The afterlife of Prince, in words and music

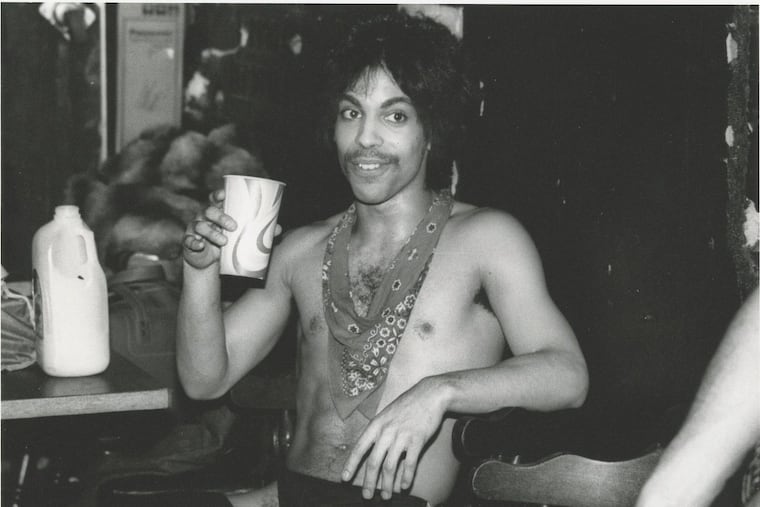

Three and a half years after his death at age 57, Prince is once again alive in pop culture, with a newly released memoir and no shortage of re-issues. But would he have wanted it that way?

In The Beautiful Ones, Prince’s new posthumous memoir-slash-scrapbook, the purple polymath explained to coauthor Dan Piepenbring that he’s not an “egotistical maniac.”

That notion, Prince suggested, stemmed from his reputation as control freak — someone who, as Piepenbring writes in his introduction, “got off on withholding the pleasures of his catalog from the undeserving masses.”

Nothing could be further from the truth, Prince asserted. To make his point, he cited “Extraloveable,” originally recorded in 1982 and considered for the Prince-assembled vocal trio Vanity 6, one of the many protégé acts, including The Time, that he routinely serviced with songs from his overabundant supply.

“Extraloveable” didn’t make the Vanity 6 album, but it became widely known to Princeophiles through bootlegs. Eventually, the horn-happy funk jam was officially released as a Prince song, first as a single in 2011, with the title altered to “Xtraloveable,” and later on HitnRun Phase Two, his last album before his death at age 57 in 2016.

He didn’t put the song out earlier because he deemed it unworthy. “It wasn’t released in the eighties because it wasn’t done,” Prince explained to Piepenbring in The Beautiful Ones (Spiegel & Grau, $30), in the latter’s dramatic recounting of his job interview/first meeting with the artist formerly known as a glyph. “If any track is unreleased, it’s because it’s not done.”

Prince reflexively exercised his prerogative to hold tight to a creation until it was good and ready to go into the world. As a result, the preternaturally talented, polymorphously perverse imp left behind thousands of hours of music, squirreled away in Paisley Park, his creative headquarters in Chanhassen, Minn.

That’s why Prince’s musical life after death is so singular. When a great, long-lived artist dies in our digital age, the immediate mourning period is marked by an explosion of content, dug up and shared on social media until we can’t help but remember what we’ve lost. That happened with Prince when he died in April 2016, just as it had with David Bowie in January of that year, and as it would with Tom Petty the next year.

But the curatorial afterlife that follows is usually about combing through archives to see if any choice cuts are left. Petty’s death spurred the release of 2018‘s An American Treasure, a worthy box set of mostly alternate takes and live versions of songs we already knew.

Sometimes an artist’s work can benefit from being contextualized, as with the stunning new The Bakersfield Sound, a 10-CD box on the Bear Family label. It casts Merle Haggard — another casualty of 2016, a big bummer of a year — in a new light by considering him alongside such California country music contemporaries as Buck Owens, Bill Woods, and Billy Mize.

