A global HIV vaccine trial with ties to Penn ended early, but local scientists remain optimistic

The study is the latest unsuccessful effort to create a vaccine against HIV.

The only HIV vaccine clinical trial in advanced stages has ended early after data showed the shots didn’t prevent infection.

The late-stage, international vaccine trial was led by Janssen Pharmaceutical — part of Johnson & Johnson — in partnership with clinics all over the world, including at the University of Pennsylvania.

Those involved in the study are disappointed that yet another effort for combating a virus that infects about 35,000 Americans a year fell short. But local scientists are optimistic that lessons learned from this study could advance new, unexpected solutions to other health challenges.

“Even though we don’t have an HIV vaccine yet, all of the science that has been done over the last 20, 30 years, trying to get an HIV vaccine, has yielded incredible benefits in other areas,” said Ronald Collman, the director of the Penn Center for AIDS Research, which is an umbrella organization that includes the HIV Prevention Trials Unit that ran the study locally.

Why it’s so hard to create an HIV vaccine

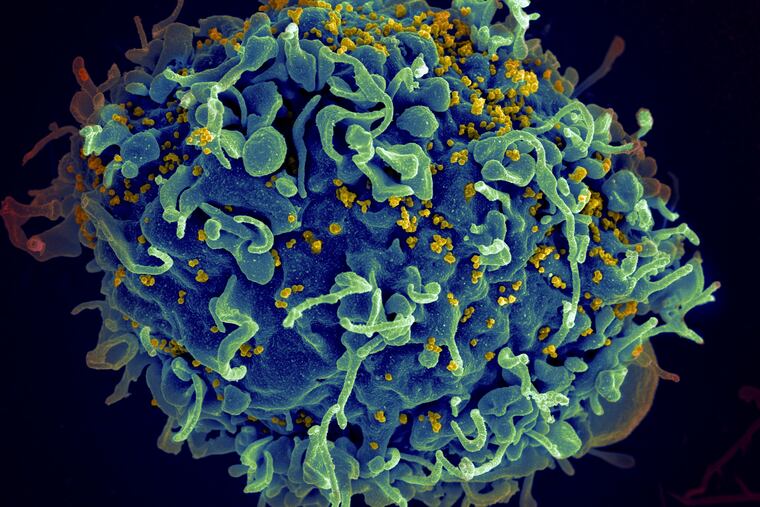

Creating a vaccine that’s effective against HIV is difficult because of the way the virus is built, Collman said. The virus has a protein coating that’s difficult for antibodies to attach to. HIV and its protein shell mutate often, which complicates efforts to design a vaccine that will be effective against each new iteration.

Researchers have been able to generate antibodies to a single variation of HIV, but vaccines that protect against only one variation aren’t useful when there are so many variations of the virus circulating.

» READ MORE: Penn scientists made a universal flu vaccine using mRNA, and they plan to test it in humans

Janssen was attempting to develop a vaccine that could recognize many different HIV strains. The trial simulated a strain of HIV that included little pieces from many of the HIV strains known to be circulating. No matter what mutation the virus has, the antibodies of a vaccinated person would know how to attach to part of it, scientists hypothesized.

“It’s a mosaic of many different HIV strains,” Collman said.

Hence the name of the study: Mosaico.

Phase 3 of the Mosaico study began in 2019. More than 50 trial sites enrolled about 3,900 cisgender men and transgender people who have sex with men or other transgender people.

Participants got multiple shots and also had blood drawn to test for antibodies and HIV. In return, they received a small stipend.

Advocating for clinical trials and HIV prevention

Zachary Hall, a 35-year-old Philadelphian who works for a medical distribution company, was interested in enrolling in the study both because of his background in public health and the way HIV touched his life.

Hall’s great-uncle died of HIV/AIDS in the late ‘80s. Decades later, in 2011, Hall joined the Peace Corps and spent two years in Mozambique, where he taught sex education. After his return to the United States, he earned a master’s in public health.

Because of his experience and public health education, Hall felt comfortable that he isn’t taking a risk by signing up for the trial, and he did in early 2020. He also knew it might not work.

Two years ago, J&J halted a similar HIV vaccine trial in South Africa.

“I wasn’t surprised,” Hall said.

Even though he didn’t get to be part of the successful effort that researchers hoped for, Hall said that he hopes people continue to sign up for trials.

“Doing studies can be really rewarding even though it didn’t pan out,” he said.

» READ MORE: A new Philly HIV prevention program will make PrEP medication available for free — with no in-person visits

While the Mosaico study didn’t end successfully, it isn’t a failure yet, Collman said. Science builds up, and often, lessons from one effort can be applicable at another unexpected moment.

For example, decades ago researchers at Penn experimented with mRNA technology in their attempt to develop a HIV vaccine. Those efforts haven’t panned out yet and are still ongoing, but they advanced a technology that later would be ready to quickly create an effective COVID-19 vaccine.

In the meantime, Collman urged people to consider other ways to reduce their risk of acquiring the virus. Pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, is a medication that dramatically cuts the risk of HIV from sex by as much as 99%.

“We actually do have a really good way of preventing infection, and that’s PrEP,” he said.