist — the self-confessed “family detective,” who learned of her Forten family connections several years ago.

“A lot of people don’t know the Black founders,” she said, “with James Forten Sr. and his pivotal role as a Founding Father starting from Revolutionary War time. It’s very meaningful to me ... to know that there were a lot of contributions and a lot of efforts made by the African American community in Philadelphia.”

The Bible was a wedding gift to James Forten’s daughter-in-law from St. Philip’s Church in New York City, where she was baptized, Winch said.

The Rev. Peter Williams Jr. of St. Philip’s had married James Jr. and Jane Vogelsang of New York; a “happy and sad” event, Winch noted.

“It took place at the bride’s home because her mother was dying of tuberculosis. And the same day the couple was married, the bride’s mother died.”

The Forten Bible, never before seen in public, is one of several family artifacts that descendants are loaning for the exhibition.

A Philadelphia-made table that stood in the home of James and Charlotte Vandine Forten on Lombard Street between Third and Fourth Streets is being loaned by Marcus Huey, a Forten descendant living in Phoenix, and his wife, Lorri. The table has been in the family for seven generations.

The Hueys are also lending two samplers made by James Forten’s daughters Margaretta and Mary Isabella, in 1817 and 1822, a silver spoon from the 1840s engraved with the letter “P,” and a candle snuffer — both owned by Philadelphia’s Purvis family.

The Forten writing table and the two samplers, Huey wrote in an email, were passed down from James Forten to daughter Harriet, then to her son, Dr. CB Purvis, then to his daughter, Dr. Alice Hathaway Purvis, then to her son, the Rev. John Loring Robie, then to his stepdaughter, Sidney June Simpson (Huey’s mother), and finally to Huey.

.

The Forten and Purvis families are intimately intertwined. Harriet and Sarah Forten — two of James and Charlotte’s daughters (they had nine children) — married brothers Joseph and Robert Purvis, abolitionists who worked with William Lloyd Garrison and James Forten in establishing the American Anti-Slavery Society. They also worked with William Still on managing the Philadelphia hub of the Underground Railroad.

Charlotte Forten and three of her daughters — Harriet, Sarah, and Margaretta — were cofounders of the Female Anti-Slavery Society, the first integrated women’s abolitionist organization in the U.S.

It is impossible to understand the evolution of the nation or the social and political roles of Black Americans, without addressing the Forten family and their relations with families such as the Grimkés and the Purvises, argued Matthew Skic, the museum’s exhibition curator. This exhibition, is only one of a number of museum projects tied to the protean Forten family of educators, poets, photographers, writers, and activists.

James and Charlotte Forten’s granddaughter Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten Grimké, a poet and educator, was also a writer and activist.Her best-known work remains her diary, The Journal of Charlotte L. Forten, still in print.

James Forten was also good friends with his neighbor, composer Francis Johnson, who set to music his daughter Sarah Louisa Forten’s poem, The Grave of the Slave.

“It was published in [Garrison’s newspaper] The Liberator,” Winch said. “When it was set to music, it became a standard at anti-slavery rallies.”

When Winch started her research on Forten over 20 years ago, she said there was minimal information.

“I sort of dreamed about this,” she said about the exhibition, “about him getting the visibility he deserved.”

“Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia” opens at the Museum of the American Revolution on Feb. 11, 2023. For more details, visit: amrevmuseum.org/at-the-museum/exhibits.