The history of South Asian American immigration wouldn’t be the same without the ports of Philadelphia

The city was one of the main ports where Bengali Muslim 'laskars' would jump ship and then go on to work in steel mills in Bethlehem or Chester.

“[Philadelphia] … is known as the cradle of American liberty,” wrote George Franklin in 1920. “So it was quite in keeping with the tradition of this city to have given a stirring welcome to the Indian revolutionists who paraded the streets on Sunday, Sept. 5, with their Republican flags and banners of red, gold and green.”

This passage appeared in Franklin’s essay, “Philadelphia Rings the Liberty Bell of India” in the Independent Hindustan: A Monthly Review of Political, Economic, Social and Intellectual Independence of India.

The Liberty Bell, where the freedom fighters congregated, is the first stop on the Revolution Remix walking tour by the Philly-based South Asian American Digital Archive. As the tour progresses, participants hear the stories of Amar Gopal Bose, the South Asian Philadelphian entrepreneur who started the Bose Corporation (of sound system fame), and Anandibai Joshee, the first South Asian woman to become a doctor and who studied at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

These stories, among others, are part of SAADA’s mission to shed light on the underwritten histories of South Asian immigration in the U.S., specifically in Philly.

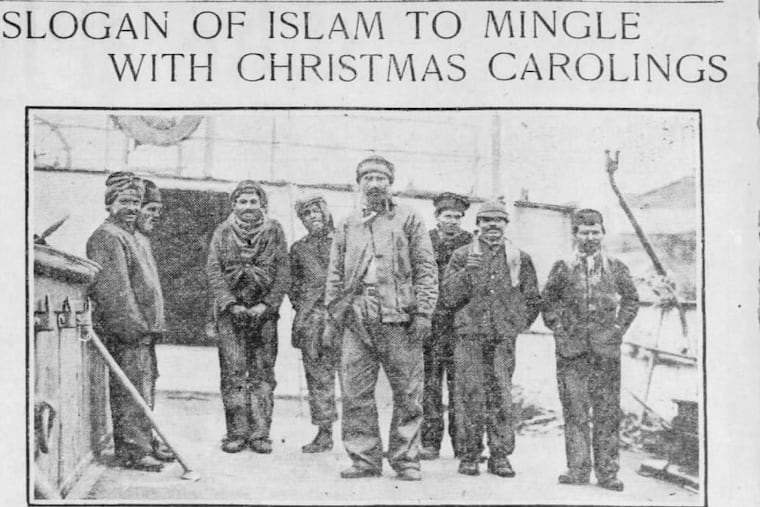

When the walk gets to the Race Street Pier, the guide pulls out an article from The Inquirer, dated Dec. 25, 1903. The headline reads: “While Christians sing ‘Peace on Earth,‘ Lascars on Tanker at Point Breeze Will Cry ‘Allah Il Allah,’ Because the Day Is Their Sabbath.”

“That year,” SAADA executive director Samip Mallick said to The Inquirer, “Eid and Christmas happened to correspond … And so the story talks about the shift workers on the ‘dark side’ of Philadelphia cooking a special meal for Eid.”

“While Christians in this Christian city are dining … the Mohammedans will partake of their staple food, rice and currie ,” the article reads before explaining the cooking procedure. “The result is said to be a most savory mess that is a favorite of not only the dusky seamen, but of their fellow tars of other nationalities.”

The Inquirer’s mention of South Asian seamen called “laskars” or “lascars” (mainly from the present-day territories of India and Bangladesh) working on British and European ships goes back to the mid- to late-1800s. There was an uptick around the 1910s when the British started using steam ships “and used their colonial laborers to do the really awful industrial work in the belly of the steam ships,” said historian and filmmaker Vivek Bald, whose book Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America formed the historical basis for the new documentary In Search of Bengali Harlem, which he codirected with the film’s protagonist Alaudin Ullah.

“It was really grueling work … And these men were essentially finding ways to jump ship in the United States … there was a demand for their labor because of [World War I],” said Bald, an associate professor at MIT. “The men started to build these clandestine networks in the 1910s to help other ship workers to jump ship and to find work on shore.”

“I call it kind of like an underground railroad,” said actor and comedian Ullah, whose father, one of these seamen, moved to New York City’s Harlem in the 1920s, where a large community of Bengali men settled after marrying African American and Puerto Rican women.

His father’s story forms the spine of the documentary that premiered on PBS’ America Reframed last night. “They felt Harlem was a place of refuge. Yes, it’s got a reputation of being wild, crazy, and violent … drugs,” said Ullah, an alum of New Hope’ s Solebury Boarding School. “But [this] was during the Harlem Renaissance. My father talked about going to the Palladium and seeing Coltrane.”

Once the Bengali men jumped ship, they’d often travel to the Midwest, taking up jobs in steel mills in Youngstown, Ohio, or the auto industry in Detroit. “But one of the main steel mills where a lot of the ship jumpers worked was at Bethlehem Steel in Bethlehem, Pa., or the shipyards in Chester,” Bald said.

Inquirer journalists would report on the laskars’ food habits and rituals — taking note of their goat sacrifices, prayer practices, and hairstyles. “One of the strangest religious ceremonies ever witnessed in this city took place yesterday on board the German steamer Guthenfels when a live sheep was sacrificed in accordance with the rites of their faith in the presence of a crew of lascars,” reads a report from May 1906.

“It is then that you start seeing in the census records, entire groups of men from this population of ship workers,” Bald said. “In places like Harlem, often the men were categorized as Black. In Bethlehem, most of these South Asian men were working alongside immigrants from Eastern Europe. And the Indians were classified as white.”

The need to excavate this immigration history, Ullah said, is because there is little mention of it when we speak of South Asian history of America and, by default, American immigration history.

There is some writing on the North Indians who came to California in the early 20th century until the Immigration Act of 1917 (Barred Zone Act) was passed. “And then there was just this assumption that no one was here until 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act was passed,” Bald said. This act paved the path for “highly skilled” immigrants and professionals from India to come to the States.

“That law was written to favor engineers and doctors and professionals. What gets lost in that understanding of the South Asian American story is that ... in that entire period between 1917-’65, there was a sizable working class migration from South Asia to the U.S., but they were undocumented,” Bald said.

“When they were passing the Immigration Act of ‘65, my father’s friends wrote to [the] government saying, ‘While it’s great that you’re bringing in academics, please don’t neglect the working class, the people who are coming from places like Bangladesh or [other] third-world nations that need America as a place where they can also have an opportunity,” said Ullah, whose father worked in Indian restaurants in New York.

“These men were essentially stateless,” said Bald. “Their homeland was under British colonial rule and the United States had passed racist anti-Asian immigration laws that rendered them ‘illegal’ as soon as they set foot in the U.S. … It was African American and Puerto Rican communities that did welcome them, that lived up to the national promise of acceptance and inclusion.”

For Ullah, his family’s story is also one of finding community with African Americans and building solidarity. “South Asians in many ways were rescued and nourished and nurtured by African Americans, so that they could become Americans with dignity,” said Ullah.

“In Search of Bengali Harlem” is currently streaming on PBS’ World.

More information about SAADA’s Revolution Remix walking tour can be found on its website.