COVID-19 is again rising fast in North Jersey, the Shore, and the Poconos

New COVID-19 cases are rising in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Even as more Americans are vaccinated and talking about post-pandemic life, new cases of COVID-19 are ticking upward in much of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as variants of the virus spread and people eager to take advantage of warm weather begin to let down their guard.

New Jersey has the highest rate of new coronavirus cases in the United States, with close to 28,000 residents testing positive in the last seven days. Traveling in a similar pattern to its early days, the virus is spreading fastest in the northern part of the state, sweeping down the shore and across the Delaware River into the Poconos.

The increase in cases was expected and is not accompanied by the alarming hospitalization and death rates of earlier surges, but doctors, researchers, and lawmakers say they are keeping a close eye on the trend.

“While we may finally have COVID on the run, the mere presence of vaccines does not mean we are out of the woods,” said New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy.

The statewide rate of transmission is 1.09, meaning each case is leading to at least one more infection. The spikes in new cases have so far been largely concentrated in the north and central part of the state, with numbers in South Jersey remaining stable. The state added 3,429 cases and 61 deaths on Tuesday.

Murphy indicated that hospitalizations and other metrics are holding steady enough that the state can proceed with plans to hold the June primary election largely in person, with voting machines.

But Murphy, who in recent weeks expanded the capacity limits for restaurants and other businesses, said he would hold off on lifting more restrictions for the time being.

“We’ve been very cautious in our reopenings,” he said this week. “That’s been for a reason.”

News that Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf plans to loosen restrictions and that vaccines are reaching more people has contributed to residents increasingly letting down their guard, said Alex Benjamin, chief infection control and prevention officer at Lehigh Valley Health Network. Warm weather and fatigue from being cooped up for so long have made easing up on the rules — just a little bit — all the more enticing.

“People are mentally relaxing, and that’s leading to more people venturing out of their homes, seeing family and friends,” Benjamin said.

» READ MORE: The Philly suburbs will get two mass vaccination sites, despite objections from ‘disappointed’ county leaders

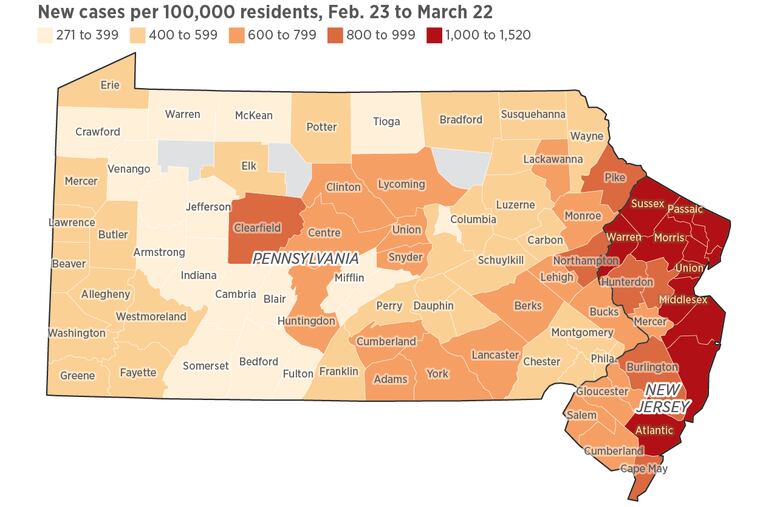

In Pennsylvania, rural central counties and the Poconos — which get significant traffic from North Jersey and New York, where rates also are spiking — have seen the most dramatic increase in cases. Over the last seven days, the number of new cases per 100,000 residents is up 45% in Pennsylvania’s northern central counties, including Clinton, Centre and Clearfield, and up 43% in the northeast. Comparatively, new cases are rising more moderately in Pennsylvania’s urban centers: they are up 28% in the Philadelphia region and 24% in the Pittsburgh area.

It’s a pattern established early in the pandemic as people from the New York metropolitan area fled to Pennsylvania seeking space and safety. Last April, Monroe County — the Poconos gateway — had Pennsylvania’s highest COVID-19 infection rate, followed by Lehigh and Luzerne Counties. The area not only is full of vacation homes and tourist attractions, it also has become something of a bedroom community for people who work east of the region.

Today, Lehigh Valley Health Network’s hospitals are nowhere near as strained by COVID-19 as they were a year ago, but Benjamin said he is concerned about the rise in cases because so many people have yet to get the vaccine. He worries that spring-break travel could worsen the trend.

“This is a very critical time for our communities,” Benjamin said. “Just hang in there. Wear your mask, consider the situations you’re going to put yourself in in the coming weeks.”

The Wolf administration on April 4 will loosen rules on outdoor events and allow restaurants to increase seating from 50% to 75% of their capacity indoors, serve alcohol without food, resume bar service, and discontinue the mandatory 11 p.m. last call. Gyms, casinos, and other entertainment venues can also increase their capacities to 75%. Additionally, indoor events may be held with 25% of maximum occupancy, up from 15%, outdoor events with 50% of a space’s capacity, up from 20%.

“Across the state, we continue to report thousands of cases a day and our statewide percent positivity rate increased this week compared to last,” state Health Department spokesperson Maggi Barton said Tuesday. “As the weather gets warm, we encourage Pennsylvanians to wear a mask, practice social distance, and wash your hands frequently as the virus still has a presence in our communities.”

Philadelphia will make only modest changes on April 4, such as allowing food to be served at indoor business meetings and allowing outdoor catered events to be attended by up to 250 people. But it will not yet adopt the sweeping changes Wolf is allowing because case counts, testing positivity rates, and hospitalizations are on the rise.

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said he is concerned the rest of the state is reopening too quickly.

“I don’t think it makes sense for us to loosen up here,” he said. “We can prevent some risk by not allowing those restrictions to open up in Philadelphia.”

Mayor Jim Kenney also defended the city’s decision to go a different direction than the state.

“When hospital admissions start going up, that’s a problem,” Kenney said. “This is Philadelphia. We’re our own county, and we have the ability and the responsibility to keep our people safe, and that’s what we think we’re doing.”

The uptick in cases comes as local health departments and health systems rush to get the vaccine to as many people as possible.

In rural Pennsylvania, public health leaders may face unique challenges in getting more people vaccinated. A study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that vaccine hesitancy is greatest in rural communities, with 35% of rural residents in a national survey of 1,676 adults saying they would “definitely not” or “probably not” get the vaccine. Comparatively, 26% of city dwellers expressed reluctance to getting vaccinated.

Half of rural survey respondents said they thought the severity of the pandemic was exaggerated by the media, while just over a quarter of urban respondents expressed a similar opinion.

That poses a unique challenge for vaccine distribution in rural areas, where health services are often limited, said Raeven Faye Chandler, director of Pennsylvania State University’s Pennsylvania Population Network, which studies demographic and health population trends.

“We have to ensure people can access [the vaccines], but we also have to ensure they want to access them,” she said.

Opinions about the severity of the pandemic and vaccine reluctance could influence how diligent people are in continuing to follow safety precautions, she said.

Public health leaders will need to build rapport with communities that are reluctant to get vaccinated to establish trust, while also emphasizing the importance of sticking with the safety rules that are still necessary.

Staff news developer Chris A. Williams and staff writers Sean Collins Walsh and Erin McCarthy contributed to this article.