Federal officials scramble to ensure tech glitches, bureaucracy don’t delay $1,200 coronavirus checks

The $2 trillion law signed by the president last week calls for payments to be made "as rapidly as possible."

WASHINGTON — U.S. officials are scrambling to stand up a new system to send coronavirus stimulus checks to millions of Americans, raising fresh fears that technical glitches and mismanagement could undermine a centerpiece of the Trump administration's economic-recovery effort.

The $2 trillion law signed by the president last week calls for payments to be made "as rapidly as possible," as the U.S. government looks to put much-needed cash in the hands of people who are out of work, struggling to pay their bills or in desperate need of food and other supplies in the midst of a deadly outbreak.

But the Treasury Department's ability to meet that congressional mandate hinges on systems it is still bringing online. In a matter of days, federal officials must craft a website for some people to enter their banking information, beef up their security so that malicious actors can't steal sensitive financial data, and brace to be bombarded by questions from Americans who aren't sure what they're owed and how to obtain the money.

Meanwhile, some in Silicon Valley have sought to pitch their products as a potential solution: Companies including Square and PayPal, which owns the popular app Venmo, have encouraged federal officials to use their cash-swapping services to distribute aid promptly to Americans. Two people familiar with the conversations, who requested anonymity to describe private talks, acknowledged it was unlikely the government could quickly broker such an unprecedented arrangement, which would be a boon for those businesses.

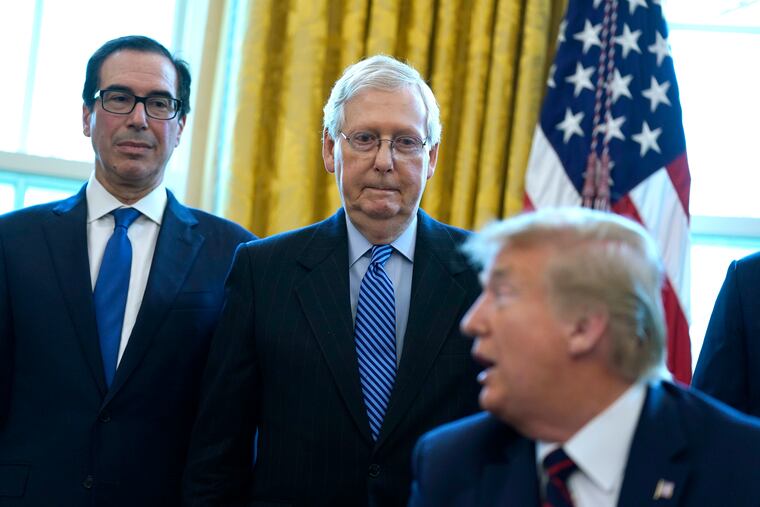

On Sunday, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin sounded an optimistic note, pledging at one point that coronavirus support would reach many Americans "within three weeks." But tight timelines — and the potential for tech troubles — suggest the payments could come out in a staggered fashion. Many Americans who already have bank account data on file with the government could receive payments quickly, but millions of others might have to wait months for the money, which can range up to $1,200 for an individual, depending on their income.

"The technology is undermining the stimulus program," said Nina Olson, the executive director of the Center for Taxpayer Rights, who previously served at the Internal Revenue Service as the U.S. taxpayer advocate.

Spokespeople for the Treasury Department and IRS did not respond to requests for comment.

The race to release $250 billion in coronavirus stimulus aid has cast a new light on a long-understood problem: The machinery of Washington often is lumbering, and in some cases, digitally deficient, complicating even the most well-intentioned attempts to provide Americans relief in an economic crisis.

Twice over the past two decades, the IRS has played a critical role in dispersing aid to workers ravaged by an economic downturn, including the 2008 recession, when the agency sent roughly $100 billion in checks to Americans. But the stakes are far more dire as the coronavirus outbreak in the United States continues to worsen, leaving more than 3,000 dead and millions suddenly jobless.

The sudden downturn threatens to thrust the country into a prolonged recession — unless federal officials can dole out the $2 trillion in new aid to businesses and consumers quickly and effectively. Exactly how and when people receive their share of federal dollars, however, will depend on a mix of still-unfolding factors.

Many Americans opt to have their tax refunds deposited directly into their bank accounts or already have shared account information with the IRS. For these families, an estimated 80% of all tax filers, the IRS can easily send them funds — no action required. But federal data show there are millions of people who have never shared such information with the government in the first place or lack bank accounts altogether. To help address this problem, the IRS said it plans to develop "a web-based portal" for people to input the necessary data.

