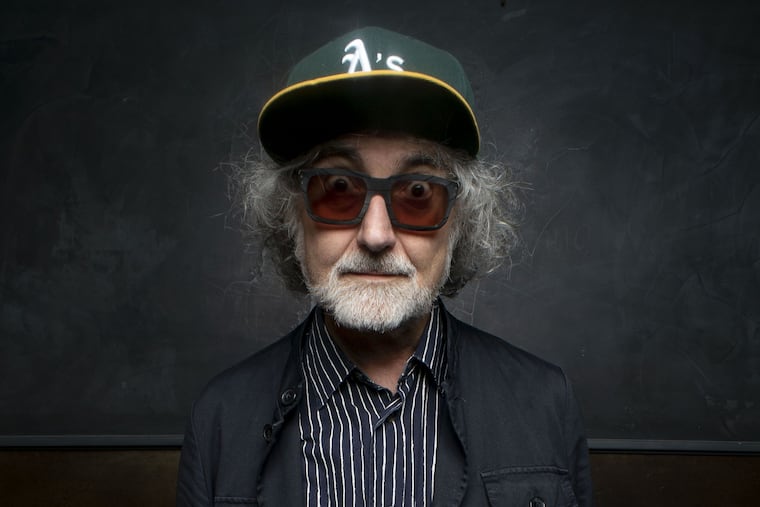

Back from the brink of death, Scott McCaughey rocks on at ‘Stroke Manor’

Scott McCaughey passed out on a street in San Francisco, far from his Oregon home, only to be diagnosed with a stroke that left him in the ICU. Now, he's back on tour.

When Scott McCaughey began work on the new Minus 5 album, the veteran songwriter and bandleader did it in his usual way, writing lyrics in his trusty song notebook that he would later set to music.

The difference this time was that McCaughey was in an intensive-care unit in a San Francisco hospital. And the words that he was jotting down didn’t make sense to him. In fact, he didn’t even know if they were words.

“It was a real mess,” says the indie rock rock lifer, who will bring a star-studded Minus 5 lineup to Johnny Brenda’s on Wednesday, June 26 in support of Stroke Manor (Yep Roc ***). “A jumble.”

“I just started to scribble things in my little notebook,” says the multi-instrumentalist singer and producer whose name is a lot easier to pronounce — it’s “McCoy” — than it looks.

Between the Minus 5 and the Young Fresh Fellows, the other band McCaughey, 64, leads, he has released 25 albums since 1984, but is probably best known for the 17 years he spent as an auxiliary member of R.E.M. He talked on the phone last week from his home in Portland, Ore.

“I just wanted to make something happen in my brain," he recalls. "When I look back at them I don’t have any idea of what I’m talking about. It’s just little glimpses of reality peaking through. Most of it is just completely out there. And that’s what turned into the record.”

In November 2017, McCaughey, was in the ICU because he had suffered a severe, life-threatening stroke. Out on a stroll during a day off with the Minus 5 — who were playing on their own and backing Texas songwriter Alejandro Escovedo — he suddenly felt dizzy, and then slumped to the ground, semi-conscious.

He was traversing the Tenderloin, home to much of San Francisco’s sizable homeless population. “I was in an area where it wasn’t unusual for people to be stepping over a body on the sidewalk,” he says.

Two people who thought McCaughey had a seizure eventually called an ambulance. The emergency room doctor, though, assumed that McCaughey, who by then was unconscious, was a drug casualty and waited 24 hours to give him an MRI.

And even then it was only at the insistence of McCaughey’s friend and bandmate Peter Buck, who was onstage when fellow R.E.M. drummer Bill Berry had a brain aneurysm in 1995 (he survived) and was with Col. Bruce Hampton in 2017 when the musician died of a heart attack at his own 70th birthday party.

When the results of the magnetic resonance imaging test — immortalized in song on the surprisingly jaunty “MRI” on Stroke Manor — were in, Buck, Minus 5 drummer Linda Pitmon, and McCaughey’s wife, Mary Winzig, were told that McCaughey had a stroke and that he would never play music again.

That news was met with grave concern in the music community because McCaughey is an enormously capable and well-liked collaborator who has contributed to dozens of projects.

