The Broad Street Bullies were almost the ‘Blue Line Bandidos.’ They had other nicknames, too.

Here’s the story behind how Philadelphia Bulletin sportswriter Jack Chevalier coined the Flyers’ famous nickname.

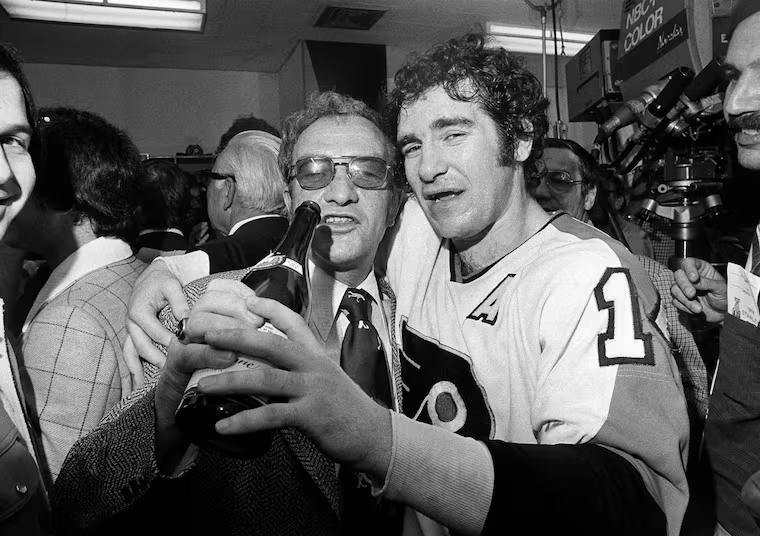

The Broad Street Bullies moniker has been around almost as long as the Flyers themselves. More than 50 years after the nickname was first coined, it is still synonymous with the franchise. Even though all of those 1970s Flyers have long since retired from the NHL, the Bullies’ legacy remained at the forefront of the team’s identity for years as many remained close to the organization — or in some cases right at the very top of it.

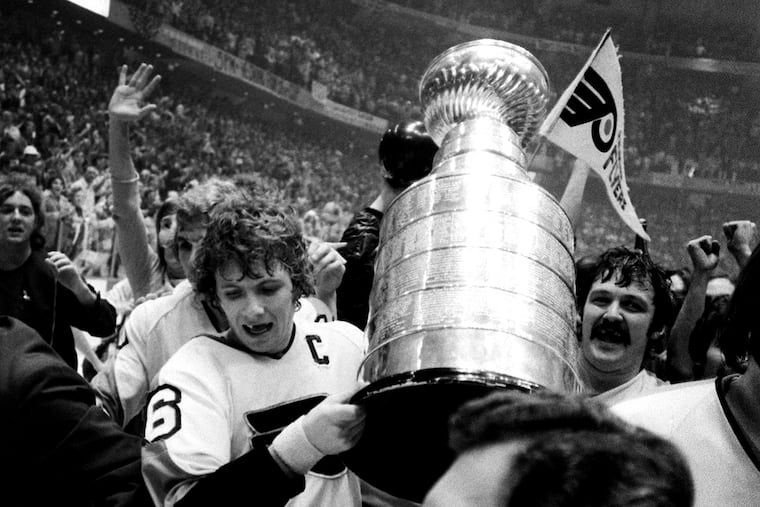

So while the majority of Philly fans weren’t alive to witness those teams, the Broad Street Bullies are still lionized in franchise lore, even after the Flyers embarked on a “New Era of Orange.” As we near the 50th anniversary of their first Stanley Cup title, we take a look back at the origins of their iconic nickname — and how it almost never came to be …

Who invented the Broad Street Bullies nickname?

Philadelphia Bulletin writer Jack Chevalier coined the phrase during the 1972-73 season, the year before the Flyers’ first Stanley Cup win. He later wrote a book titled The Broad Street Bullies: The Incredible Story of the Philadelphia Flyers in 1974 after the Cup victory.

Why were they called the Broad Street Bullies?

