As pressure from the pandemic wanes, health-care workers cope with burnout and a fractured community

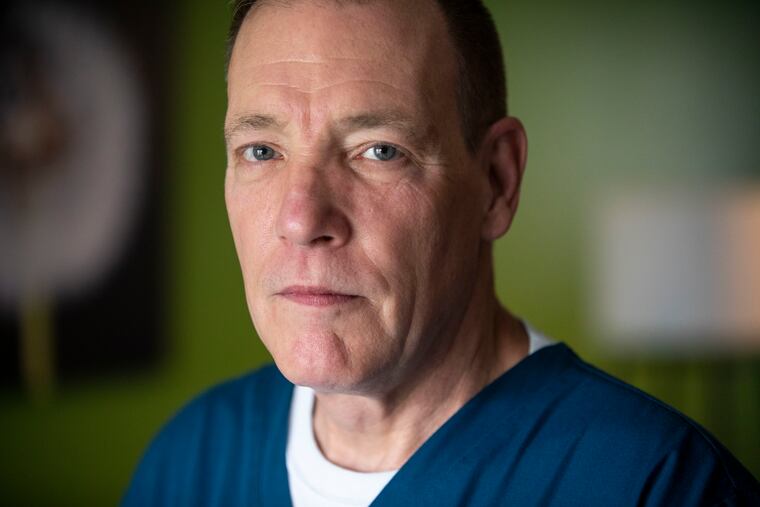

“If I start talking about it, and I start to think what it was like, then it affects me,” said a nurse at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Langhorne.

Patients with COVID-19 aren’t filling hospitals anymore. Fears of bringing the virus home and infecting loved ones has largely passed.

For Bill Engle, though, a nurse at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Langhorne, the emotional wounds inflicted by the pandemic remain close to the surface.

“If I start talking about it, and I start to think what it was like, then it affects me,” he said, his voice cracking. “Every day going in to work and knowing I was going to be in that N95 and seeing these people struggle and how scared they were and the physical toll that they took, it was next level.”

He is hardly unique.

Interviews with doctors and nurses around the region revealed a sense of relief over a waning pandemic leavened by fears that the virus could surge again. They use different terms to describe what almost a year and a half of being on the front lines of treating COVID-19 has done. Moral injury. Trauma. Burnout. PTSD.

“I think it’s changed most of us forever or for a very long time,” said Carla LeCoin, a maternal-health nurse at Einstein Medical Center, “whether it’s how we practice, how we look at our upper management, how we look at the public, the government.”

In the rush to tackle a new and frightening virus, health care workers were buoyed by urgency and a sense of shared purpose. But it’s easing has left them with time to reflect on the death and sickness they witnessed, the anxieties of long hours and insufficient safety protections. Now they wonder whether COVID-19 is truly in retreat.

“If you’re living on that adrenaline rush for a while, and then that starts to go away, then the reality sinks in,” said Marc Moss, a doctor and researcher at the University of Colorado who studies mental health in health care workers. “You can overcome a lot of things in the heat of the moment but it’s still taking an emotional toll.”

The consequences of burnout among health care workers go beyond their own well-being. It can lead to an increase in medical errors and worse quality care for patients, Moss said. That reality was one of the factors that led the health care field to focus more seriously on practitioners’ wellness about two decades ago. Yet, the pandemic laid bare that work remains to be done.

Though COVID-19 cases have dropped in the region, drained health care workers must still maintain a busy schedule as hospitals face a glut of patients who had put off health care out of fears of contracting the virus.

“Even though the rest of society wants to return to normal we can’t because, as we should, we have to continue to care for these patients,” he said.

For some, the months of long hours and hard work were an impetus to unionize. Others have found relief by getting out of the hospital and doing community service.

It remains unclear what the lasting impact of 2020 and the early months of this year will be on doctors and nurses, said Michael Weinstein, a former trauma surgeon at Jefferson University Hospitals who now works for the Philadelphia nonprofit Project HOME providing medical care and runs group sessions for doctors experiencing burnout and depression.

“This is going to affect people for quite some time, almost along the lines of a 9/11,” he said.

The burden of health care

Health care workers are at risk for anxiety, depression, and burnout in the best of times, according to a March paper that Moss coauthored in the Lancet, the British medical journal. Heavy workloads, little control over their schedules, and the weight of responsibility contribute to doctors and nurses’ burdens. Severe burnout can afflict up to 33% of critical care nurses and 45% of critical care physicians, according to the paper.

“This is something that the pandemic of course shot into a totally different level,” said Anthony Rostain, chief of Cooper University Health Care’s department of psychiatry. “We went into a crisis layered on a crisis.”

A survey from the medical publication Medical Economics released in September 2020 found that 65% of physicians polled reported feeling more burned out because of COVID-19.

Nurses tend to be open about discussing the hardships of the job and their emotional state, Weinstein said. Maureen May, president of Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals (PASNAP), noted about 10 colleagues at Temple University Hospital who organized their own wellness retreat to the Poconos.

Doctors, though, are more likely to try to white-knuckle their way through hardship.

