In 1957, Little Richard saw a shooting star and returned to church. In 1969, his rock and roll comeback brought him to the Atlantic City Pop Festival.

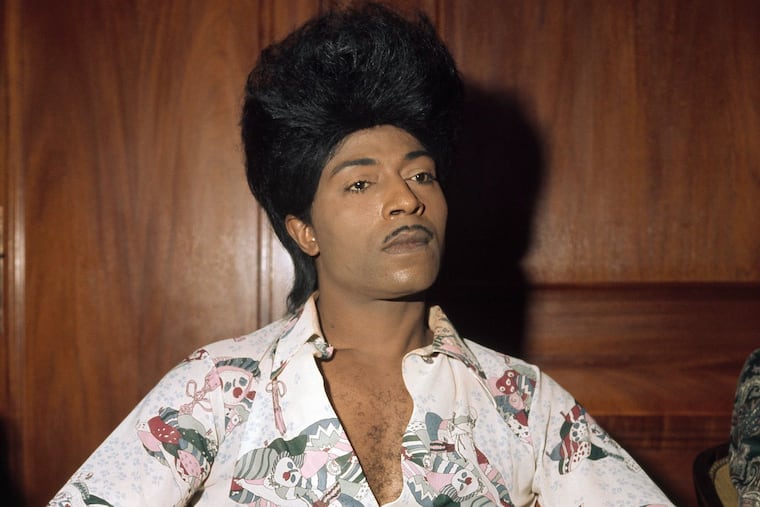

Lisa Cortés’ new documentary 'Little Richard: I Am Everything' celebrates the 'architect of rock and roll' and examines his legacy.

In the summer of 1969, Little Richard headlined at the Atlantic City Pop Festival, which featured many acts that would play Woodstock two weeks later.

In director Lisa Cortés’ documentary Little Richard: I Am Everything, the performance at the South Jersey countercultural gathering is remembered as an incandescent triumph for the electrifying “quasar of rock.”

The movie, which screens at two Philadelphia theaters Tuesday before it starts streaming April 21, depicts the life of the Macon, Ga., trailblazer born Richard Penniman as one of near constant struggle.

Although the pompadoured, piano-pounding innovator’s hits for Specialty Records in the 1950s — “Tutti Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally,” “Rip It Up” — broke through to pop audiences and brought Black and white teenagers together, Richard was always seeking recognition and remuneration he felt he had been unjustly denied.

In I Am Everything, Cortés emphasizes the conflicts within Richard as a Black, overtly queer, outrageously flamboyant performer who careened between extremes. The singer who sometimes performed in drag as Princess LaVonne when he was starting out obliterated norms, bringing sexualized, irresistibly ecstatic music to the masses and spreading a gospel of personal freedom that shaped gender fluid pop, from David Bowie to Prince and Harry Styles.

But a strict Southern religious upbringing — his church deacon, saloon-owning father called him “half a son” — convinced him that he was making the Devil’s music. He publicly renounced homosexuality and enrolled in Bible school, recording spiritual music on albums like Swingin’, Shoutin’, Really Movin’ Gospel, a 1964 collaboration with Sister Rosetta Tharpe, his fellow gospel-bred rock and roll influencer, who’s buried in Philly’s Northwood Cemetery.

When Little Richard saw a star crossing the sky in Australia in 1957, he took it as a sign that he needed to go back to the Church (it was later thought to be Sputnik), but he returned to secular music in the 1960s, in need of money. The Atlantic City gig came with Richard on the comeback trail.

“I saw all my friends on the hill, and I was still in the valley,” Richard says in one clip.

When Janis Joplin, who preceded Richard on stage, got seven standing ovations, his road manager, Keith Winslow, was worried. “Richard said, ‘Get in the limousine, go back to the hotel and get my mirror suit.’ They cut all the lights, put the spotlight on him, and he spun around like a glass ball,” Winslow recounts.

With Richard, the profane and sacred were two sides of a dualistic coin.

» READ MORE: Little Richard, electrifying rock-and-roll originator, dies at 87

“There were times when I went and slept in the bathtub because the suite was full of naked people,” Winslow says. “But he’d be sitting there with the Bible right beside him. We had prayer every day.”

I Am Everything is in love with its subject. How could it not be? But it subscribes a little too thoroughly to his self-proclaimed greatness. “I’m not conceited. I’m convinced,” was a favorite catchphrase of his.

In his 1997 speech at the American Music Awards, he proclaimed: “I am the originator, I am the emancipator, I am the architect of rock and roll! I’m the one who started it all!”

The rock and roll explosion of the 1950s grew out of a conversation among many artists. Richard didn’t do it himself, though he was arguably the most scintillating of them all.

Mick Jagger and Tom Jones are among Cortés’ fresh interview subjects, Paul McCartney and John Lennon are heard in vintage clips, and Winslow says Presley came backstage to tell Richard “you will always be the true King of Rock and Roll.”

Along with Billy Porter and Nona Hendryx, the majority of the documentary’s expert interviewees are Black historians, such as Jason King, Zandria Robinson, and Tavia N’Yongo, speaking to the whitewashing of American popular music. (Pat Boone covering “Tutti Frutti” is painful to watch.)

The heartbreaking crux of I Am Everything is captured by drummer Tony Newman, who backed Richard on a tour of England in the 1950s.

“I guess he held himself responsible for the degradation he brought to the world,” Newman says. “But what he gave us was freedom.”

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” screens at Landmark Ritz Five, 214 Walnut Street and Cinemark University City Penn 6, 4012 Walnut St. at 7 p.m. April 11. The movie will be available to stream on Amazon Prime and other VOD platforms on April 21.