Breast reconstruction mesh may increase risks after mastectomy. FDA looks for answers.

Many surgeons believe reconstructive breast surgery is improved by using a skin substitute to cradle implants. But surgical mesh may actually increase complications, and the government is grappling with how to tighten its oversight.

For women who blame their chronic illnesses on breast implants, a huge outrage is the fact that manufacturers have failed to do government-ordered studies intended to get data on those illnesses.

But silicone implants aren’t the only devices that haven’t been adequately tested in breast surgery.

For more than a decade, plastic surgeons have been using a high-tech, bioengineered skin substitute to cradle implants that reconstruct the breasts of mastectomy patients. Every year, about 72,000 cancer survivors have this so-called surgical mesh installed in their bodies. Surgeons say the product makes for faster healing and better results.

But mounting evidence shows that the costly material — as much as $3,700 for a patch slightly bigger than a cell phone — may be harming women. Higher rates of postoperative complications have been linked to the mesh, including major infections, pools of swelling around the implant, and reconstructive “failures,” meaning the implants have to be removed.

Last week, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration advisory panel that revisited the issue of implant safety discussed what to do about surgical mesh. In light of potential dangers — and because manufacturers now want to market the product for cosmetic breast surgeries such as lifts and reductions — the FDA has told them they have to do studies assessing safety and effectiveness.

But the FDA isn’t sure what kind of studies to require. And if history is any guide, getting manufacturers to do costly research on entrenched products won’t be easy. The FDA is still struggling to make companies do studies, first mandated in 2006, to address the decades-old question of whether implants increase the risks of autoimmune symptoms and diseases, now called “implant illness.”

Panel member Howard Sandler, a radiation oncologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said: “For better or worse, the [mesh] products are already on the market, so manufacturers may not be highly motivated to do testing. It’s almost like the cat is out of the bag. It may be too late to try to get clinical trials.”

Surgery evolves faster than the science

Breast implant illness and breast implant lymphoma – a very rare immune system cancer that the FDA first warned about in 2011 – dominated the advisory committee meeting last week, with scores of women sharing stories of their suffering. The advisers, who offered guidance but made no formal recommendations, were not in favor of banning rough-surfaced implants, the type linked to almost all of the nearly 700 worldwide cases of implant lymphoma.

But for the first time, there seemed to be a consensus that in some women, implants can trigger a chronic inflammatory reaction that produces symptoms ranging from fatigue and pain all the way to the lymphoma. The panel favored strengthening the informed consent process to warn women of the risk.

“At a minimum, the FDA could say implant illness is a real entity that needs further study,” said panel member Benjamin Anderson, a professor of surgery at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

Surgical mesh was a smaller, but equally thorny, part of the discussion.

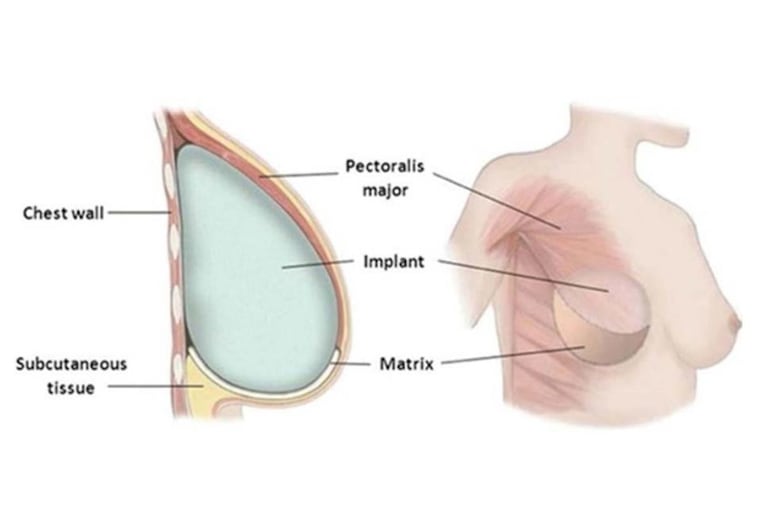

Panel member Pierre Chevray, who specializes in breast reconstruction at Houston Methodist Hospital, pointed out that the term “surgical mesh” is unclear. The products, derived from human, pig or cow skin, are technically called acellular dermal matrix (ADM). Placed in the body, the matrix is gradually absorbed and becomes part of the patient’s tissue.

Allergan, a maker of popular breast implants, also manufactures Alloderm, a leading mesh brand. Other brands include Surgimend (Integra Lifescience), Allomax (C.R. Bard), and Flex HD (MTF Biologics).

“Allergan is committed to the generation of additional data supporting ADM in breast reconstruction,” Allergan’s associate vice president, Stephanie Manson Brown, told the panel.

Biological meshes are not the same as synthetic pelvic mesh, made of non-absorbable plastic fibers and used to support weakened abdominal organs. The FDA has tightened regulation of the synthetic device amid a deluge of reports and lawsuits alleging problems including pain, bleeding and infection.

Both biological and synthetic meshes originally came on the market under a much-criticized approval pathway known as 510(k). It allows diagnostic tests, surgical machines, heart valves, and other potentially risky devices to be “cleared” by submitting scientific evidence that they are equivalent to devices already on the market.

The FDA cleared biological mesh for other kinds of plastic and reconstructive surgery before it was ever used in breast reconstruction.

In theory, using mesh to help rebuild breasts has advantages. Reconstruction is usually a two-stage process. First, a silicone pouch called an expander is put under the chest wall muscle and gradually filled with fluid over weeks or months to create a pocket. Then the expander is removed and the implant is put in the pocket.

By sewing a piece of mesh to the muscle to create a sling or hammock under the implant, the expansion process can be abbreviated or even eliminated, and a bigger pocket can be created.

Surgeons and manufacturers claimed the mesh shortened surgical time, decreased pain and recovery time, and made the implant look and feel more natural.

Then this practice evolved. As Chevray explained, surgeons began wrapping the whole implant in mesh and placing it on top of the chest wall muscle, directly under the skin. With a bare implant, under-the-skin placement can look unnatural and cause skin hardening.

Encasing the implant adds many thousands of dollars to reconstruction, which is covered by health insurance.

Even though this newer technique hasn’t been well-studied, it is catching on, Chevray said, because “the manufacturers of the meshes market them very heavily. Surgeons are heavily compensated to speak about using mesh.”

What patients really think

Meanwhile, studies have found that the under-the-muscle sling approach — now used in 80 percent of reconstructions — increases infections, swelling, and reoperations.

“Most investigators have found there are additional risks" with mesh, said plastic surgeon Edwin Wilkins, a breast reconstruction specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Wilkins was the senior author of a government-funded, 10-center study of about 1,300 women that looked at complication rates with and without mesh, as well as a rarely measured aspect: patient satisfaction.

Wilkins told the panel that mesh made no difference in complication rates — until the researchers looked at rates for each of the four products used in the study.

“For two brands, complications were significantly worse – three to four times worse,” Wilkins said without identifying them.

In an interview, he declined to specify the outliers because the manufacturers have threatened to sue him if he does.

Women in the study filled out detailed questionnaires at four time points up to two years after surgery, rating their pain, their breasts, and their physical, emotional, and sexual well-being. To Wilkins’ “shock,” mesh had no effect on patients’ satisfaction.

And even though mesh is touted as reducing the need for chest muscle expansion, it shaved just six days off the process.

“Now that we have these results, I have to rethink what I do,” Wilkins said. “I really do think I get better results with [mesh]. But that’s the surgeon’s point of view. I’m pretty sure that’s not the view that counts. I totally acknowledge that.”