“Especially for physicians, we’re supposed to be kind of superhuman,” Weinstein said. “In the press we’re called heroes and that can be a lot to live up to.”

The pandemic also put health care workers in unfamiliarly painful roles.

When health care systems limited visitors to keep COVID-19 from spreading through hospitals, Moss said, health care workers suddenly found themselves as proxies for family, standing by the bedside of patients in their last moments so they didn’t die alone.

Engle, the St. Mary nurse, experienced that.

The 58-year-old described an elderly man on a ventilator whose wife was allowed in the room with him because she also had COVID-19. She and Engle kept a vigil as the machines keeping him alive were turned off. The man died a few minutes later.

“Then we just sat there,” he said, and he began crying as he recalled, “she just talked about him.”

Isolation and long hours

A less obvious consequence of the pandemic for health care workers was isolation. Gone were team lunches and idle chats with colleagues. And while telemedicine received credit for allowing doctors to interact with patients without the risk of contracting the virus, several doctors said they found those interactions deflating, and at times unhelpful.

“While it’s a benefit in some circumstances, in other circumstances you wonder if you could do better if you saw the patient in person,” said Steve Permut, a family practitioner with the Temple University Health System.

Permut, who has begun seeing patients in person again, found it difficult to diagnose people virtually due to problems as simple as bad camera angles.

Weinstein, too, missed his patients. He frequently works with lower-income patients, many of whom don’t have access to a computer. Telemedicine “felt, to me, demoralizing.”

Seeing patients in person again has improved morale, he said.

The PPE shortages, long hours, and intense workloads also led health care workers to question their relationship with their employers. Greg Battaglia, a medical laboratory scientist at Taylor Hospital in Ridley Park, said efforts to unionize were already underway when the pandemic began, but the experience gave the initiative new urgency.

“It absolutely jump-started it, for sure,” he said.

He and many of his coworkers are burned out, he said, but that experience has made them push for better wages. Like health care workers across several hospitals, Battaglia said a lack of personnel contributed to long hours, with his lab logging 70- to 80-hour weeks during the pandemic.

A spokesperson from Crozer Health, which operates Taylor Hospital, said the lab is staffed adequately. The recently formed union is beginning its first contract negotiation, Battaglia said.

Engle and May both noted that their colleagues have been less quick to agree to work overtime or extended shifts.

“You can offer me all the money in the world and I’m not doing it.” Engle said. “Not anymore. I want to enjoy life.”

Rebuilding communities

Hospitals have recognized the need for mental health assistance for staff since early in the pandemic. The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania created a web service to connect workers with mental health resources. Cooper created a resiliency program.

“I think what most people want from their occupation or their place of employment is they want to feel supported and they want to feel appreciated,” Moss said.

Each person will cope differently, he said. Participation in an office softball league or finding creative outlets may help workers regain a sense of normalcy. Rebuilding community is key, Moss said, but may be harder to capture through formal support programs.

“People that you can talk to and understand what you’ve been through and kind of talk through some of the issues,” he said.

Cooper’s resiliency program includes peer support groups. Kelly Gilrain, Cooper’s director of psychological services, acknowledged that burnout may not leave people with the energy to participate in wellness initiatives.

“People are just tired of being tired,” she said.

Morgan Hutchinson, assistant medical director at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital’s emergency department, said she is energized by the vaccination effort. She has participated in Jefferson’s mobile immunization clinics, which bring doses to undervaccinated neighborhoods. Doing something to prevent COVID-19 cases, rather than treating them, is a welcomed change, she said.

“Every vaccine you give is like, so rewarding, to be able to get one more person vaccinated,” Hutchinson said. “It’s definitely helped me avoid burnout.”

Ongoing struggle

LeCoin, the Einstein nurse, loves going to the movies. Yet she still doesn’t feel comfortable, and has instead settled for home screenings with friends.

“If I go and we are distant, how do I know once the lights go down, how do I know they’re being honest and are truly vaccinated?” the 54-year-old said.

In her 33-year nursing career, she always believed that she could leave the stress at work. During the pandemic, though, the threat was everywhere. Her home no longer felt like a haven. Now she looks askance at anyone not wearing a mask, and wrestles with worries that the pandemic isn’t actually fading, but is just in a lull.

Lately, she said, she can be short tempered at work, and has felt impatient.

“I just want to sit down and eat my orange, but I can’t because I have to deal with you,” LeCoin has thought.

LeCoin is a devout Christian whose efforts during the pandemic went beyond her job. She and her husband made and distributed masks, she said.

“it was important for me to help out where I could and to do as much as I could,” she said, noting that as a Black woman she thinks about others in the Black community who haven’t had her opportunities. “This is my legacy of being a person of color.”

She is hard on herself, though, when she feels weary.

“I’m such a terrible person,” she thinks. “I’m a terrible nurse.”

But she tries to take a step back, and remember what she’s been through.

“It’ll give me a chance to just go to the bathroom, eat my orange, wash my face, just little boundaries, put boundaries on myself, as well,” LeCoin said. “It’s OK if you take that little 15-minute period away from being super-nurse and super-Christian.”