CHOP vaccine videos reach millions with special-effects wizardry, but will they persuade the hesitant?

The animations of the immune system battling the coronavirus have drawn rave reviews from the pro-science crowd.

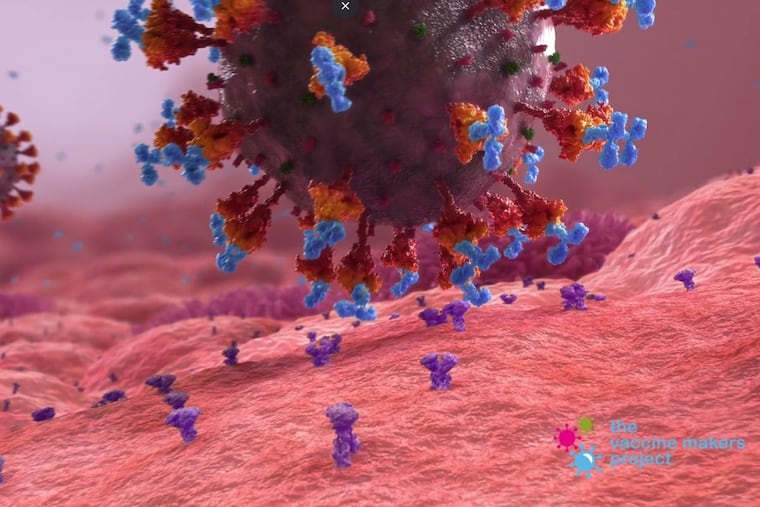

A spike-coated invader glides in for a landing on an alien landscape, poised to launch a penetrating attack. But wait — an army of three-pronged defenders swarms to the rescue, latching onto the spikes to neutralize the threat.

Say hello to your immune system and the COVID-19 vaccines, Hollywood-style.

That scene of battle is one of many dramatic moments in a pair of vaccine-education videos from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, which enlisted creative talents with expertise in the TV and film industry.

The videos, one from July, the other from October, have now been seen by millions, and they continue to reach new audiences with Pixar-like special effects. When one admiring physician tweeted the July video a few weeks ago, pronouncing it “one of the coolest things I have seen in a long time,” it drew 10.6 million views from that post alone.

But for those who still have questions or outright distrust in the vaccines, can this type of high-quality production move the needle?

Nearly a year after the first vaccine was authorized for emergency use, the key to effective public-health persuasion remains somewhat elusive. One in six U.S. adults say they will “definitely not” get a vaccine, and three in 10 parents say they will not seek vaccines for their children, according to a late-October survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

And in a recent survey of 3,050 physicians in 26 countries, conducted by Sermo, a social media network for doctors, 53% reported that their patients expressed concerns about the vaccines that have no basis in fact — such as the belief that they can cause infertility (absolutely not) or modify the recipient’s DNA (again, no).

All the more reason to keep trying, said Charlotte Moser, assistant director of CHOP’s Vaccine Education Center, which oversaw the video project. She acknowledged that some people will never be persuaded, but she is optimistic that the percentage is small.

“We’re seeking to help the people who have legitimate questions, understandably so, and trying to think about unique ways to address those questions,” she said. “We’re just really trying to find people where they are, and make sure that when they do seek information, they’re getting accurate information.”

On that score, the videos are top-notch, said Nathan Walter, a Northwestern University assistant professor of communication studies who reviewed the videos at the Inquirer’s request.

“It’s so clear,” he said. “Very vivid. The explanation is excellent.”

In addition to conveying complex science in an accessible manner, the video creators also avoided the trap of repeating any of the misinformation that they sought to combat, he said.

Yet by themselves, the videos may not be sufficient to persuade the hesitant, said Walter, whose research topics include effective health communication. A better approach might be if the videos were accompanied by personal stories and testimonials from trusted messengers, he said.

Such an approach could be incorporated within the videos themselves. Or doctors could present the videos to their patients in person, during medical appointments, he said.

Moser says that already is happening. A nurse practitioner recently called CHOP to say a colleague had shown the videos to a pregnant woman who was unsure about getting vaccinated. Upon watching the animations and hearing the endorsement from her provider, Moser said, the woman decided to go through with it.

The animations also are intended for use in the classroom, where a teacher could provide additional insight, she said.

The videos are a production of the Philadelphia-based nonprofit Medical History Pictures, which previously worked with CHOP to make an award-winning documentary about vaccine pioneer Maurice Hilleman.

To create the special-effects wizardry in the vaccine videos, the nonprofit enlisted XVIVO, a Wethersfield, Conn.-based firm that produces illustrations and animations for drug companies, government agencies, and educators.

The animations are not free-form renderings of what an artist imagines spike proteins and antibodies to look like. They are based on hard data, including images taken with scanning electron microscopes, said KC Knack, vice president and creative director at XVIVO.

The July video illustrates the science behind the COVID vaccines that consist of genetic instructions in the form of mRNA (the vaccines made by Moderna and Pfizer). Viewers see a needle delivering twisty strands of genetic code encased in protective fatty particles. The code is deposited inside the person’s cells, where it is fed through miniature assembly lines called ribosomes, resulting in the production of spike proteins.

That’s how the vaccines work: the RNA prompts the recipient’s cells to make a harmless fragment of the coronavirus, allowing the immune system to practice making customized antibodies and other defenses in the event of a real infection. Same thing in the October video — except the genetic code is delivered not with fatty particles, but with another type of virus that has been configured so it cannot cause disease. (That’s the approach used with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, among others available elsewhere in the world.)

Though realistic, the scenes of microscopic warfare had to be simplified a bit for public consumption, Knack said. In real life, human cells (and the spaces between them) are crammed with all sorts of proteins and structures that the illustrators had to leave on the cutting-room floor.

“We have to balance that with what would overcomplicate the story,” she said.

Edward Quirk, the animator for the XVIVO videos, has a background in the entertainment industry, with experience in feature films, TV shows, and motion-simulator rides. But nothing from that world can match the real-life drama of science, he said.

“It always fascinates me, the science and the incredible stuff that happens in biology in our cells,” he said. “Everyday I learn something new.”

Moser and her colleagues at CHOP hope millions of others will feel the same way.