The Woodstock 50th anniversary and a decade of 1960s nostalgia: Thank goodness it’s almost over

We’ve nearly made it through. Our long national nightmare is almost over.

We’ve nearly made it through.

Our long national nightmare is almost over.

I’m speaking, of course, of the 10 years of pop cultural and historical nostalgia for the 1960s we’ve all endured as one world-changing event after another arrives on its half-century anniversary.

It’s 2019, so at long last we’re headed down the home stretch. We’ve been through the British Invasion and the Summer of Love. We’ve re-experienced The Vietnam War in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s marathon film for PBS. (And are looking forward to 16 hours of Country Music from them in September.)

Next up, it’s the moon landing, with Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s not-faked giant leap for mankind in July 1969 being commemorated.

And then, on to the big one: the 50th anniversary of Woodstock, the most mythic and idealized of all music festivals, which took place on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y., Aug. 16-18, 1969.

For a half-century now, Woodstock has been exalted as the apotheosis of the counterculture, the beautiful free love celebration that achieved peak Age of Aquarius.

As depicted once again in director Barak Goodman’s nostalgic new documentary, Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation (which is currently playing at the Ritz at the Bourse, but was made for PBS’ American Masters and can be seen on your TV in August) it’s a flower power and Wavy Gravy vision of gleefully getting naked and singing along to Country Joe & the Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag.”

From a 21st century experiential perspective, Woodstock looks like kind of a nightmare. Imagine being stuck with 400,000 others in a muddy field — with no cell phone! — gazing down at microscopic performers on a single faraway stage.

But in the memories of the festival planners and participants interviewed in Goodman’s doc — who are heard in voice over, but never seen in their current senior citizen state — Woodstock was an ecstatic music-fueled experience filled with only good vibes.

You wouldn’t know that any conflicts had arisen without being peacefully resolved, such as Abbie Hoffman interrupting The Who’s set to stage a protest and Pete Townsend hitting him over the head.

Instead, the fest is lovingly portrayed as what, by all account it largely was: a vast gathering of blissed-out just baby boomer (almost exclusively white) kids united by their love of music and opposition to the war — and fear of being shipped off to it.

It took place just a few short months before the bad acid would kick in at Altamont, the festival in California headlined by the Rolling Stones, at which four people died and which is commonly characterized as bringing the Sixties to a dark, demonic close.

The Woodstock weekend kicked off with Richie Havens strumming “Freedom” and ended three days later with a Jimi Hendrix set in which he famously detonated “The Star Spangled Banner,” on a trash-strewn hillside after most of the rained-soaked hippies had started home.

Even before the fest was over, the branding of Woodstock as a pure and perfect state of nature — 3 Days of Peace & Music — had already begun. Everything would once again be OK if we could only “get ourselves back to the garden,” as Joni Mitchell sang in “Woodstock,” the song she wrote while watching TV retorts about the fest from a New York City hotel room.

(Mitchell didn’t actually play Woodstock because her manager advised her to go on the Dick Cavett Show instead. She had, however, performed at the Atlantic City Pop Festival earlier in the month, along with many Woodstock acts and other luminaries such as B.B. King and Dr. John, the Night Tripper.)

The idea of Woodstock as a magical event has lingered, like the whiff of marijuana smoke over the culture, five decades on. And yes, there is a newly minted Woodstock Cannabis Co., branded with the original white dove logo, offering “Peace,” “Love” and “Music” strains of weed.

Michael Lang, a Woodstock organizer, was involved in producing anniversary editions of the fest in 1994 (mostly mediocre and muddy, but fun, I was there) and 1999 (Limp Bizkit-y and on fire, I wasn’t, thank goodness).

And Lang is trying mightily to pull off another iteration, this time in Watkins Glen, N.Y., in August. As of this writing, Woodstock 50 seems doomed, despite an announced lineup that mixes such big-name acts as Jay-Z, Miley Cyrus and Imagine Dragons with a smattering of old heads such as Santana, Melanie and Canned Heat.

Tickets have yet to even go on sale, and after investors pulled out in April, the racetrack where it was scheduled to be held terminated the site license. It seems as if it would take a miracle for the fest to take place, though it’s worth remembering that the original festival was also kicked off its original site and only found Yasgur’s farm at the last minute.

