The clues are in the poop: COVID-19 sewage testing is coming to Philly

Philly was early to testing wastewater, but the program ended and the city has fallen behind.

While COVID-19 cases in Philadelphia are rising to the point that the city will reimpose a mask mandate, a different metric heralded the uptick a few weeks earlier in other parts of the country. The clues were in poop.

For months, the city’s public health department has been trying to set up a wastewater surveillance system as an early warning signal for coronavirus outbreaks. As home testing becomes more popular and diagnostic testing less accessible to the uninsured, wastewater numbers are an important supplement to increasingly imperfect testing data.

Philadelphia was early on the scene with a pilot program in May 2020, but the city has gone about a year since that initiative ended without studying its wastewater, even as the technique became more popular. It hopes to restart the program in a few weeks.

In September 2020, the CDC launched a National Wastewater Surveillance System, which has set up testing sites in 44 different states across the U.S. At least 13 counties in Pennsylvania, including Chester and Montgomery, are currently monitoring COVID levels in wastewater, and the state health department is setting up a statewide program using $4 million in CDC funding.

» READ MORE: Philly looks for signs of COVID-19 in its raw sewage

Philadelphia has fallen behind, but “this game is a long way from being over,” said Howard Nadworny, an infectious disease doctor who heads Erie County’s wastewater surveillance system, which was set up in 2020.

“We are at great risk in public health of getting more blind” to the state of the pandemic, Nadworny said, “maybe even similar to what happened in the beginning of 2020.”

COVID data can be slow and inaccurate, and it’s only getting worse. Wastewater can help.

Wastewater testing can be a canary in the coal mine for COVID because it doesn’t rely on testing people, which may only happen after known exposures or the onset of symptoms.

The “lead time depends on the delay in reported cases,” said Scott Olesen, a researcher at Biobot, a private wastewater testing company. Wastewater monitoring can be particularly helpful during surges, when health departments can be overwhelmed by the volume of tests.

When Philly ran its 12-month pilot program in 2020 and 2021, “we did find signals in the data, and they were nice signals. They tended to precede the case data by about three days. But not always,” said José Lojo, an epidemiologist at the city’s public health department. In other cases, the wastewater data was “coincident with the testing data, and so it appears to be a nice adjunct.”

Wastewater data has also been a good predictor of hospital admissions, which lag cases because it takes time for infections to become severe enough to warrant hospitalization. Some health systems have looked to wastewater data to help manage hospital capacity, such as deciding whether to schedule elective surgeries.

Wastewater data isn’t just an earlier indicator — it could also be a more comprehensive one. Recent research has shown that wastewater has the potential to help estimate the “true” number of cases in a community.

Wastewater sampling, if done hyperlocally, can also be a way to monitor specific populations without subjecting them to routine testing.

When the University of Pennsylvania ran a pilot wastewater program last year, it sampled from dormitory sewers and libraries. At the time, the university also tested students twice a week. That data aligned closely with results from wastewater testing, showing that wastewater data could track disease spread, said Jennifer Pinto Martin, an epidemiologist at Penn’s School of Nursing. Penn no longer requires constant testing of students, so the university is considering whether to bring back wastewater testing.

In practice, wastewater testing comes with its own challenges. For one, the extent to which monitoring can serve as an early warning system depends on which variants are circulating, said Jordan Peccia, a Yale University engineering professor who has been studying wastewater. “With omicron, you’re usually in the hospital pretty quickly,” he said, which shortens the lead time that wastewater offers.

Researchers also don’t know how much viral matter a person sheds, or for how long.

“We have two confounding factors: One is that these variants impact people differently and they likely shed differently,” Peccia said. “And No. 2 is, depending on your vaccination status … you respond to the infection differently.”

Peccia has gotten around the problem by studying concentrations over time together with other testing data.

The CDC emphasizes trends in concentrations on its wastewater dashboard, as opposed to the concentrations themselves, in part because different sites may have different sampling methodologies making it difficult to compare numbers. Natural phenomena like rainfall can also affect readings.

The CDC is still figuring out how best to convert viral wastewater concentrations into estimates of the number of people infected with COVID, Lojo said, which could correct undercounts in the reported case numbers.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” he said.

Philly was early on the COVID-19 wastewater scene. Now it’s behind.

Philadelphia first started testing wastewater in May 2020, just two months after the city’s first reported case. Over the next year, as part of a $140,000 pilot program, the Philadelphia Water Department each week sampled wastewater from three sewage treatment plants that handle all the wastewater the city produces.

Then Heather Murphy’s lab at Temple University took over.

