How many have really been infected with coronavirus? I pricked my finger to help find out.

NIH researchers are looking for antibodies to the virus in the blood of more than 10,000 volunteers.

I elbowed my way through a crowded party in late February, hitting the buffet table, refilling my drink, and loudly talking to people up close for hours. At a bat mitzvah the next week in Philadelphia, amid growing reports of the coronavirus, I used my elbow in a different way: bumping it against other people’s to say hello.

The city confirmed its first case of COVID-19 three days later, on March 10, a Wednesday. I took the train home from work that Friday, and since then, like so many others, I have hardly gone anywhere.

Was I exposed?

I never got sick — though I felt a slight (possibly imaginary) tickle in my throat for a while — but scientists have said from the start that many people get infected without showing symptoms. How many, they still don’t know.

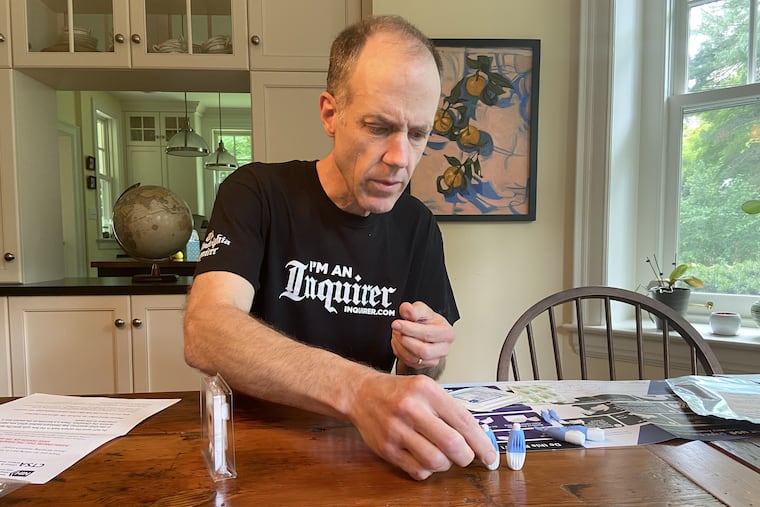

To help answer that question, I volunteered for a nationwide antibody study by the National Institutes of Health. In mid-June, a slim cardboard box arrived on my porch, containing instructions to prick my finger and ship the blood sample overnight to a government lab in Bethesda, Md. More than 10,000 other volunteers are doing the same.

The results, due in early September, will go a long way toward illustrating the scope of the pandemic — potentially answering how soon we will reach herd immunity, what percent of infected people die, and any number of other politicized questions that are best handled by science.

» READ MORE: Coronavirus antibody testing is now easy to get. But it’s hard to be sure what you’re getting.

Researchers already have conducted smaller studies of antibodies — the proteins that the immune system makes in response to infection — but some have suffered from what is called “selection bias,” said Jennifer Dowd, an associate professor of demography and population health at the University of Oxford, in England. They tested volunteers, some of whom might have signed up because they were worried they had been infected. As a result, the percentage who tested positive could have been higher than that in the general population.

Or it could cut the other way. Essential workers are likely exposed to the virus more than those who can stay home, yet they may not be aware of studies or have the resources to take part.

“These kinds of dynamics are changing over time,” Dowd said.

The true measure of the virus will come with better data. The NIH study is relying on volunteers, too, but public interest was so large — more than 400,000 people offered to give samples — that researchers say they had no problem assembling a representative sample of all demographic groups, across age, gender, race or ethnicity, and geographic location. And they made it clear up front that we would not learn our individual results, so there was no motivation for me to sign up beyond general curiosity and a desire to help.

A firm squeeze

The final number selected to send in blood samples is still in flux, but I was in a small minority, said Robert Kimberly, a professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, which is helping with the study, as is the University of Pittsburgh.

“You were very lucky to be picked,” he told me.

Or pricked.

» READ MORE: First COVID-19 vaccine tested in U.S. poised for final testing

I opened the box on June 17 and found four lancets: little spring-loaded needles that would puncture my skin with a precise click. I was only supposed to need one — the extras were in case something went wrong — and right away, I wondered if it had.