Among them: He’s a member of Filthy Friends (essentially the Minus 5 plus Sleater-Kinney’s Corin Tucker), the Baseball Project (with Buck, Pitmon and her husband, Dream Syndicate leader Steve Wynn), and various other endeavors with Buck, including Arthur Buck, Tuatara and the Venus Three.

Wesley Stace, the Philadelphia-based English songwriter and novelist, has known McCaughey since the early 1990s and worked with him many times, including on his 2009 album Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, with the Minus 5 as backing band.

Stace calls McCaughey “a fantastic catalyst. He’s super friendly and massively enthusiastic about seemingly every type of music.

“He’s the fun guy who’s serious about music. People love to be around him because he brings out the best in them. He’s given his life to his love and creation of music. He’s a beautiful man. That’s why so many of us were so particularly moved and horrified by him having a stroke. And so invested in his getting better.”

McCaughey had renewed his Affordable Care Act insurance just a week before he had the stroke, and was aided in paying additional medical expenses by fans and fellow musicians rallying around him. When he was well enough to communicate, he told his wife he didn’t want a Go Fund Me campaign or any benefit concerts. She said, “Too late.”

Music played a role in McCaughey’s recovery. “The Beatles are all and everything to me.” He cites John Lennon’s “gobbledygook” writing in his 1964 book In His Own Write, as helping to convince him that you could make a song out of lyrics like “Green turn up yellow rib, blue attack unsoftly / Purple oozing white arm eggs, running pepper salt.” (It also fits into a gibberish pop tradition stretching from “Louie Louie” to mumble rap.)

When McCaughey was still in the middle of his three-week hospital stay, Buck brought in a mini-sound system and an iPod, and put the Beatles catalog on shuffle.

“It was weird. I didn’t know the songs at first. I used to know all the songs inside out. They were familiar to me, but I was hearing them differently. I couldn’t sing along with them the way I normally would have, but it really helped just to give me a sense of comfort and got me thinking about music again.”

When he had recovered enough to record, McCaughey started Stroke Manor with the strummy, hauntingly pretty “Plascent Folk,” a song with a title whose first word “is not a word,” he says with a laugh. “I didn’t know that when it came out. I didn’t know what it meant. I though it was a word and it’s not. I guess it is now.”

Stroke Manor’s songs may not make literal sense, but it’s easy enough to suss out who “Beatles Forever (Little Red)” or “Bleach Boys and Beach Girls,” which declares that “the world is just one big towel,” are celebrating.

“When I started working with these words, the music came out really quickly, and melodically it was really strong. I hadn’t really thought of this before, but maybe the lack of literal meaning made them shift to the melodies being stronger. I don’t really know.”

The album includes one straightforward serious-minded song in the closing “Top Venom,” whose lyrics are taken from a pain index card designed for patients who can’t speak who have to point to phrases to communicate. “I am short of breath … I am in pain … I want to be comforted … I wanted to go home,” it not-so-cheerily goes along.

McCaughey has written hundreds of songs, and many of them, he jokes, have been “about being dead.”

In 2014, he released a five-LP set called Scott the Hoople in the Dungeon of Horror that kicked off with a screeching tune called “My Generation,” about rockers “born in the ’50s, children of the ‘60s ... not ready to die, die, die / Not ready to fold.” He sings that every night, along with a more macabre song called “In the Ground.” “They take on new meaning when I sing it now, for sure,” he says.

Unlike such stroke victims as South Philly jazz guitarist Pat Martino and the Kinks’ Dave Davies who had to start over from scratch, McCaughey didn’t lose the ability to play.

He’s toured with the Baseball Project as well as Filthy Friends since his stroke, but he hasn’t had to sing lead on the road yet, which he expects to be a challenge.

“I can’t really spit out lyrics the way I used to,” he says. “People say they can’t really notice it that much, which seems crazy to me, because I’m just out there concentrating with every ounce of my being.”

He expects that fronting the band will be a challenge, but is excited to take the Minus 5 show on the road. For this tour, the band will include not only Buck and Pitmon, but also Mike Mills of R.E.M. and guitarist Kurt Bloch of the Fastbacks.

“I just love music, and I love other people who love music,” he says. “And I just feel lucky every day that I get to do this. I’ve always been lucky, and I’m still lucky.

"I don’t know how it happened. When I was a kid listening to the Beatles I never thought that I would do that for my whole life. It’s kind of an accident. Because I never really drove myself to do it. I just accepted the gifts that came my way.”