A CT scanner on wheels? That’s the dream of this Philly physician who heads an ARPA-H program.

Bon Ku, a former Jefferson Health physician, envisions a mobile health clinic that could help patients in rural and urban areas.

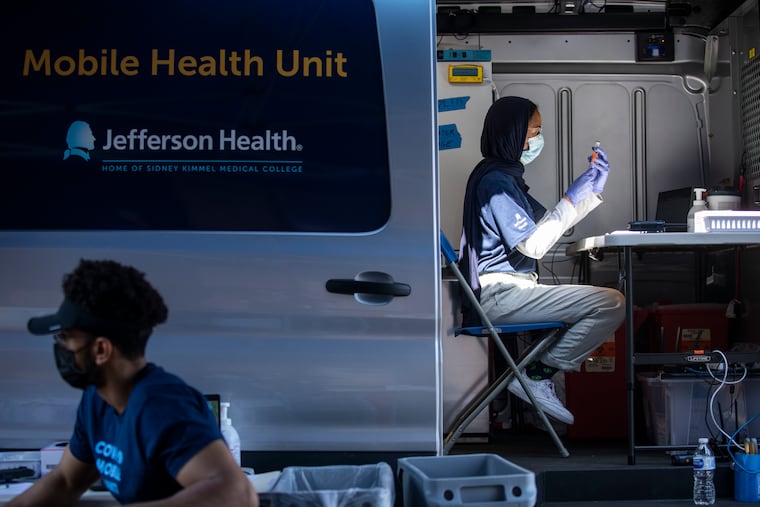

Physician Bon Ku kept hearing the same thing from Philadelphians who got a COVID vaccine at one of Jefferson Health’s mobile health clinics: If the van had not come to their neighborhood, they would not have gotten the shot.

That made Ku wonder if he could offer a lot more than vaccines, equipping a vehicle with advanced hospital equipment such as a miniature CT scanner.

Ku plans to make it happen now that he has left Jefferson to join ARPA-H, the new federal agency for health care research.

This month, he and the agency launched a national, five-year program to create a next-generation mobile health vehicle, aimed at reaching patients with limited access to a hospital. The agency is seeking proposals from companies and academic researchers to design a wide array of functions in such a vehicle, including a mini CT scanner, lab and diagnostic equipment, and a satellite hookup for real-time videoconferences with hospitals.

“It’s really like a Swiss army knife platform that can deliver a wide variety of services,” he said.

Rugged vehicles

The primary goal of the program is to reach rural areas where poor hospital access contributes to high death rates from cancer, heart disease, and other chronic conditions. More than 100 hospitals in primarily rural areas have closed in the past decade, according to ARPA-H, which was created in 2022 by the Biden administration as an independent unit within the National Institutes of Health.

That’s why one of the design requirements is to make the mobile health vehicles “ruggedized” — able to travel bumpy dirt roads without damaging the high-tech equipment inside.

In theory, these vehicles also could be deployed in urban areas with poor health outcomes, including parts of the Philadelphia region, where Ku still lives. While the ruggedness of the vehicle would matter less for city usage than in rural areas, its mobility would benefit anyone who has trouble getting to a hospital, he said.

Ku said he learned that lesson from the mobile COVID vaccine clinics run by Jefferson and other health providers. Many were stationed in neighborhoods that are home to lower-income residents of color, some of whom who might otherwise not have gotten vaccinated due to lack of transportation, time, or trust in the health-care establishment.

The challenge of CT scans

Mobile health clinics have long provided specialized care beside vaccines. Vision exams, cardiac stress tests, and some kinds of cancer screening have all been administered from specially equipped vans or buses.

The vehicles that Ku envisions would combine all of the above and much more.

ARPA-H, where he is now a program manager, is holding an event in February to share more details about the plan with interested researchers and companies. Design proposals are due by April 26. Later in the year, the agency plans to select winners in five categories, spanning various elements of hardware and software needed for the vehicles.

Each will then receive funds to build a prototype of its portion of the vehicle. Ku declined to reveal the total amount of money that is potentially available, saying the agency did not want to constrain designers’ creativity in the initial stages. Still, entries will be judged on cost effectiveness, among other variables.

A key challenge is to design a miniature CT scanner. Traditional CT machines are far too heavy and cause too much vibration to mount on a vehicle, said Ku, an emergency medicine specialist and the former director of the health design lab at Thomas Jefferson University.

Other design categories include a broadband hookup for real-time communication with hospital personnel, and a software platform that integrates the vehicles’ devices with each other and with patients’ electronic health records.

The program specifications do not spell out all the types of health services that would be offered in the mobile health clinics, but Ku envisions that they would include dialysis, maternal health care, and an array of lab and diagnostic tests.

Meanwhile, ARPA-H also has started to seek proposals to tackle a variety of other health care challenges, including eye transplants and preventable deaths.

The agency is modeled after DARPA, the research arm of the Pentagon. It has a decentralized structure with “hubs” and “spokes” located throughout the country. In September, Philadelphia’s University City Science Center was named as a spoke for a hub based in Dallas, which is focused on reducing health disparities.

The agency is designed to identify and develop treatments for cancer, Alzheimer’s, and other diseases much faster than other NIH divisions, which fund research that can last for decades.