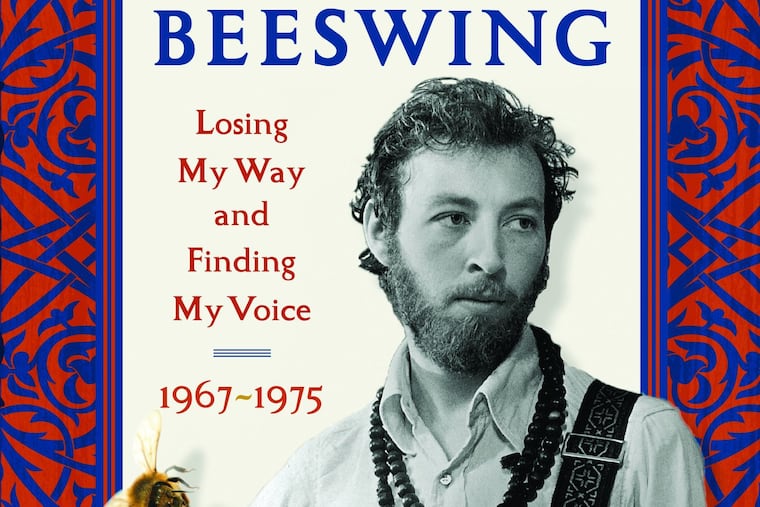

Guitar great Richard Thompson talks Fairport Convention and his folk-rock beginnings with ‘Beeswing’ memoir

The great British guitarist Richard Thompson's memoir chronicles his years with Fairport Convention and wife Linda in the 1960s and 1970s. He's doing a virtual event at the Free Library.

Richard Thompson’s combination of skills as a songwriter and guitarist is unmatched.

The musician’s career — from his rise with British folk-rock inventors Fairport Convention to his 1970s partnership with his wife Linda Thompson to three decades as a solo artist — stretches over 50 years.

But Thompson’s new memoir zeroes in on only the first eight. It’s called Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967-1975, taking its title from one of Thompson’s most beautiful songs, the gossamer “Beeswing,” which is on his 1994 solo album Mirror Blue but evokes the earlier era.

The book, which was written with Scott Timberg, will be part of the discussion when Thompson is interviewed by musician and novelist Wesley Stace in a virtual Free Library of Philadelphia event 7:30 p.m. Thursday.

Thompson is not inclined to look back longingly on his storied past. “The remotest room of my mind has been shut up for years, the windows shuttered, the furniture covered with dust sheets,” he writes as Beeswing begins. “If something is uncomfortable, I shove it in here and forget about it. When was the last time I dared look?”

“I think we all lock away stuff we don’t want to deal with,” Thompson says. But he began to excavate his memory at the urging of Timberg, a journalist and friend who died in 2019.

“He bugged me about it for a couple of years,” says Thompson, speaking from his home in Montclair, N.J. In his new home state, he jokes, “if Bruce [Springsteen] is the King, and Bon Jovi is the Crown Prince. What does that make me? The Road Sweeper of New Jersey.”

He moved east from Los Angeles three years ago to be with his partner, singer and writer Zara Phillips, who can be heard on his lockdown EP, Bloody Noses.

Of Beeswing, “Scott said, ‘This is a book you should write about the ’60s and ’70s, you were there, you could tell it like it was.’ ” Thompson was skeptical, having never written any prose longer than a short story, but “he convinced me, and I enjoyed the process. It’s a new world for me.”

Beeswing is lively, compact, and frequently funny at under 300 pages, including an appendix that describes Thompson’s dreams, including ones abut Jesus, Keith Richards, and Joni Mitchell.

The latter two are among the luminaries the young guitarist encounters, along with John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Linda Ronstadt, Phil Ochs, Glenn Frey, and Buck Owens & the Buckaroos, along with Fairport bandmates Simon Nicol, Iain Matthews and Sandy Denny.

A tight focus, Thompson hopes, will keep his readers from nodding off.

“I read Keith Richards’ biography, I read Pete Townshend’s, one on Paul McCartney — and I got bored about two-thirds of the way through,” he says. “The most interesting stuff is the first time you’re experiencing something. Unless there’s a murder in the audience, you’re not going to have anything fresh.”

The Kinks down the street

Thompson, whose 72nd birthday was Saturday, grew up in London’s northern suburbs. “The Kinks lived just down the street.” He heard guitarists Django Reinhardt, Lonnie Johnson, and Les Paul in the record collection of his father, a Scotland Yard detective. His sister, Perri, five years older, turned him on to rock and roll. She later owned a London boutique where Jimi Hendrix shopped.