That was fortuitous, Goodman’s film points out, because the 600-acre natural amphitheater was ideal, and organizers couldn’t get it together to put up a fence around in time. Which meant that when far more than the 100,000 or so expected showed up in hopes of buying sold out $8 a day tickets, there were no barricades to break through.

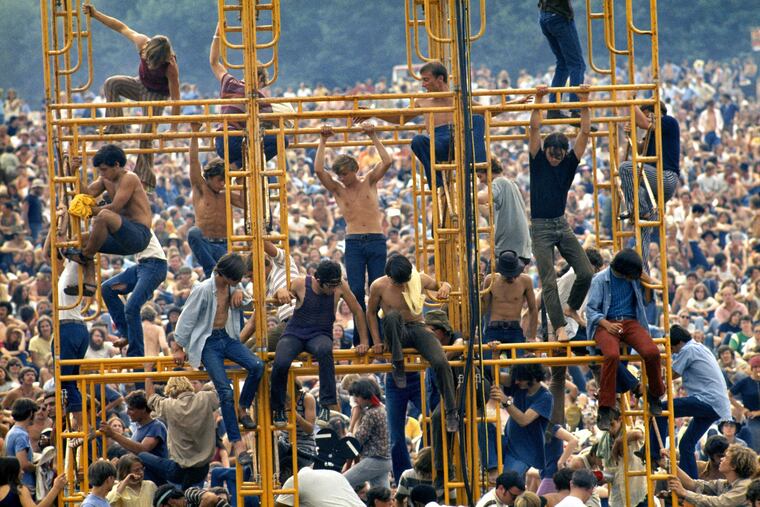

It’s the sheer size of Woodstock that still can blow you away, as the camera pans the crowd in either Goodman’s film, or Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 superior Woodstock. Mitchell was exaggerating when she sang, “by the time we got to Woodstock, we were half a million strong,” but not by that much.

And in many ways, that’s the real story of Woodstock as a cultural force. The crowd might have believed itself to be an anti-capitalist free-to-be-you-and-me movement, content to eat a free breakfast of oats and honey served by members of Wavy Gravy’s Hog Farm commune.

But the scale of Woodstock, and the media attention it gathered made the long haired boomer generation impossible to ignore. And they’ve been making sure that we don’t ever since.

The big secret of the concert business is people go to shows as much to see each other as to see the bands up on stage. You go out to find your people, and at Woodstock, people realized that there was a whole upstate New York hillside worth of people just like them.

At the time, the concert business was just beginning to take shape, and Woodstock signaled what a gigantic billion dollar enterprise it could become. In the early years of the 1970s, huge events of a Woodstock-inspired scale were’t uncommon. In 1973, Summer Jam at Watkins Glen attracted 600,000 people. And in 1976, a Bicentennial Concert at JFK Stadium featuring Yes and Peter Frampton drew 130,000 to South Philadelphia.

The Woodstock myth derives from the sense of purity that surrounds it, its peace and love essence and the creation of an alternate environment away from the hustle and bustle of commerce.

But its spread as a cultural force is a media driven, commercial experience. The existence of Woodstock as the classic music film of the era — a perennial favorite of the midnight movie screening — allowed boomers and subsequent generations to experience the festival again and again right up close.

The great majority of people actually at Woodstock were football fields away from the performers. But the intimacy of movie cameras allowed the legend to grow further. The scene of Sly & the Family Stone waking the crowd up with “I Want to Take You Higher” was achieved in Wadleigh’s film with cameras held close to the performers faces. Cranky Neil Young has complained the allegedly idyllic experience was corrupted from the get go.

Though the crowd at Woodstock was demographically monolithic — and really skinny — it’s been held up as if it were a shining beacon of Utopian symbolism.

And that’s part of Woodstock 50′s sales pitch about how it can be relevant once more, calling itself “a cultural icon that changed the way we think about music and togetherness … and will do so again.”

Will it? It seem more likely that the 2019 version of the festival won’t even happen. And in the fractured nation that we live in today, that seems fitting and appropriate. We’ve had more than enough ’60s nostalgia already, but if we must endure a little more, the dark and disturbing 1969 anniversaries that are still to come like the Manson Family murders and Altamont seem more in keeping with the country’s mood. We’re a long way from getting back to the garden.