I pressed down and felt the needle pierce my skin, yet hardly any blood came out. The instructions suggested that I “massage” the pricked finger. Turned out I needed to squeeze it firmly and repeatedly to get enough blood for four swabs.

I sealed the reddened swabs in a plastic clamshell-style container, placed that inside a silvery foil bag, and immediately headed to the FedEx store to drop it off. They want the blood fresh.

Hundreds of samples have been arriving every day at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the NIH unit headed by Anthony Fauci. The kits were distributed to participants evenly over a period of three months, allowing researchers to get an idea of how fast the virus has spread during that period in various parts of the country, said study leader Matthew J. Memoli, a physician and influenza expert who studied microbiology at Thomas Jefferson University.

“We’ll know at that snapshot in time, during that three months, here’s where we were,” he said.

» READ MORE: A guide to making sense of coronavirus studies

Ensuring accuracy

Antibody testing has come under fire during the pandemic, as some of the commercial tests have been prone to inaccurate results. But even a fairly accurate test is not necessarily useful for screening individuals, said Oxford’s Dowd.

Brief math lesson: Imagine a group of 100 people, of which five actually have been infected with the virus, and let’s say we have an antibody test that correctly identifies 95% of people with antibodies and 95% of those who do not. Such a test is usually going to identify all of those five people who truly are positive (take 95% of five, and you get pretty close to five). The test also would correctly identify 95% of the 95 unexposed people as negative. But that means four or five unexposed people would be falsely identified as positive.

Among the nine or 10 people that the test would flag as positive, only five actually have antibodies. Not so helpful for an individual seeking clarity.

But antibody testing is nevertheless useful for population-level estimates. And the NIH team is going above and beyond, performing six such tests on each blood sample. They are measuring three types of antibodies that the immune system forms in response to the virus’ “spike” protein (the little knobs on the surface of each particle), and three more that are formed in response to a subsection of that spike.

The researchers first tried this battery of tests on control samples from hundreds of people, including some who were known to be infected and others who gave blood in the pre-coronavirus era. They found that if a sample came back positive on multiple tests, that indicated the person was in fact positive with close to 100% accuracy, Memoli said.

“We don’t use any one individual test alone,” he said. “We use them together to determine positivity or negativity.”

» READ MORE: Black, Hispanic women infected with coronavirus 5 times as often as whites in Philly, Penn study suggests

It’s a high-quality project that will yield valuable information, said Dowd, who is not involved in the study. But it is still not clear how well I and the other 10,000-plus volunteers will represent America, she said. The research team picked us to represent all ages, geographic regions, and race or ethnicity, and also collected information on occupation, employment status, and education. What’s more: people were included only after confirming they had not tested positive previously.

But there might be some other reason that volunteers’ virus exposure is different from those who did not sign up. A random sample would be better, Dowd said.

“It really can change the answers that you get from your data,” she said. “It’s not a technical or small issue.”

Herd immunity

Memoli agreed that a random sample would be powerful, but in the interest of speed the team went with volunteers, given the urgency of finding answers in a pandemic.

There is no question this will be among the world’s largest such projects to date, though one even larger study was done in Spain. Using a random sample of 61,000 people, scientists found that 5% of the population had antibodies to the virus, though the proportion was as high as 14% in certain hot spots.

Evidence from this and other studies suggests that among those who test positive for antibodies, at least one-third report no symptoms — though the proportion varies from population to population, Dowd said. That means if, say, 6% of people in a given area have been confirmed with COVID-19 the usual way — the nasal swabs that detect an active infection — an additional 3% have been infected at some point without realizing it.

It is not known how much of a population would need antibodies to achieve herd immunity. But even in hot spots, the exposure numbers are not there yet, said Dowd, a member of Dear Pandemic — a group of 10 women in various scientific and health disciplines who answer public questions about COVID with straightforward, plain-English social-media posts.

“We all want to get there and have some good news that things are better than we think,” Dowd said.

Short of a vaccine, we’re going to be stuck with this for a while, and it is not even clear how protective the antibodies will be against reinfection. And a reminder — don’t pay attention to the cranky Facebook poster who insists this is no worse than the flu. It is.

But hard numbers will come in September, thanks in small part to a few drops of blood from my finger.