Creating these and other systems could prove difficult for the agency, experts said. Long before coronavirus emerged as a global pandemic, the IRS's own watchdogs warned about its lack of technological prowess, telling Congress that IT deficiencies hamper the agency's ability to serve as the country's tax steward.

"The IRS's reliance on older legacy systems and aged hardware, as well as its use of outdated programming languages, pose significant risks to the IRS's ability to accomplish its mission," said J. Russell George, the Treasury Department's inspector general for Tax Administration, during an appearance on Capitol Hill in September.

Other major government tech projects, including the earliest days of its health insurance portal, HealthCare.gov, have suffered high-profile meltdowns. Adding to the challenge, federal agencies historically have been a coveted target for hackers, a security risk best illustrated when malicious actors in 2014 absconded with records on 21 million people from the Office of Personnel Management.

"We can certainly assume this website will be a target that hackers of many stripes and kinds will go after, given the amount of money being discussed here," said Tom Gann, the chief public policy officer for McAfee, a security company. He expressed optimism that the IRS would properly handle refund checks despite past "challenges."

The stimulus payments themselves are calculated based on Americans' income, as reported in either their 2018 or 2019 tax returns. Adults making up to $75,000 a year are eligible for the maximum $1,200 check, which is phased out for higher earners, and they can collect additional benefits for each child, lawmakers and regulators have promised. An estimate 150 million Americans in total may soon see such payments.

Yet millions of Americans do not file tax returns with the IRS, a category that largely includes low-income families or Social Security recipients who simply do not make much money in the first place. Under the coronavirus aid package, known as the CARES Act, the IRS has the power to turn to other agencies, including the country's Social Security office, to collect the necessary data to process stimulus checks. But the Treasury Department this week signaled it may take a different approach: It appears to require individuals to submit simple tax returns before they can receive a stimulus check.

"I think there's no question the process will be slower, potentially a lot slower, for them," said Mark Everson, the vice chairman of alliantgroup and a former IRS commissioner. He also said that the agency's budget has been curtailed in recent years, and its staff has faced the same day-to-day limitations others workers face amid coronavirus, which together threaten to add to the potential for delays.

Seeing the government's struggles — and hoping to seize on a potential business opportunity — some tech giants and financial behemoths have embarked on a lobbying blitz.

In recent days, top lobbyists for Visa have petitioned the Treasury Department to try sending some Americans prepaid debit cards as opposed to physical checks, according to two people familiar with the effort who requested anonymity to describe private talks. In Silicon Valley, meanwhile, companies including PayPal and Square asked the government to consider sending funds digitally to smartphone apps, which people could spend by using their phones or deposit to their bank accounts.

Some of the tech giants have pitched the Trump administration through lobbying groups including the Electronic Transaction Association, which publicly has written letters calling on the Trump administration to consider alternative payment options. Jack Dorsey, the chief executive of Square, tweeted last week his company hoped to help the federal government disperse stimulus dollars more expediently.

"People need help immediately," Dorsey said on the social media site, which he also runs.

Treasury officials at one point did express an openness to the idea, asking companies as recently as last week to come up with proposals for implementation, according to the two people who described the conversations. But federal aides also raised concern about how, exactly, the government could determine the real identify of a person who uses Venmo, Square or another service.

Square, PayPal and Visa declined to comment. Jodie Kelley, the leader of ETA, said companies "stand ready to help deliver stimulus money quickly and securely." Another payment app, called Zelle, confirmed in a statement it had provided "options for the government to consider in its response to the current health crisis," but declined to share specifics.

Such high-tech options were not available when the U.S. government had to mail checks to groups of Americans during the last economic recession. At the time in 2008, the IRS found itself bombarded, as it sought to manage its duties during tax season while dispensing aid to families in need, who placed an estimated 118 million calls to the agency that year just to ask questions, a federal report at the time found. Nevertheless, its checks largely went out over the ensuing months as designed.

More than 10 years later, the agency once again is serving in a lead role, managing an economic recovery program at the height of tax season. The phones again are likely to ring at record numbers, and the agency similarly has little time to prepare and even less room for error — along with sky-high expectations from White House officials and Americans coping with an unprecedented economic stall.

“People want the money already,” said Mark Mazur, the director of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center “It’s almost impossible to meet people’s expectations of when they want to get a rebate.”