During the pandemic, telehealth helped faraway family members attend seniors’ medical visits. Doctors want that to stay.

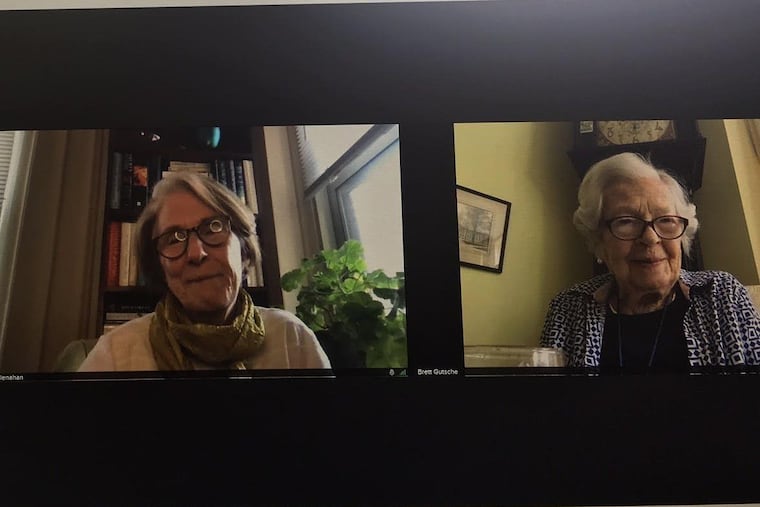

The daughter of a 90-year-old described video visits as “enormously helpful.”

Before the pandemic, Ann McClenahan would take time off from her job as a nonprofit executive director every few months and fly down from Boston to take her mother to see her Penn Medicine geriatrician, Lisa Walke, in West Philadelphia.

McClenahan has power of attorney for her mother, Barbara McClenahan, who is now 90 and lives in Dunwoody Village in Newtown Square. The older woman’s health is good, but her daughter likes to keep tabs on it.

“I want to hear what Dr. Walke is telling her, so I can support that,” she said. Plus, “I love her.”

COVID-19 brought this routine to a halt just after Barbara’s last in-person visit on Feb. 20, 2020. Since then, both McClenahans have learned to use Penn’s BlueJeans video conferencing program, so they could meet with Walke without leaving their own homes.

Barbara prefers to see Walke in the flesh, but she has no complaints. “It’s just like I was sitting beside her,” she said after a video appointment in late April.

Ann McClenahan looks forward to seeing her mother in person soon, but she, too, thinks virtual appointments that allow family members to participate from a distance have been a positive innovation. “I’d be willing to fly down three times a year to visit with her and take her in,” she said. “I’m also comfortable with the way things are going right now with continuing virtual visits.”

As COVID-19 cases drop, it’s time to consider which pandemic changes are worth keeping. Walke, who is chief of geriatric medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, thinks incorporating distant family members into geriatric care through telemedicine is one of them. “I’ve had some families who now prefer video,” she said.

Caregivers can add important information about, say, falls that patients may try to downplay. Walke thinks it’s important to see patients in person at least once a year. “There’s no substitute for my being able to listen to your heart or being able to look into your ears and eyes,” she said. But some families may find that a combination of in-person and telehealth visits works best for them. Patients could also go to the doctor’s office and family members could join virtually.

While some patients lack internet access — another disparity the pandemic has highlighted — Walke said telemedicine has improved communication for some families. “All of us believe video visits are not going to go away,” she said.

It is not known whether insurance companies, which expanded coverage for virtual visits during the pandemic, will continue paying for them, but doctors are hopeful that they will.

Bill Hanson, chief medical information officer for Penn Medicine, said Penn was holding 300 to 500 telehealth visits a month before the pandemic. After the virus struck, there were 8,000 virtual visits a day.

Many people have returned to office visits, but Hanson, a cardiac anesthesiologist and intensivist, said both doctors and patients are now much more comfortable with technology. “It’s in the ecosystem,” he said. “It’s in the work flow.”

During rounds in an intensive-care unit, he met a patient who was in the midst of a video call with his wife. Hanson introduced himself to her and she listened to the encounter with her husband. “That’s all in play now,” he said.

» READ MORE: Doctors offer advice for how to prepare for your telehealth visit | Expert Opinion

From translation to end-of-life care

Virtual meetings can allow remote translators to work with patients. They allow extended families to discuss big decisions involving critically ill patients with the care team. They can let a cancer patient at Lancaster General Hospital discuss a bone marrow transplant with a Penn specialist in West Philadelphia. Hanson knows a son in Montana who virtually joined an in-person meeting between his mother and her doctor about risky heart-valve surgery. These sorts of virtual care are likely to survive the pandemic, Hanson said.

