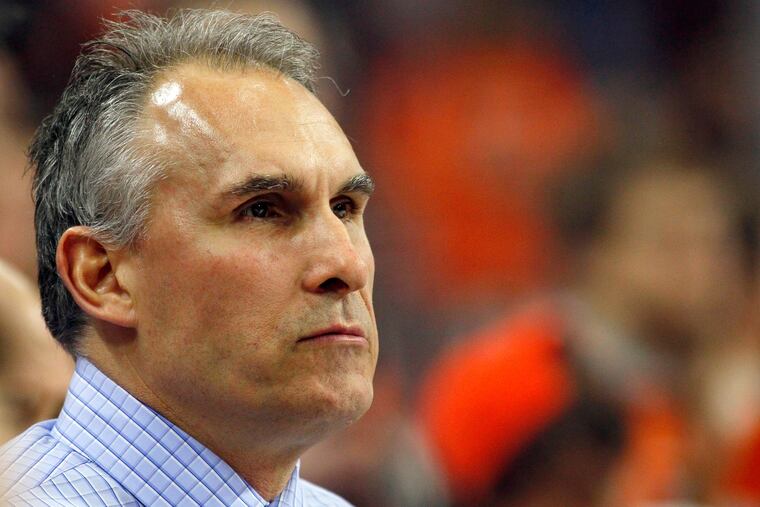

Craig Berube could win a Stanley Cup with the Blues. Relax, Flyers fans. It wouldn’t have happened here. | Mike Sielski

The Flyers had, and still have, problems that go beyond who their head coach is or was.

Would everything have been different for the Flyers if they hadn’t fired Craig Berube?

It’s a natural question to ask, now that Berube has coached the St. Louis Blues to their first Stanley Cup Final since 1970, now that they enter Game 1 against the Boston Bruins on Monday night with a chance to win the first championship in their 52-year history. And their accomplishment – and Berube’s – is made even more impressive for knowing that on Jan. 3, six weeks after Berube replaced Mike Yeo as their head coach, the Blues had the worst record in the NHL.

It’s a marvelous story already, one that would be made better if the Blues upset the Bruins, and you can hardly blame a loyal Flyers fan for ruing, retroactively, then-general manager Ron Hextall’s decision to fire Berube after the 2014-15 season. Maybe everything would have been different. Wouldn’t everything be different?

No, it probably wouldn’t. It’s convenient and comfortable to think that it would be, because it’s always convenient and comfortable to think that a complex problem that has remained unresolved for a long time – i.e. the Flyers’ mediocrity – might have been solved with a single simple alteration to the past. The Flyers shouldn’t have traded Jeff Carter and Mike Richards. They shouldn’t have gotten Ilya Bryzgalov or gotten rid of Sergei Bobrovsky. They shouldn’t keep Paul Holmgren. They shouldn’t have hired or fired Hextall. They shouldn’t have fired Peter Laviolette or Berube. They never should have drafted Nolan Patrick. They never should have let the name “Dave Hakstol” pass their lips.

But as a wise Texas sheriff correctly notes in the film No Country for Old Men, it’s never the one thing. It’s the dismal tide. It’s an overriding philosophy, with the exception of Hextall’s four-plus years as GM, that the present is always more important than the future. It’s a nine-year period of drafting that produces just three players of significance to the organization. It’s a refusal to accept that bad trends over long periods might take just as much time, if not more, to reverse. Amid that environment, that culture, even a solid coach, one who might turn out to be capable of winning a Stanley Cup, can make only so much of a difference.

At the time the Flyers hired Berube, I criticized them for it. Soon after, he and I were involved in a question-and-answer exchange that led to his telling me to “get lost,” which established a popular perception that we were enemies. That narrative was always false. Berube generally did a good job as the Flyers’ coach, and he was nothing but a professional to deal with thereafter. (We ran into each other years later at a Gap Kids in Bucks County and had a perfectly cordial chat near the overalls rack.)

My objection to his hiring was never about him per se, anyway. It was about the Flyers’ reflexive tendency to act as if a surface change – making a trade; signing a pricey free agent; bringing in a new coach, often one with longstanding ties to the organization, like Berube – would fix all their troubles. Anyone with eyes to see should have been looking for the Flyers to acknowledge that the solution they needed was bigger, bolder, and broader than all the others they’d routinely tried before and, in replacing Laviolette with Berube, were trying again.

In Berube’s second season as their coach, and Hextall’s first as their GM, the Flyers went 31-33-18 and missed the playoffs. Their top four defensemen, in games played, were Mark Streit, Michael Del Zotto, Nick Schultz, and Nicklas Grossman. Their forwards included veterans in decline (Vinny Lecavalier, R.J. Umberger), youngsters still growing (Sean Couturier, Brayden Schenn), and journeymen (Matt Read, Chris VandeVelde). They still had major salary-cap issues. It was a classic example of a roster that needed to be rebuilt – and a default action plan that needed to be ripped up and rewritten.

For whatever mistakes he made, either in his player-personnel decisions or his interpersonal interaction with his coworkers, Hextall understood that. In the choice between trying to catch lightning in a bottle – like the Blues did this season, like the Flyers did in 2010 – or trying to achieve and maintain a particular level of success, Hextall pursued the latter. He created some cap flexibility and replenished the organization’s talent pool. These were necessary measures, and they took time. Now that he’s gone, it remains to be seen whether he did enough to allow the Flyers to reach that goal and whether the team’s new brain trust will follow or deviate from that approach. That’s the key question, and no matter how Craig Berube and the St. Louis Blues fare in this Stanley Cup Final, it’s a much more important one for the Flyers than who their head coach is or has been.