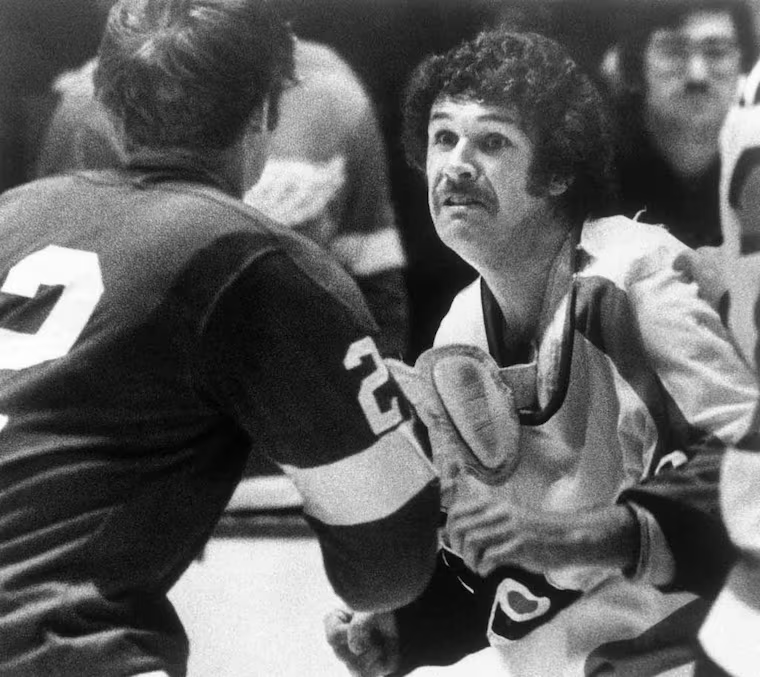

The Flyers were notoriously tough in the early 1970s, never afraid to drop the gloves. Nine Flyers recorded more penalty minutes than games played during that 1972-73 season, including five with twice as many penalty minutes. In their first Stanley Cup season (1973-74), seven Flyers racked up more than 100 penalty minutes. And the following season, the notorious fighter Dave Schultz set the single-season NHL record for penalty minutes (472), a mark that still stands.

» READ MORE: With the Flyers locked in at No. 12, here are 8 players to know ahead of the 2024 NHL draft

The Broad Street Bullies moniker highlighted the grit and toughness of the Flyers’ championship teams, but they were also one of the NHL’s most skilled teams during that era. Bobby Clarke, no stranger to the penalty box himself, posted 87 points, the fifth-highest total of any player during the 1973-74 season, and Rick MacLeish wasn’t far behind with 77 points, also in the top 20 in the NHL.

“Were we overlooked on the skill side? Yeah, that was evident,” former Flyer Terry Crisp told The Inquirer. “But you know what? We said, ‘You know what, that’s fine. We’ll hide that. If they don’t think we have any skill, that’s fine. Let them think we don’t have skill until all of a sudden it jumps up and bites them in the [butt].’”

When did the phrase first appear?

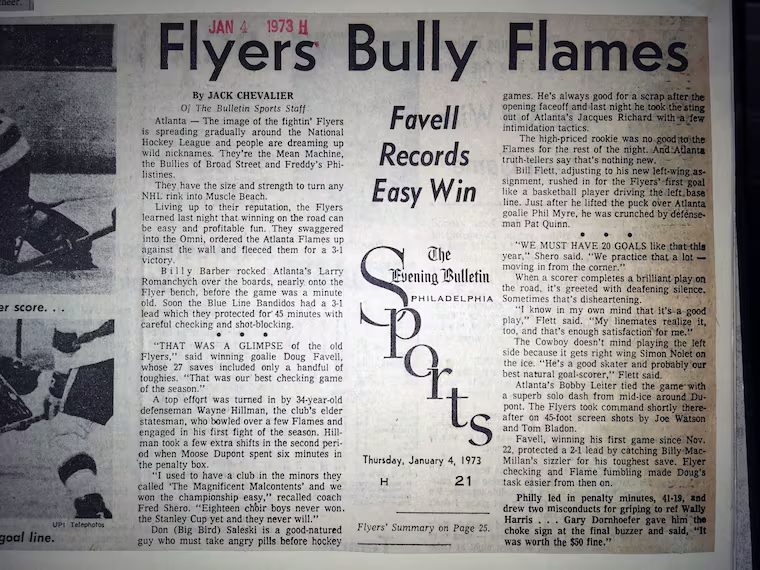

The phrase — at least a version of it — appeared in Chevalier’s game story following the Flyers’ 3-1 win over the Atlanta Flames on Jan. 3, 1973. But the nickname initially looked very different. Former Inquirer sportswriter Sam Carchidi shared the story of how the famous nickname ended up on the pages of the Bulletin in Chevalier’s obituary in 2019.

