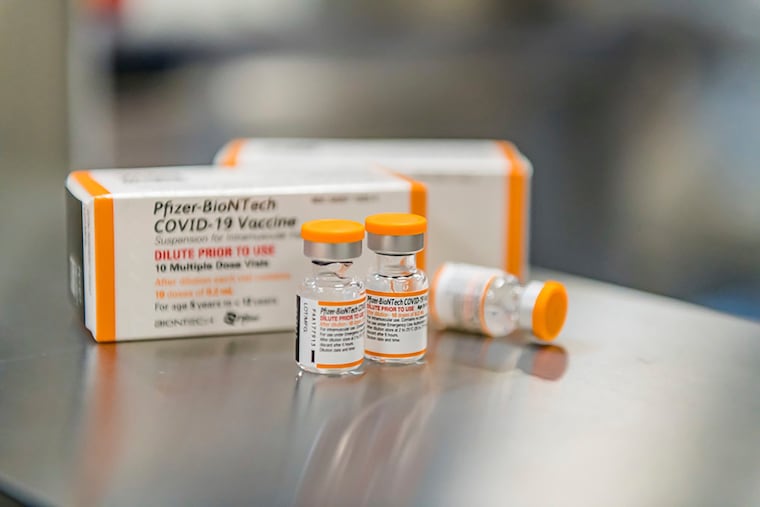

FDA review appears to pave the way for Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children ages 5 to 11

The review found that for four scenarios that were weighed, “the benefits of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine 2-dose primary series clearly outweigh the risks.”

WASHINGTON — The Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine appears poised to become available to children 5 to 11 years old within weeks, after a Food and Drug Administration review found the benefits of the shot outweigh the risks in most scenarios, with the possible exception of when there are very low levels of viral transmission.

The review found that for four scenarios that were weighed, “the benefits of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine 2-dose primary series clearly outweigh the risks.” But in one, when the virus was at its lowest levels, there could be more hospitalizations related to a rare heart side effect associated with the vaccine than because of COVID-19, the illness caused by the virus.

Even then, the review found, "the overall benefits of the vaccine may still outweigh the risks under this lowest incidence scenario" because of how hospitalized cases of the two conditions differ. The vaccine-related myocarditis cases have tended to resolve in a few days, unlike COVID-19 infections, which can lead to death.

The review represents the first independent evaluation of company data and arrives ahead of a pivotal meeting next week at which outside experts are scheduled to debate and vote on whether the vaccine should be authorized. Extending vaccine eligibility to children younger than 12 has been a major goal of public health officials and eagerly awaited by many pediatricians and families.

Pfizer and its German partner BioNTech reported in a separate document posted Friday that their coronavirus vaccine is 91% effective in 5- to 11-year-olds.

The FDA analysis of the pediatric vaccines arrived on the same day another milestone was reached in the quest to immunize Americans against a virus that has killed more than 733,000 people in the United States. Booster shots of the Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines became available for some people Friday after federal regulators this week gave their blessing to the additional doses and declared that people who are eligible for an additional shot could get any shot as a booster regardless of which vaccine they originally received.

That leaves vaccines for younger children as the last regulatory frontier in the nation’s historic vaccination campaign.

» READ MORE: Pfizer says its COVID-19 vaccines are 91% effective in kids 5-11. Here’s what else you need to know.

On Tuesday, outside experts will meet and discuss the data to inform the Food and Drug Administration's decision on one of the most momentous remaining questions for the pandemic. The authorization of a vaccine for school-aged children would open coronavirus vaccine eligibility to an estimated 28 million children in the United States and represent an important turning point in the nation's effort to control the virus.

The vaccination campaign is anticipated to launch as early as the first week of November, after the Pfizer-BioNTech shot clears key steps.

A decision by FDA regulators is expected in the days after Tuesday's advisory committee meeting. Advisers to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who recommend how vaccines should be used, are scheduled to meet Nov. 2 and 3.

The White House has drawn up a plan for distributing vaccine to pediatrician's offices, pharmacies, hospitals and other sites. Federal health officials project that in the first week, 15 million doses of the two-shot regimen will be shipped.

Vaccinations are planned to be available at more than 25,000 pediatrician and primary care offices, 100 children's hospitals and health systems, tens of thousands of pharmacies, school and community clinics, community health centers and rural health clinics. Public education campaigns will help answer questions about the vaccine.

In the company briefing document, Pfizer and BioNTech argue that authorization of a coronavirus vaccine for children in this age group "could prevent harms that include, not only interruption of education, but also hospitalization, severe illness, long-term sequelae, and death. In addition, vaccinating this population will likely reduce community transmission, including transmission to older and more medically vulnerable individuals."

Unlike older people, most children are not at high risk of severe COVID-19 infections. But at least 637 have died of the disease, according to CDC data. Pfizer's briefing document said 143 of those deaths have been within this age group and that over the first half of this year, COVID was among the 10 leading causes of death for children 5 to 14. There have been 1.8 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the age group. With the start of the school year coinciding with the dominance of the highly transmissible delta variant, about a quarter of the coronavirus infections reported in recent weeks in the United States have been in children.

"Last year, when we had lower rates of COVID in children, we kept kids at home and we refused to put them into schools, and they suffered tremendously. I'm really glad schools opened, but we are seeing high, high rates: 41 kids died last month," said Kawsar Talaat, a vaccine researcher at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who is a principal investigator for the Pfizer-BioNTech pediatric trial. "If there's a way to stop that, we should use everything we have."

Tests of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in even younger children are following close behind, and data are expected before the end of the year — first on children between 2 and 4 years old, and then on children as young as 6 months.

The vaccine regimen for 5- to 11-year-old children is two shots, each one-third the dose given to adults and teens and administered three weeks apart. There were 2,268 children originally in Pfizer’s trial, two-thirds of whom received the real shots with the rest receiving a placebo. After regulators asked the company to increase the trial size, partly to increase its safety database, the total size of the trial was doubled to about 4,500 children.

» READ MORE: CDC expands COVID-19 vaccine booster rollout for adults, OKs mixing shots

The companies reported that the vaccine triggered an immune response in participants equivalent to the one that protected teens and young adults. They also reported the vaccine was 91% effective, with 16 cases of COVID in the placebo group and three in the vaccine group. None of the cases was severe.

No cases of heart inflammation, called myocarditis, were reported in the trial. That rare side effect has been associated with the vaccine, particularly in younger males, and typically resolves after a few days.

Robert Frenck Jr., director of the Gamble Vaccine Research Center at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, said that at his hospital, many cases of myocarditis have been treated with a pain reliever.

Relatively mild side effects from the vaccine were most common after the second dose and included fatigue, muscle aches, headache, chills and fever.

The vaccine is a lower dose than the shot given to adults and is planned to be shipped in cartons with 10 vials, each containing 10 doses. It will be sent with supplies for children, including smaller needles. The vaccine can be stored for up to 10 weeks at refrigeration temperatures.

Pediatricians are anticipating a variety of responses from parents and families once the vaccine becomes available. There will probably be an initial surge in demand. But vaccine hesitancy — which has left the vaccination rate in the United States lagging many other countries — may be an even bigger issue for younger children.

Talaat said she hoped pediatricians, trusted health-care providers who have often known children since birth, would help persuade families, particularly those who are in the middle — not clamoring for a vaccine, but not opposed to one either.

"The vaccine just allows us that one extra level of safety to keep our kids in school and keep them healthy and to keep classes from shutting down," Talaat said.

The Washington Post’s Dan Keating contributed to this report.