Unpredictable and brilliant, Todd Rundgren wrote the playbook for how not to get into the Hall of Fame.

The dazzlingly talented Philadelphia musician is set to be inducted in the Rock Hall's 2021 class. But it's not because he wanted it more.

Back in 2014, when Hall & Oates was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, I asked Daryl Hall who first came to mind when he thought of other deserving Philly acts whose achievements had long been ignored.

Hall mentioned Chubby Checker and Teddy Pendergrass, the transcendent front man for Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, before another obvious answer dawned on him.

“Todd!” he exclaimed. “Todd Rundgren should be in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.”

Seven years later, it’s finally come to pass.

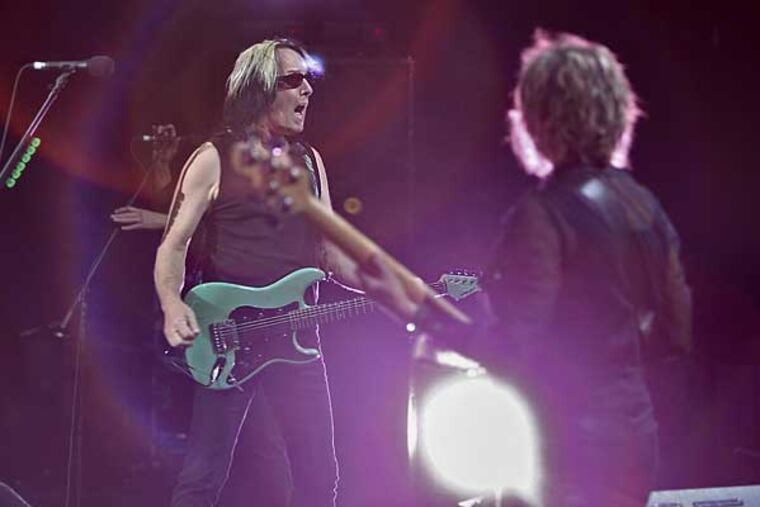

On Wednesday, the Rock Hall announced the induction of the Upper Darby native who got his 1960s start on the Philadelphia music scene with Woody’s Truck Stop and Nazz before going on to a long, unpredictable, and frequently brilliant career as an innovative solo artist.

In the 2021 Hall of Fame class, he’s going in alongside Tina Turner, Carole King, Jay-Z, the Go-Go’s, and the Foo Fighters. The induction ceremony will be held in Cleveland on Oct. 30.

In one sense, Rundgren’s eventual Rock Hall induction has felt inevitable. He’s too talented and has accomplished too much to keep him out forever. But in another, Rundgren has carried on a restless and unfocused creative life that’s antithetical to the steady, career-building model of more predictable bands like the Foo Fighters, who — unsurprisingly — are being inducted in their first year of eligibility.

By contrast, Rundgren has been eligible since 1996. He wasn’t nominated until 2019, and then again last year.

That’s despite scoring 1970s and 1980s hits like “Can We Still Be Friends” and “Bang The Drum All Day,” while also building a resume as a producer of artists as varied as Patti Smith, XTC, and Meat Loaf — whose fantastically bombastic Bat Out Of Hell is one of the biggest selling albums of all time.

Rock Hall president Greg Harris, who grew up in Bucks County and cofounded the Philadelphia Record Exchange in 1985, is thrilled to have Rundgren join Philly-born or connected inductees who include Nina Simone, Solomon Burke, Billie Holiday, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Bill Haley & His Comets, and Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff.

“Todd Rundgren is a rock and roll Renaissance man,” Harris said via email. “Songwriter, musician, performer, producer, arranger, he has done it all, and done it all very well … To celebrate, let’s synch up every speaker in Philadelphia to simultaneously play ‘I Saw The Light’ so that it echoes throughout the city, like church bells!”

When news broke on Wednesday of the Rock Hall induction, Rundgren wasn’t as celebratory: He would only admit being pleased for his supporters. He posted two terse sentences: “I’m happy for the fans. They’ve waited a long time for this.”

His signature style: unclassified

Then again, Rundgren has never pursued accolades. Throughout his career, the 72-year-old singer has followed his own creative instincts, wherever they might lead.

Among major figures in rock history, few have made a mark so indelible without being rooted in one signature style, or by so equally balancing performing and behind-the-scenes achievements. Which is one likely reason why the Rock Hall took so long to recognize him.

He made blues-rock with Woody’s Truck Stop, power-pop with Nazz, prog-rock with his 1970s band Utopia and has been a restless experimenter, both in electronic music and interactive technology.

