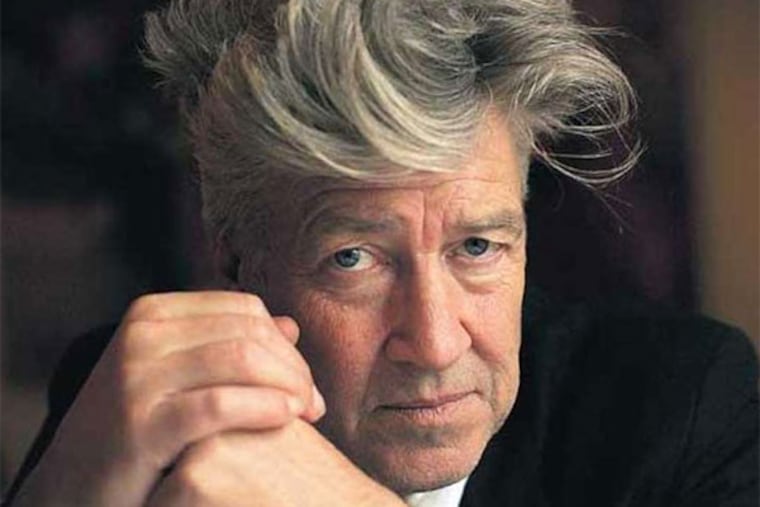

David Lynch wouldn’t be making films if it hadn’t been for Philly’s ‘filth’

PAFA alum Lynch made only three films in Philly, but the city has steeped into the filmmaker's larger distinct style.

In 1965, on the advice of his artist friend Jack Fisk, a 19-year-old painter from Montana enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His name was David Lynch.

It was at PAFA, in one of the school’s airy artist’s lofts, that the young Lynch had a revelation late one evening. Looking at a painting of a garden at night, while enjoying a smoke (naturally), Lynch heard the sound of wind and suddenly witnessed the green paint on his canvas writhing. He was struck, in that instant, by a deep need that would inform his evolution as an artist: he wanted to see his paintings move.

» READ MORE: David Lynch, visionary filmmaker behind ‘Twin Peaks’ and ‘Mulholland Drive,’ dies at 78

Lynch, the American filmmaker known for surrealist all-American nightmares like Blue Velvet, Lost Highway, and Mulholland Drive, lived in Philadelphia for just five years, splitting his time between the academy, a few shabby houses in Fairmount (back when Fairmount was still shabby), and a Germantown studio where he got a job printing engravings.

It was in Philly that he met and married his wife, Peggy Lynch (nee Reavey, a fellow artist), and where the two welcomed their daughter, Jennifer (herself a prodigious television director). In Philly, Lynch would create his first short films and start on his weird, winding path to becoming one of American cinema’s most formidable and singular talents. He has called Philadelphia “his greatest influence.”

Still, anyone at the local tourism board looking to leverage Lynch’s comments on the city for some good publicity may be hard up. In a 1987 BBC documentary, he called Philadelphia “one of the sickest, most corrupt, decadent, fear-ridden cities that exists.” In 1980, Lynch recounted a story to the New York Times about seeing a woman in Philadelphia grabbing her breasts and complaining, in a babyish voice, that her nipples hurt. As he told the reporter, in typical understatement: “This kind of thing will set you back.”

During a 2014 talk at the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, hosted in conjunction with a retrospective of Lynch’s paintings and films at PAFA, Lynch expounded on his feelings about the city. “It was a filthy city,” he said. “In the atmosphere there was fear, there was violence, there was despair, and sadness. There was a feeling of insanity. … This kind of seeped into me.”

This seeping in is clear from Lynch’s first attempt to bring his paintings to life. Produced for $200, 1967’s Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) is a looped four-minute student film, shot on a 16mm Bolex camera, depicting mutant, humanoid, Francis Bacon-esque figures retching repeatedly, their melting faces connected to stomachs that look vaguely like automobile engines.

This uncanny melding of the industrial and the organic carried over to The Alphabet (1968). Shot at the Lynch’s trinity home at 2429 Aspen St., it features Peggy Lynch in a blacked-out bedroom, spewing blood over stark white bedsheets, while reciting the alphabet song.

» READ MORE: The 50 greatest Philly films, ranked

Lynch’s third and final Philadelphia film was the markedly more ambitious The Grandmother, from 1970. Again mixing animation and live action, it’s a parable of a pale-faced young boy who, hoping to escape the wailing abuse of his parents, plants a secret seed in some soil in his bedroom, and grows a grandmother to protect him. Its depiction of American nuclear family dynamics as fundamentally hellish, and its frank psychosexual subtext, would prove enduringly Lynchian preoccupations.

While making The Grandmother, Lynch received interest (and a scholarship) from the American Film Institute and the Lynches moved from Philly to Los Angeles, where Lynch set to work on his first proper feature: Eraserhead. Starring actor Jack Nance (who would become a Lynch regular) as a fidgety cuckold charged with caring for his ex-girlfriend’s monstrously deformed baby, the film became an instant hit in the late-night, midnight movie circuit. In the movie, Henry’s girlfriend Mary gives her house number as 2416 — the same address the Lynches lived at on Poplar Street.

Though shot in California, Lynch has called Eraserhead “my Philadelphia Story.” It’s a play both on George Cukor’s 1940 romantic comedy (which presents a differently complicated view of love and marriage) and on the city itself, whose postindustrial landscape of broken down factories, and general atmosphere of evil and fear, influenced the film. The Callowhill neighborhood, not far from where Lynch lived and worked, has been termed by some locals as “Eraserhood.” Nearby, Love City Brewing even produces an Eraserhood IPA, described as “a love letter to our neighborhood.”

Philly would pop up for the occasional cameo in Lynch’s later works. Most notably, it’s where Lynch’s own character in the Twin Peaks TV series and film, FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole, is stationed. And there’s certainly a feeling of Philadelphia — that mix of decadence and decrepitude, a sense of high-minded American idealism betrayed — that haunts all his work. But it’s in those early shorts, and in Eraserhead, that the director’s complicated feelings about the city are most evident. Lynch’s feelings about Philly may be, at best, ambivalent.

And unlike most people who deride the city as a filthy, corrupt, fear-ridden hellhole, David Lynch actually lived here. He probably wouldn’t be making films had he not.