Andrea Schwartz, a geriatrician who is medical director of the geriatrics clinic at VA Boston Healthcare System and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, said telemedicine has had an “outsized” impact on older patients. At the worst of the pandemic, it protected the most vulnerable demographic group from disease, but it also showed doctors the advantages of virtually meeting patients and caregivers where they live.

In 2015, the VA created a telemedicine program meant to help rural veterans access care, Schwartz said. Patients could go to a local VA office, where vital signs would be taken. They would log on to computers there and talk to specialists in her office about more complex aspects of their care. It meant caregivers could take off half a day for a visit instead of a whole day that involved lengthy travel.

Everything went virtual when the virus started circulating, and a surprising thing happened. “Our no-show rate in the clinic plummeted,” Schwartz said. She could still see patients who didn’t feel up to traveling. Finding transportation was no longer an issue.

Like Walke, Schwartz has included remote family members in visits, but doesn’t know how common that has become among geriatricians. “I hope it’s a trend that will continue, because I think it really benefits patients to have their loved ones involved, if they want them to be,” she said.

Susan Parks, a geriatrician who is medical director of Jefferson Health’s Center for Healthy Aging in Center City, has found telemedicine especially helpful for caregivers of patients with dementia, a group for whom “getting to the office was such a huge challenge.” Sometimes adult children have gone to a parent’s home for virtual visits.

John Liantonio, director of the palliative care team at Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience and Methodist Hospital-Jefferson Health, said virtual visits have allowed medical teams and large families to get together to discuss extremely sick patients more quickly. Before, he said, he was often “cold-calling families with terrible news.” Now, he said, the internet has “given people an opportunity to look you in the eye.”

He thinks telehealth will be especially useful in the future for advance care planning. It’s hard to get patients to make office visits to discuss their end-of-life priorities. Liantonio finds they’re much more relaxed when they can sit at home on their couch — and they’re a lot more likely to show up.

Doctors have been surprised by how well some of their oldest patients have taken to virtual visits. “Our ability to connect with folks via telemedicine was way higher than I think anyone anticipated,” Parks said.

Schwartz said the VA addressed inequities by sending some patients tablets, teaching them to use them, and coaching them through a mock visit. Penn has worked with Generations on Line, a Philadelphia organization led by Tobey Dichter that helps older adults learn to use computers. It created an online tutorial called easytelemedhelp.org to help seniors navigate BlueJeans. The group uses big type and avoids jargon. One of the sticking points, Dichter said, was that older adults didn’t know where the computer camera was.

» READ MORE: How COVID-19 could lead to the rapid adoption of telehealth | Opinion

‘I think they’re wonderful’

Barbara McClenahan didn’t bother with the tutorial. She learned to use a GrandPad, a simple tablet, to talk with her family during the pandemic. “It has opened a whole new world to me,” she said. But, for her visits with Walke, a Dunwoody employee brings her a laptop and helps her join the conference.

Her most recent visit was upbeat and sociable. She told Walke she was seeing a neurologist because her feet hurt. She could still hear a pin drop, but needed new glasses. “My eyes have changed significantly,” she said. “I have a great deal of trouble reading the New York Times now.”

She said she was eating well. Ann McClenahan asked her mother whether she was eating “healthy.” The older woman confessed to munching a couple Heath bars a day. Ann covered her eyes. Barbara lifted the glass of tomato juice she was drinking, but said the day’s sandwich had been too dry, so lunch was juice and cookies. She was worried that she had lost her wallet. Her daughter said she would help. Barbara told Walke her mood was good.

They broke away for a discussion she deemed too private for a reporter. “I’m comfortable to tell her almost anything on my mind,” she said later of Walke. She praised her doctor for helping her give up sleeping medication she started taking when her late husband had Parkinson’s disease. “I sleep like a lamb,” she said.

She does not think it essential that her daughter attend her doctors’ appointments. She’s been taking care of herself since she was widowed at 64. She used to go with her own mother, though, and says it’s nice to have Ann with her. “It’s not a necessary thing, but it’s comfortable to have her there.”

Ann McClenahan said she and Walke often talk briefly after the video visits. “I just find that enormously helpful, and it just makes me emotionally feel better, like I know what’s going on,” she said.

Her mother, a social woman who has missed seeing her friends, gets a kick out of the video appointments. “I think they’re wonderful, don’t you?” she said. “We all were laughing and joking, but we also got some things done.”