Even his hits are widely divergent, from Nazz’s ebullient “Open My Eyes” to the beautifully disconsolate “Hello It’s Me” and downright goofy “Bang the Drum All Day.”

Rundgren’s musicianship and skill as a craftsman have always been apparent. Eric Bazilian of the Hooters definitely noticed.

“My first exposure to Todd was at an “Old Year’s Party” at the Unitarian Church in West Mount Airy when he was in Woody’s Truck Stop,” Bazilian recalled, emailing from Sweden. “It was the first time I’d ever seen anyone shredding blues guitar on a Les Paul.”

“Everything Todd has done is quality,” Bazilian said. “But, for me, his musical pinnacle is The Hermit of Mink Hollow [1978]. Every track tells a story, and all the stories interweave.”

Out go all the rules

On his 1972 album Something/Anything? Rundgren sang, produced, and played all the instruments. It was a critical and commercial tour de force. Then he followed it with what he has called an “act of tyranny” — 1973′s hallucinogenic A Wizard, A True Star.

“I threw out all the rules of record making. I would try to imprint the chaos in my head onto a record without trying to clean it up for anyone else’s benefit,” he said in a commencement address at the Berklee College of Music in 2017.

“The result was a complete loss of about half my audience at that point … This became the model for my life after that.”

In the 1970s, Rundgren was particularly prolific, releasing 13 studio albums, including those with Utopia, while also compiling a staggering list of credits as a producer and engineer, working mainly out of Bearsville Studios in upstate New York.

His projects included the self-titled album by Philadelphia’s The American Dream, The Band’s Stage Fright, Mother’s Pride by pioneering all-female group Fanny, Grand Funk Railroad’s We’re An American Band, New York Dolls’ self-titled proto-punk masterpiece, Hall & Oates’ War Babies, Bat Out Of Hell, and Patti Smith Group’s Wave.

“Todd’s an old friend of mine, and also he’s a great musician and I knew he would contribute to the musical sense of the record,” Smith told Uncut in 2004. “I think the sound of that record is beautiful.” (Smith, by the way, would be an excellent choice to induct Rundgren in October.)

He’s often been ahead of his time: In the 1990s, he performed under the name TR-i — Todd Rundgren interactive — and his pre-Napster system PatroNet was designed to eliminate the need for record labels and deliver music directly to fans.

Kevin Parker of Australian band Tame Impala, who will headline this year’s Firefly Festival in Delaware, spoke last year about the psych-pop elder statesman’s production and songwriting trademarks, such as “the phaser on the drums, his use of major 7th chords.”

The Toddhead was also rhapsodic about 1973′s A Wizard, A True Star. “We put it on our record player and it just blew all our minds,” Parker told Music Connection last year. “Like after track one we were all standing in the room like ‘what … just happened?’ It became this sort of Holy Grail for us for years.”

21st century Todd

In 2012, Rundgren remixed Tame Impala’s “Elephant,” and he has frequently collaborated with others in recent years. In 2015 he teamed with Japanese electronic band Yellow Magic Orchestra on “Technopolis.” He called out conspiracy theorists with Donald Fagen on “Tin Foil Hat” in 2017.

Rundgren released the most perverse holiday song of 2020 with “Flappie,” a translation of a 1978 Dutch song about a boy whose father cooks his pet rabbit for Christmas dinner. His forthcoming album Space Force features “Down With the Ship,” a ska goof with Rivers Cuomo of Weezer and “Espionage,” with Iraqi-Canadian rapper Narcy.

In 2019, Rundgren, who lives in Hawaii, came home to induct the Hooters into the Philadelphia Music Alliance Walk of Fame, where his own plaque is embedded in the South Broad Street sidewalk.

He spoke of being shaped by the sounds of Philadelphia, and the musical education he got from the Black music he heard on the radio. “The world knows that I’m a product of the Philadelphia music scene,” he said. “People ask me what is so unique about that, and if I have to get myself down to one thing, it’s that I grew up listening to the Geator.”

DJ Jerry Blavat, he said, “played the music that would have been called race records below the Mason Dixon line.”

During the pandemic, Rundgren stayed active in a typically tech-savvy fashion. On his Clearly Human “tour,” he was backed by a 10-piece-band in Chicago playing his 1989 Nearly Human album in virtual shows made available only to specifically targeted cities via geofencing. (There was not a targeted Philadelphia show.)

Before the Clearly Human Cleveland date in February, Rundgren explained that he has little interest in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, or any institution that wishes to enshrine his body of work while he’s still busy creating it.

“True Halls of Fame, to me, are for retirees and dead people, because your legacy has been established,” he said. “I’m too busy working to worry about my legacy.”