But Prince was not only massively productive, he was also highly selective — and a hoarder. However, he lost the right to decide which of his music was fit for ears other than his own when he died without a will.

Three and a half years later, the vault doors have swung wide open. Not only is Paisley Park now a museum, but a campaign is underway to make available the music and materials kept from the public during his lifetime.

Last year saw the release of a thrilling solo collection with a self-explanatory title: Piano & A Microphone. Last month, the demo recording was issued of “I Feel For You,” a song recorded in 1978 that became a career-reviving hit for Chaka Khan in 1984.

That song is not among the 15 on Originals, a set that came out in June of Prince versions of songs that became better known under other artists, such as The Time’s “Jungle Love,” Sheila E.’s “The Glamorous Life,” and Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U.”

On Nov. 29, a big one is coming: a five-volume reissue of the 1982 album 1999, Prince’s second-greatest double LP. (The even more masterful Sign O’ The Times, from 1987, takes top prize.)

The project has been released with enticing singles like the itchy “Don’t Let Him Fool Ya.” And there’s plenty of worthy stuff among the 35 unreleased tracks, including “Vagina,” a riff rocker that neatly expresses Prince’s familiar fantasy of merging two sexes: “Half boy, half girl / The best of both worlds.”

In The Beautiful Ones, Piepenbring recounts combing through 5,200 personal items — photo books, scribbled notes, quasi-diary entries — seeking anything that “shed a new light on his family and his art; that demonstrated his creative process; and, as he desired, would make his readers want to create, too.”

Though Prince had cooperated fully with Piepenbring, then a 29-year-old Paris Review editor whom he chose as his trusted collaborator, he died just as the project got underway.

Prince did write a tender opening section of the book — in elegant longhand, as you would expect. It begins: “My mother’s eyes. That’s the first thing I can remember. U know how U can tell someone is smiling just by looking into their eyes? That was my mother’s eyes.”

The section on “how Prince became Prince” in The Beautiful Ones — to be celebrated at Monday in New York with a Town Hall event featuring Piepenbring, Spike Lee, Prince’s band the New Power Generation, and others — is invaluable, but also inevitably frustrating and incomplete.

Prince had told Piepenbring that the book would have “some bombshells.” They were never dropped, but it does capture a real sense of the sui generis genius from childhood tales of playing his father’s piano and the discipline and competitiveness he brought to his work.

He disliked the word “magic.” “That’s Michael’s word,” meaning Jackson. “Funk is the opposite of magic,” he explained. “Funk is about rules.” His mischievous sense of humor is also on display. Of the Ohio Players song “Skin Tight,” he wrote, "the bass and drums on this record would make Stephen Hawking dance. No disrespect — it’s just that funky.”

How would Prince feel about all this activity?

Having his closely guarded musical creations out in the world would likely have driven him mad. In 2016, his music was almost entirely absent from music streaming services. Now, there’s much more Prince than ever before.

A bad thing? Hardly. It’s unclear who’s profiting from Prince’s legacy, though somebody is, and fairness is an issue.

But it’s also true that the demand for Prince product, held back for decades, could not be contained. The pace of reissues is a little swift — last year brought an enormous Purple Rain reissue — but the projects that have come out so far in conjunction with the Sony’s Legacy label have been handled with care.

He’s too beloved. This month, when Bob Seger played the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, he paid tribute to a number of recently deceased artists. Prince got the biggest crowd reaction by far because his death still registers as illogical, if not shocking.

In life, he seemed impervious to the ravages of time, though that was partly an illusion, aided by an apparent addiction to painkillers — as well as what Piepenbring describes as the “superabundance of cosmetics” found in Paisley Park that kept him photo-op ready.

When pop cultural heroes whose art speaks to our very souls leave us, we strive to keep them in our lives any way we can. Prince valued mystery in his art and image. Now that he’s gone, that only makes fans want him that much more.