Could fixing autophagy hold the key to preventing brain diseases?

This cellular recycling process declines with age, possibly making us more vulnerable to neurodegenerative diseases. A Penn team has found a possible place to target repairs.

Penn Medicine scientist Erika Holzbaur studies a tiny world: the parts of individual cells and how they work together. Her most recent work suggests that the way our brain cells manage waste products — a process known as autophagy — declines as we age, which could be a factor in dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases that become more common with age.

In mice, her lab has found in a recent study what may be a new target for medication, one that could keep brain cells operating smoothly longer.

What her work doesn’t do, she said, is add evidence to internet-fueled theories that individuals can harness autophagy themselves by, for instance, fasting, to prevent dementia.

The study from Holzbaur's lab was published in July in the journal eLife. The first author is Andrea Stavoe, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab.

Autophagy — most often pronounced aa-TAA-fuh-jee — is like a cellular recycling program that allows neurons to disassemble worn-out parts, then rebuild them. The word means “self eating.” When the process doesn’t work properly, toxins can build up and kill cells. That’s particularly bad in the brain because your body doesn’t make many new neurons.

The Penn team was interested in how autophagy changes with age because defects in the process are associated with multiple late-onset diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases. It seemed likely that autophagy stopped working as well as mice got older, and that’s what the study found. “What surprised me is how strong a decline it is,” Holzbaur said.

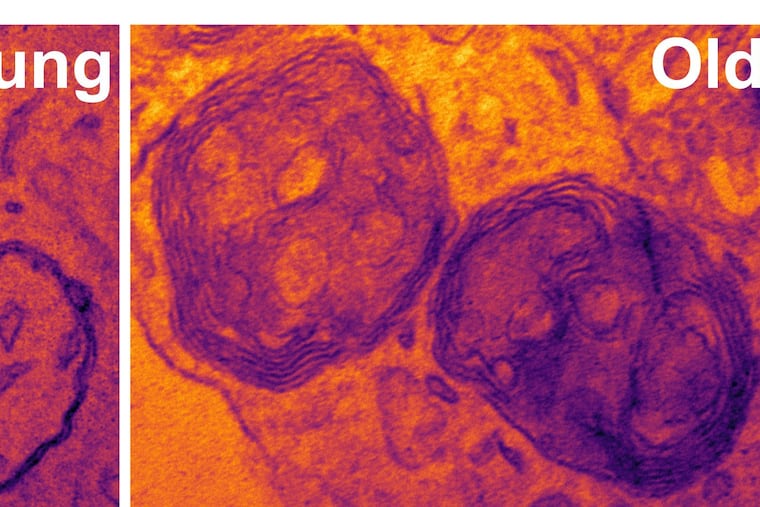

The biggest problem was in a structure called an autophagosome, a cell component that engulfs damaged proteins, then fuses with another structure called a lysosome that breaks down the garbage. Aged mice produced fewer autophagosomes as well as more defective autophagosomes.

Most important, within a cell (not a whole mouse), the team was able to replace a protein that wasn’t working properly called WIPI2B and restore proper autophagosome formation. Its method would not be practical in a living organism but points to a target for drugs, Holzbaur said.

"We haven't gone anywhere near that yet," she said. "It does offer hope that this might be a way to protect neurons from this age-dependent degeneration."

She doubts that problems with autophagy are what actually cause neurodegenerative diseases or that fixing autophagy would cure them. However, the process may be able to keep some diseases at bay when it is working well. Keeping it well-tuned in older people might delay the onset of disease by a couple of decades, she hypothesized.

Attempts to popularize the idea that fasting and calorie restriction can rev up autophagy largely rest on studies of how the process works in cells outside the brain such as muscle cells, she said. The evidence so far is that autophagy works differently in the brain. It may even have a role there in memory and learning.

Starving yourself is not likely to prevent dementia, she said, although there is reason to believe that obesity is bad for the brain. So far, “nothing we’ve done has been able to enhance autophagy in neurons,” she said.

That leaves all the people who’d like to protect their brains with the usual health advice, Holzbaur said. Don’t smoke. Don’t drink too much. Eat healthy food and exercise.