“It was an extraordinary time in music, and we were right there,” he says, speaking of the Swinging ’60s milieu where Fairport came of age. “London really was the center of fashion and youth culture and music at that point.”

He writes of Hendrix’s impact. “British blues players ... learned their skills by copying records by Chicago bluesmen.” But with Hendrix in London, “the stars of the British blues scene suddenly seemed outgunned — where did Jimi’s arrival leave Eric, Jeff, Peter and Pete?” he writes of Clapton, Beck, Green, and Townshend.

Seeing Hendrix perform “left me feeling as inadequate as anybody,” Thompson writes. “But I thought that if I could not compete, perhaps I could jump sideways -- above everything else, I was striving for originality.”

That, too, was Fairport’s approach. “We took a decision to not be like all of the other bands, to have a style that was more representative of where we came from,” he says. “We had to stop being so influenced by American roots music, because we were never going to do it as well as The Band, let alone play the blues as well as Muddy Waters or country music as well as Merle Haggard.

“I think Fairport were a very important band. ... It started a whole movement in the U.K., but in other countries as well, where bands thought, if we’re going to play rock and roll, we need to do it without our own local flavor.”

“Why them, not me?”

In May 1969, Thompson was in the center front seat of the Fairport van when it crashed on the way back to London. Fashion designer Jeannie Franklyn, whom he had been dating for two weeks, was to his right. She and the band’s drummer, Martin Lamble, were killed. Thompson’s ribs were broken, but he and others in the van escaped serious injury.

Before Beeswing, he had never publicly spoken about the tragedy, though he has addressed it in songs like “Never Again,” which was written in 1969 but not recorded until Hokey Pokey, his 1975 album with his then wife, Linda. “With songwriting, it’s always been a process of trying to figure out who I am, and why I am the way I am,” he says. “But I realized there were things that I really hadn’t dealt with for a very long time.”

Does he have survivor’s guilt? He stammers for a few seconds, then says, “Yeah, I do. I was looking for another way of saying it, but I actually do have survivor’s guilt. I do think, ‘Why them, not me?’ ”

Later, that year, Fairport fired Denny after she didn’t show up to catch a flight for a tour of Denmark.

“It seems crazy looking back,” Thompson admits, “We were all still shell-shocked from the accident. If our heads had been screwed on right we would have made different decisions.”

Beeswing includes tales of a 1970 American tour that included a jam session with Led Zeppelin in Los Angeles. (The tapes have gone missing). And Fairport “finally found our target American audience” at the Philadelphia Folk Festival that year. “It seemed like the entire crowd of ten thousand was dancing. It was an amazing sight,” he recalls. (Bootleg recordings are available.)

Over the years Thompson became a formidable, underrated vocalist. But he’s been especially fortunate to write for brilliant singers Denny, who died in 1978, and Linda Thompson, with whom he made seven albums, including the 1982 classic Shoot Out the Lights, which seemed to predict the dissolution of their marriage that year. (Thompson calls it “the breakup album that wasn’t, until it turned out to be.”) Last year, their complete works were released in a box set called Hard Luck Stories.

Picking favorites

I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight, from 1974, is Thompson’s favorite of their albums together, 1969′s Unhalfbricking his Fairport of choice, and 1999′s Mock Tudor the best solo collection in his estimation. He cites Nick Drake’s 1969 Five Leaves Left as an album he’s proud to have played on: “That’s a great record.”

Thompson is effusive about both Denny and his ex-wife. “Sandy could sing in a whisper or at tremendous volume, and everything in between,” he says. “She was like Sinatra in that she owned songs. When she sang a song, it was her version you remembered. ... Whereas Linda is a more straightforward singer and more emotionally pure. And her interpretations can be absolutely devastating in a whole different way.”

Thompson finished Beeswing before the pandemic. Since then — as his 1991 song “Keep Your Distance” took on fresh resonance — he’s been cooped up in Montclair, unable to do what he’s done his entire life.

“It’s been strange,” he says. “It’s been tough, really, not having an income.”

He has been productive, with another solo EP coming in May, and a new band album written though not yet recorded. But like musicians everywhere, he’s restless for a return to normalcy, and is looking forward to outdoor dates this summer and hopes to play theaters in the fall.

“It’s been a great time for writing. But having been on the road since I was a teenager, being forced to be home has been difficult,” he says. “I’ve had enough now.”

Richard Thompson will discuss Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967-1975 with musician and novelist Wesley Stace in a virtual Free Library of Philadelphia event at 7:30 p.m. April 8. $33, with a signed book included with ticket. freelibrary.org/