According to the obituary, he chose the nickname the “Blue Line Bandidos” — despite the old Spectrum being located off the “Orange Line,” the original name for the Broad Street Line. Chevalier later ditched the hockey reference — no, it wasn’t a reference to SEPTA’s original name for the Market-Frankford Line — and updated it to “Bullies of Broad Street.” His copy editor, Pete Cafone, said he eliminated the “of” and rearranged the words to Broad Street Bullies to fit the print headline, and the new nickname was born.

But in the original copy of the Bulletin story, which was provided by the Flyers, both “Blue Line Bandidos” and “Bullies of Broad Street” are referenced as though they were common Flyers nicknames, with neither as the headline on the page. Instead, the headline on the first edition read “Flyers Bully Flames.” The specific phrase “Broad Street Bullies” doesn’t appear in the copy.

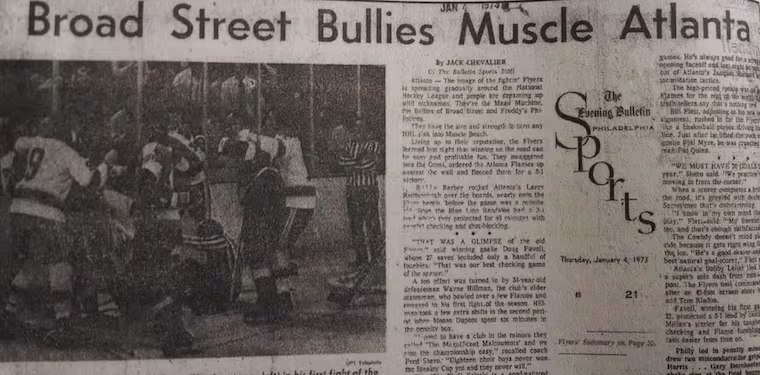

UPDATE: Thanks to Cafone and the Flyers, we’ve located the first reference to “Broad Street Bullies.” “Broad Street Bullies Muscle Atlanta” was the headline of that game story in a second edition of that day’s Bulletin, which featured an additional photo, with much of the same copy as the earlier version of the story.

From that story, spawned a nickname that would last for decades.

What were some other potential nicknames?

Initially, there were a number of different nicknames used by writers of the era to describe the team.

Just over a month after Chevalier’s story in the Bulletin, a Feb. 15, 1973 article in the Boston Globe said that the Flyers “had come to be known with much affection as the Broad Street Bullies.” The nickname’s first reference in The Inquirer came just a few days later, on Feb. 18, as just one in a list of nicknames for the team, also including “Freddie’s Phillistines, the South Philly Saracens, and the Mad Squad.”

Other papers, such as the Minneapolis Star, also referenced the Mad Squad, a riff on The Mod Squad, a popular television show that ran from 1968-73. Daily News sportswriter Bill Fleischman wrote in March 1973 that he preferred the Mad Squad moniker to Broad Street Bullies, but many of these alternate names have been forgotten.

When did Broad Street Bullies catch on?

By the time the Flyers won the 1974 Stanley Cup, “Broad Street Bullies” had spread far past the pages of the newspapers and into opposing locker rooms.

“That stuff about the Broad Street Bullies, forget it,” the Bruins’ Wayne Cashman told The Inquirer in 1974 after the Flyers beat them for the Stanley Cup. “They’re just pretty damn good hockey players.”

Phil Esposito was less generous toward the phrase.

“You guys made up that name, not the team,” Esposito told The Inquirer in 1974. “Like calling us the big, bad Bruins. They just play the way they think will win for them.”

» READ MORE: 5 key questions facing the Flyers as they begin an interesting offseason

Thanks to the modern NHL rule book, it’s no longer possible to be as tough as those old-school Flyer teams. Now, as the Flyers celebrate the 50th anniversary of the franchise’s first Stanley Cup win, new leadership is focused on a “New Era of Orange.” Part of that new era will mean carving out the Flyers’ modern identity.

“They don’t want to be Broad Street Bullies,” Crisp said. “We made our footprints. Their belief is, ‘We want to make our own footprints.’ You can’t go back in history. You can’t go back in time. You can’t duplicate that feeling we had when we skated out on the ice and our fans went nuts.

“We swaggered out onto the ice in the other teams’ buildings and they’d go crazy against us. You can’t bottle that. That was once in a lifetime, for us and our fans.”