Mandating COVID-19 vaccinations for health care workers can mean hard realities for employers

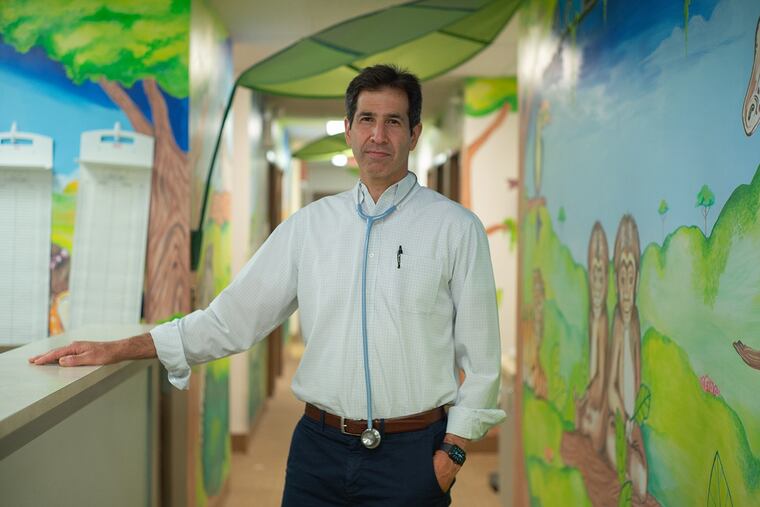

Philadelphia pediatrician Eric Berger enforced mandatory shots in May after an after-hours karaoke party caused a small outbreak among staff. Six of his 47 staff members walked out.

Christopher Richmond keeps a running tab on how many workers at the ManorCare skilled nursing facility he manages in western Pennsylvania have rolled up their sleeves for a COVID-19 vaccine.

Although residents were eager for the shots this year, he’s counted only about 3 in 4 workers vaccinated at any one time. The excuses, among its staff of roughly 100, had a familiar ring: Because COVID-19 vaccines were authorized only for emergency use, some staffers worried about safety. Convenience mattered. In winter, shots were administered at work through a federal rollout. By spring, though, workers had to sign up online through a state program — a time-sucking task.

ManorCare urges every worker to be immunized against COVID-19 but turnover has vexed that effort. Managers at ProMedica, a nonprofit health system that operates ManorCare and senior care facilities in 26 states, faced a workforce conundrum familiar to all manner of providers during the pandemic: how to persuade essential workers to get vaccinated — and in a way that didn’t drive them away. Raises and bonuses, costing millions of dollars, did not move the needle to 100%.

Animus toward the vaccine created turmoil for some providers. Dr. Eric Berger, a pediatrician in Philadelphia who opened his practice more than a dozen years ago, enforced mandatory shots in May and saw six of his 47 staff members walk out. Berger said he worked for months to educate resistant workers. In April, he learned that several, women in their 20s and 30s, had attended a private karaoke party. Within days, four staffers were infected with COVID-19.

Berger, who had seen in-office costs for protective equipment soar, then set a deadline for shots. He looks back with steely resolve over the last-minute “I quit” texts he received — and the hassle of finding a new receptionist and billing and medical assistants.

“Fortunately, we had some wonderful people who put in extra time,” he said. “It’s been stressful, but I think we did the right thing.”

Brittany Kissling, 33 and a mother of four, was one of the hesitant workers at Berger’s practice who decided — largely for financial reasons — to get vaccinated. The clinic manager couldn’t afford to lose her job. But she said she was nervous and that most of the workers who left recoiled at being told vaccinations were not negotiable. “I was a no-show my first time,” Kissling said about her first vaccine appointment. “I was scared. There were a lot of unknowns.”

But Kissling said Berger’s practice has spent “thousands and thousands and thousands of dollars” on masks and even paid workers for five days a week when they worked only two during the pandemic’s worst months. She said she understood how and why the karaoke episode prompted a mandate. “I get it from the business side,” said Kissling, about the requirement. “I do think it’s fair. I do think it is tough.”

Berger saw no other choice. “Vaccines are fundamental to our practices. That’s what we do,” he said. “Some got it in their heads that it could cause infertility; some had other reasons. It’s frustrating … [and] I don’t think it was political. If anything, most of these people are apolitical.”

At ManorCare, managers decided money could make a difference. Bonuses — up to $200 per employee — were added as an incentive, which in Pennsylvania alone cost ProMedica $3 million, said Luke Pile, vice president and general manager for ProMedica Senior Care skilled nursing centers.

According to Medicare records, the facility had 107 cases of COVID-19 among staffers and residents — and 14 deaths among residents beginning in March 2020.

Mandating vaccines is a step that ProMedica has yet to take, even as more businesses, universities and health care providers do so. A few long-term care operators, such as Atria Senior Living, operating in the United and Canada, and Juniper Communities, announced mandates. Some have been met with lawsuits from workers aligned with conservative groups. In May, more than 100 staffers at Houston Methodist Hospital filed suit to dispute and derail the hospital system’s compulsory vaccination. A judge dismissed the challenge this month on the grounds that the hospital’s requirement did not violate state or federal law or public policy. Penn Medicine also is mandating vaccines; it has received the strongest pushback from its hospital in Lancaster.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Labor Department issued a temporary emergency standard for health care workers, saying they face “grave danger” in the workplace when “less than 100 percent of the workforce is fully vaccinated.”

In Pennsylvania, whose population ranks among the oldest according to 2019 census data, statistical snapshots published in April underscored the need for vigilance. Two state agencies overseeing skilled nursing care and personal care homes reported that only half of their workers were vaccinated. COVID-19 was notably devastating to long-term care facilities nationwide in 2020; some of Pennsylvania’s deadliest outbreaks were reported by local media in places shown later to have low staff vaccination rates.

The questions and qualms about vaccines came at the end of a deeply distressing pandemic year for health care workers, and facilities are now finding fewer applicants for essential care.

By spring, ProMedica had 1,500 job postings in Pennsylvania alone, compared with a typical 400 openings. Pile said ProMedica raised wages in dozens of locations, though he declined to provide wage ranges or rates. It spent $4.5 million in Pennsylvania from March through last week — and still supplemented its workforce across the U.S. by hiring through staffing agencies.

“In 2020, we spent over $32 million on staffing agencies,” he said. Through this spring, ProMedica was on course to spend $66 million on staffing agencies for 2021, said Pile, who has worked in the care sector for 18 years.

“I have less employees than ever before,” he said. “I have never seen anything like it.”