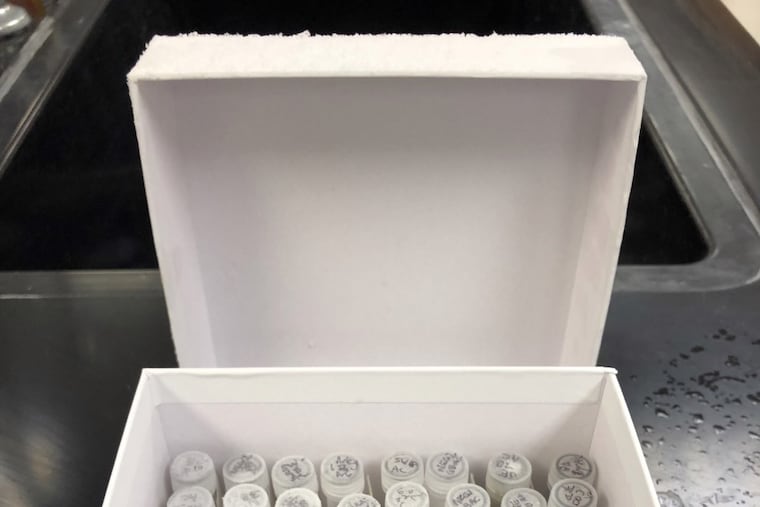

“We essentially take 100 milliliters of wastewater and concentrate it down into a pellet that we then analyze for the virus,” said Murphy, an epidemiology professor.

Murphy shipped the pellets to Michigan State University, where they were analyzed. Researchers also did “preliminary work” to identify the presence of specific variants, Murphy said.

After the pilot program ended and the city stopped wastewater testing, Philadelphia was hit with the delta and omicron waves, both of which other jurisdictions detected early in wastewater. Unable to test wastewater in real time, the city has been freezing samples since this January to better understand the omicron surge — retroactively.

Philadelphia was awarded funding last August to restart surveillance and join the CDC’s national program. It took almost seven months before the city signed a $700,000 contract with Temple, two weeks ago, to conduct wastewater testing through July. That will likely be extended by three to six months.

“It’s unfortunate that it’s taken so long,” Lojo said.

The city described the delay as a routine part of contracting. A new city law requiring disclosure on the diversity of recipients of city contracts added to the delay, said health department spokesperson James Garrow.

Sample testing is expected to resume soon once Temple finalizes a subcontract with Michigan State. The lab expects to start producing real-time data in a few weeks.

How Philly’s new wastewater testing will work — and how it can help make health policy

The city now wants to go beyond measuring overall virus levels and known variants by sequencing viral particles to identify entirely new variants. Cities that have taken this step, such as New York, have discovered variants that previously went undetected.

Philadelphia plans to sample from each of the three wastewater sites twice a week, doubling its collection. Some readings can’t detect COVID because of how they’re taken. It’s not necessarily because there really is no virus in a sample, but because “environmental conditions” can affect the minimum level of virus needed to be measurable, Lojo said: “Some days, the water is crystal clear. But say, after a rain on other days, the water … is cloudier.”

“Increasing the number of samples a week should help us with respect to not only figuring out if we actually have signals, but also establishing better trend lines,” Lojo said.

The city could also collect samples from more locations, getting a more detailed picture of COVID levels across different neighborhoods. That kind of hyperlocal data could, for example, help direct testing resources. Only people who actually know they’re sick in the first place can isolate and prevent spreading COVID further, so testing wastewater doesn’t replace testing people. Instead, wastewater data can help officials understand where to focus their efforts. For instance, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections studies wastewater to help determine how to more effectively deploy testing in state prisons.

City officials have discussed improving the geographic granularity by sampling from more sites.

“There are some ideas trying to figure out how best to go upstream” to sample wastewater in city sewers, Lojo said. “It’s not clear if we’ll have enough money to be able to expand it, unfortunately.”

Philadelphia could also incorporate the wastewater data into its weekly COVID alert system, but it doesn’t currently have plans to do so, partly because the wastewater treatment plants also serve some of the suburbs. “There’s no real good way to adjust for that in the analysis,” Lojo said.

But the city isn’t ruling out the possibility of using wastewater data to determine COVID restrictions in the future, Garrow said.

About the data

Wastewater sampling data were sourced from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health through a records request. The data for July 1, 2020 are excluded because the department identified it as an unexplained outlier that is not thought to be a lab error.

Hospitalization data are published by the state Department of Health. They include probable and confirmed cases of COVID-19 identified in a Philadelphia hospital setting.